Stephen Gold: I complained to Tesco about a wrongly priced non-organic cucumber worth 45p – and got a £5 voucher

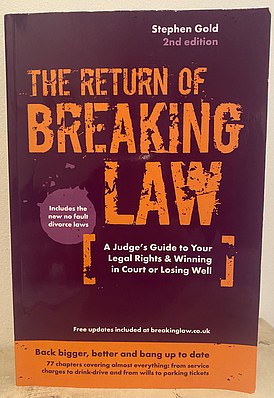

Stephen Gold is a retired evaluate and author who has written popular series for This is Money on how to be a successful executor, writing a will and bankruptcy.

In a new three-part guide, he is going to give This is Money readers a hand with their Christmas shopping as December rolls around.

Today, find out your rights on pricing errors, credit and debit cards – and what happens if your carrier bag breaks.

It’s that time of year when you come just that bit closer to falling out with the shop manager.

Hopefully, not with the spouse or civil partner, down to excessive yuletide exposure, as the court fee for bringing a divorce or partnership dissolution case looks admire rising by 20 per cent to £652 around March next year.

First, let’s look at your rights when you’re buying gifts this Christmas.

‘I demand that for a penny’

You cannot compel a shop to sell to you. In legal eyes, when it displays goods, it is inviting you to offer to buy them.

You make the offer when turning up at the till and the assistant decides whether to adopt it.

If you are wearing coloured flared corduroys – corduroys which I am going to unveil you to later, if you stick around – probably not.

Similarly, where the goods have been displayed with a £10 ticket when they would be charged for at £100, you cannot force a sale at the lower price.

What you can do, however, is to remind the shop of the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 which make it an offence for a trader to mislead a customer or potential customer about the price of goods available for purchase.

In order to avoid a conviction, the trader would have to show that the misleading was down to a mistake, accident or another cause beyond their control and that they took all reasonable precautions and exercised all due diligence to avoid an offence. Not an easy task.

A few years ago, I bought two cucumbers from Tesco Metro, as one does. An organic cucumber at £1 and a non-organic cucumber at 45p.

I was charged the organic price for both and wrote in to complain, as one does. I said I was too busy to return to the store.

They came back promptly asking for copies of both my till receipt and cucumber labels.

I obliged and accepted they needed to protect themselves against what could have been an attempt at obtaining 55p by deception.

I stated that if they wished to send the branch manager to my home to authenticate the copy documents against the originals, I would be happy to see him by appointment and perhaps he might care to partake of some organic cucumber sandwiches while he was with me.

I was issued with a Tesco Moneycard for a fiver ‘so that you can make some extra sandwiches.’ Sublime.

Plastic stories

You probably know as much about section 75 of the Consumer Credit Act 1974 as your pet’s dietary requirements. Or do you?

That’s the law which applies when you buy with a credit card and the price of the item is over £100.

It makes the credit card company equally responsible with the seller for most of their sins such as selling you duff goods or spinning you porky pies about what they can and cannot do.

Handy when goods fall to pieces and the shop goes down the drain or won’t play nice.

And the company is not just equally responsible for refunding the price or paying you compensation for the diminution in their value but for consequential losses.

Back to my life story again, I’m afraid. I once ordered a new desk through a newspaper ad (not The Mail, of course) and paid for it with my Barclaycard.

Desk never arrived. Trader collapsed. I took advantage of section 75 and claimed from Barclaycard the price paid for the desk which had been a very good deal.

In addition, I claimed the difference between that price and what I was going to have to pay elsewhere for a comparable desk.

The difference was around £200. Barclaycard baulked at the extra claim but eventually caved in and settled the lot. Quite right as section 75 meant they were liable for consequential as well as direct loss. I am typing this on the replacement desk right now.

You cannot get around the plus-£100 threshold by buying a selection of items which are individually priced at under £100 but together add up to over £100.

But section 75 will apply where you have paid with a mixture of credit card and cash or cheque.

If the price was £101 and you paid £1 on the card and £100 in cash, the credit card company’s liability to you would be exactly the same as where the entire £101 had gone on the card.

It will also apply although the purchase took you over your credit limit or you are in arrears with payments to the credit card company.

Alas, there is one Great Big Party Spoiler of which to beware. If another company comes into the picture – an intermediary – and is involved in processing payments, admire PayPal or Amazon Marketplace, section 75 will not help.

Should you make a section 75 claim, and the credit card company reckon it is off the hook because of the Spoiler, it will be quick enough to say so.

But its assertion can always be tested with a complaint to the Financial Ombudsman’s Service which is well used to deciding this issue.

Nevertheless, the intermediary may have a buyer protection scheme which will make up for loss of section 75 rights, but it will usually be inferior to them.

It’s Chinese to me

Take the PayPal scheme whose rules allow them to necessitate any action they specify in connection with a dispute and make a final decision against a non-compliant party.

In a 2020 High Court case, the buyer was after money back for a defective laser machine supplied by a Chinese seller.

PayPal directed the buyer to return the machine to an address it provided which was mainly in Chinese script.

The buyer contacted the seller direct, and they provided an address in Latin script to which the buyer returned it. But it came back.

PayPal contended that the buyer was in breach of its direction about the address to be used and so he was not entitled to a refund under its scheme.

The court ruled that Chinese script was not within the buyer’s competence and performance of PayPal’s requirement was impossible and unreasonable. PayPal had to pay up.

Debit card alternative

Should you pay by debit card, section 75 will not bite. If you use both credit and debit, it can do.

However, with no section 75 but use of a debit card, there is another regime that usually kicks in.

It’s called chargeback, under which the card issuer may organise a claw back of the price of defective goods from the seller’s account.

You normally have around 120 days from when the transaction shows up on your card account to inquire the issuer to swoop into action and, if they refuse, you can put in a complaint to the Financial Services Ombudsman.

Not as good as section 75 and no indirect or consequential losses will be paid over.

Everything packed?

Take a sturdy bag with you, especially if planning to buy two dozen tins of pilchards. That’s because the shop supplied bag may not be up to scratch as it legally should be.

A couple of years back, a supermarket cashier plonked a bottle of wine into one of the store’s plastic bags for me. As I left the store, the bag exploded, and the bottle rolled onto the pavement.

Its passage was brought to a summary end by a kindly Big Issue vendor who, I am ashamed to say, I had not patronised on my way in.

Bags and packaging supplied by the seller, admire the goods themselves, should be reasonably fit for their purpose and of a satisfactory standard. Otherwise, the seller will be responsible for your losses.

IN PART TWO… Stephen Gold explains how to return faulty or unwanted goods and get your money back.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money, and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to inspire products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.