tadamichi

One of the issues of an interest rate focussed blog is that bond markets can settle into rather uneventful extended range trading dynamics. This has been the case for U.S. inflation-linked bonds, at least from a strategic perspective. That is, given a target fixed income allocation (which depends upon preferences and situation of the investors involved), should we hold inflation-linked or conventional government bonds?

(The general tendency is to overweight bonds that incorporate credit or prepayment risk, making the allocation decision slightly more complicated. This is because there are no large sources of private sector inflation-linked bonds. This means that even if we think inflation-linked bonds (also known as “linkers”) will mildly outperform conventional government bonds, “spread product” might still outperform them. To make life simple, I am just discussing the credit risk free investment space.)

(I assume that the reader is familiar with the definition of a breakeven inflation rate. To quickly recap, it is the future average rate of inflation that results in an inflation-linked bond and a conventional bond of the same maturity having the same total return to maturity. If that is not enough information, it is explained in this primer on my blog, and at more length in my rather amazing book on the inflation linked market.)

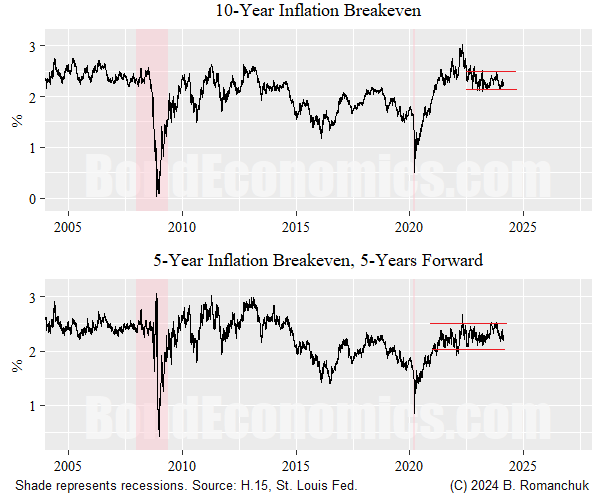

If we look at the figure at the top of the article, we see that the 10-year breakeven (top panel) has settled into a trading range after a certain amount of excitement around the pandemic. The 5-year breakeven rate, 5 years forward — which isolates the breakeven from near run expected inflation from energy markets — settled into a similar range even earlier.

If we are doing leveraged relative value trading, there certainly were opportunities to make or lose money trading linkers. However, from the strategic standpoint, we are interested in chunky out-/under-performance of the overall asset class versus conventional bonds, and we need a lot of carry or breakeven movements for that to happen. From the perspective of a long-term investor, this is not a disaster, as you might want a partial hedge against large movements in expected inflation. (Note that this hedge has limitations.) You probably want to allocate your risk budget elsewhere — and you might have gotten better returns.

One way that this could be interpreted is that central bankers are doing a great job of anchoring inflation. Yay! Another theory is that modern economies have a lot more inflation inertia than they did during the peak of the welfare state and Old Keynesian business cycle management. Yet another theory is that the linker market is broken, and/or fixed income investors are delusional.

Anyone familiar with modern quantitative research will start to ask questions about the risk premia embedded in the breakeven inflation rate. My bias is that outside a crisis, linkers tend to be slightly expensive to fair value since the ultimate source of inflation protection is only central government linker supply. (Other issuance is invariably swapped by somebody, and the inflation swaps market in turn relies upon government linkers for inflation protection. All the investors with big balance sheets are already short inflation risk, and no counterparty in their right mind is going to accept large amounts of directional inflation risk from fast money accounts with flimsy balance sheets.) The beauty of my theory is that it is largely non-falsifiable in the absence of another century of data, so I will not worry about alternative theories here.

This theory is telling us that bond investors expect that the next decