honglouwawa

For thousands of years, civilization has benefited from some form of globalization. Historians may point to the establishment of the Silk Road in the 2nd century B.C.E. as the true initiation of trade from one region of the world to another.

But advancements in transportation, freedom of the seas, and global growth have driven demand for more diverse goods, often at considerably lower costs, and geographic diversification from a manufacturing risk-mitigation perspective. It has been a win-win for both consumers and commercial establishments. What could possibly go wrong?

Behind the Globalization Backlash

In recent years, globalization has begun to slow down slightly, as supply chain disruptions, many of which started well before COVID-19, collided with an ever more demanding manufacturing and retail base that expected just-in-time (JIT) deliveries.

JIT is a supply chain strategy focused on minimal waste and maximum efficiency to reduce costs while satisfying immediate customer demands. Suppliers may be given a “delivery window” to confront, as well as an explicit volume of goods that are expected to be delivered. If either the time or the volume varies from the order placed, the supplier could be penalized.

With logistics and systems tracking commercial activity on a real-time basis, JIT can work for manufacturers, retailers, and suppliers. All are faced with inventory carrying costs that encourage lowering safety stock if JIT works as planned.

encourage, there are many reasons why supply chains began to stumble despite advanced technology throughout the process. A few of the more important disruptive variables might include geopolitical tensions, tariffs, transportation and labor costs, intellectual property (IP) security, and incremental U.S. government financial incentives.

At the same time, U.S. manufacturers utilized enhanced productivity, embracing automation, robotics, software, and most recently, artificial intelligence (AI), to narrow the cost differential with lower-cost regions of the world. Terms appreciate “friend-shoring” and “near-shoring” have also gained traction, but our focus will be on those companies transferring goods, components, materials, sub-assemblies, or IP back to the United States – specifically, a term we will refer to as “onshoring.”

In sum, providing products on time, on budget, and on spec is driving suppliers and retailers at every level to rethink their production and sourcing outside the United States, which is a shift that has the potential to benefit U.S. small- and mid-cap companies.

Onshoring Today

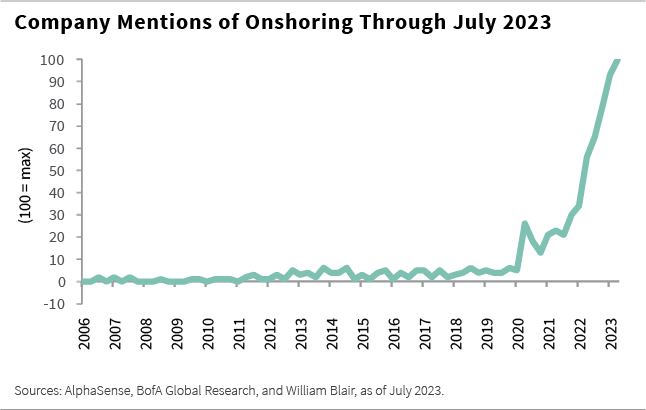

The chart below highlights U.S. companies that are formally using the term “onshoring” in their public filings. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that the concept gained traction because of COVID-19, but note that onshoring began well before the pandemic and has accelerated exponentially since then.

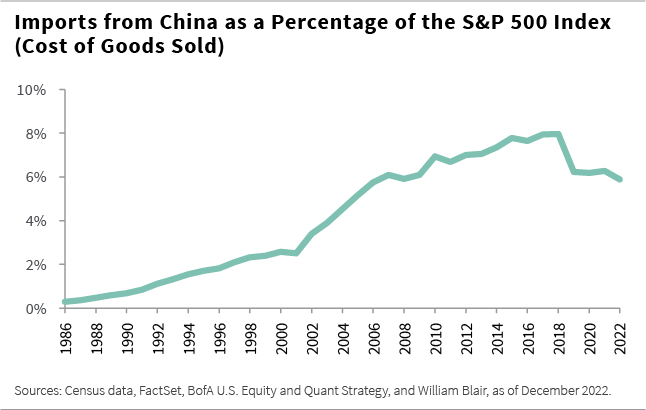

While the popularity of onshoring has grown, the opposite is true for some developing markets such as China, whose exports to the United States have slowed since 2017. Note too that the chart below only extends through 2022, but we expect that we likely will not see a reversal of this downward trend in 2023.

Numerous delays or cancellations of new U.S. investments into China, intensified Chinese regulatory scrutiny (concerning data access, personal information, and cyber security), and rising nationalism within China in recent years have exacerbated this exodus.

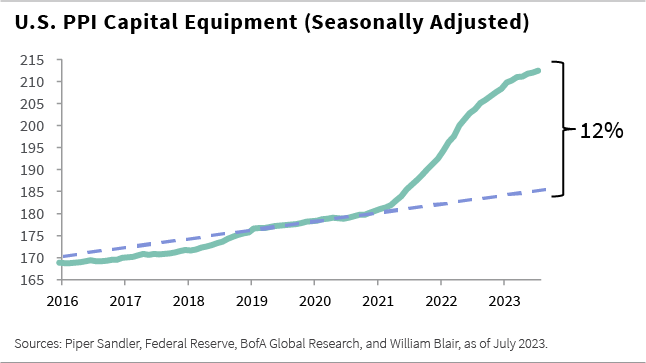

For U.S. onshoring to occur, we will likely need to see U.S. capital spending – and specifically, construction spending – to expedite. It is particularly impressive to witness this pick-up in producer spending, shown in the chart below, considering that interest rates have been on the rise for the past two years.

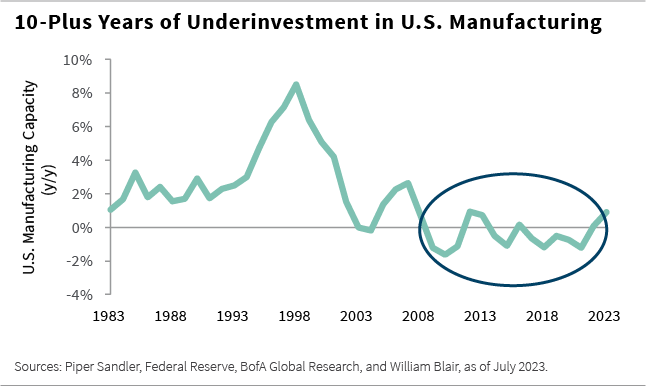

When observed over a longer period, what should be apparent is the underinvestment seen in U.S. manufacturing since the Global Financial Crisis, which accentuates the more recent spending required, as shown in the chart below.

Onshoring: Cyclical or Secular?

In addressing the duration of onshoring, it is important to ask three key questions about supply chains: are they cost-effective, do they mitigate risk, and what is the level of confidence and trust in their reliability and sustainability.

We have pointed out that U.S. technological and productivity improvements continue to evolve, often narrowing the previous cost advantages of developing or emerging economies while labor costs abroad have often materially risen.

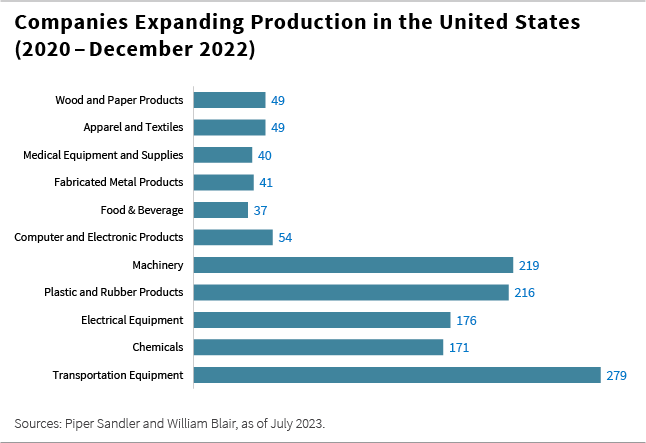

The breadth of industries undertaking onshoring initiatives is impressive, as shown in the chart below.

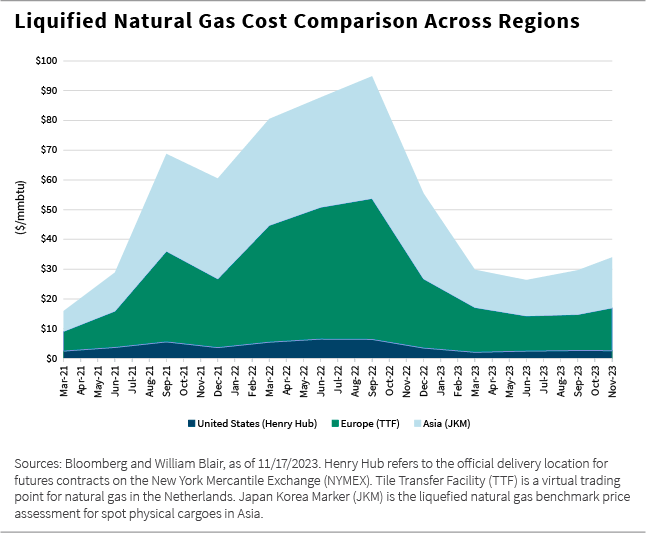

What too often is overlooked by investors in our opinion is the enormous cost advantage that the United States holds from an energy perspective. As the chart below demonstrates, U.S. manufacturers that rely on natural gas as an input cost are structurally advantaged in comparison to foreign competitors. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, this energy cost advantage has encourage increased even after the initial energy price spikes in Europe and Asia have subsided. As of the time of this writing, U.S. companies are only paying $2.50 to $3.00 per 1 million British thermal units (MMBtu), while their peers in Europe and Asia are paying $14 to $16 per MMBtu.

Recent U.S. legislation creating incentives and subsidies for strategic industries has proven to be a encourage accelerant to onshoring, including the CHIPS and Science Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the Defense Production Act. While the Fed’s actions to raise interest rates and tighten lending will undoubtedly pressure economic growth, slow capital spending, and thus onshoring generally in the short run, we believe the secular trend of onshoring is indisputable.

The Impact of Onshoring on U.S.-Centric or Local Companies

While the media and Wall Street have largely ignored the benefits of onshoring beyond the companies transitioning, the reality is that capital spending on the factories being built represents a fraction of the total spend when considering the surrounding infrastructure that is often required. Roads and services – both public and private – may meaningfully create or extend communities.

We believe local companies are likely to disproportionately benefit because of their flexibility to adjust and answer quickly. This is a distinctive tailwind for small and midsize companies that we expect will play out over many years.

One mid-cap quality U.S. company that we expect to benefit from onshoring is a leader in rock quarries. While it may seem appreciate a commodity business, this company deals in aggregates such as rocks, sand, and gravel. These materials are expensive to transport given their weight, and thus local oligopolies are created around these quarries. Whether it is roads, bridges, or concrete production that is required, only those geographically close to the customer are likely able to price competitively.

Another potential U.S. onshoring beneficiary is a leader in the production and distribution of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) pipe, which is used in stormwater and sanitary sewer applications and offers several advantages over traditional concrete piping. Because HDPE pipe is lighter, easier to install, and erosion-resistant relative to concrete, this company appears poised to savor a significant tailwind as capital spending continues to ramp up.

In Conclusion

As onshoring continues to reshape the global trade landscape, it is crucial for investors to grasp its impact. We believe our focus on bottom-up investing allows us to better appreciate the secular trends impacting U.S. companies while identifying those that may specifically benefit from onshoring, as described above, providing us with a longer-term investment edge.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.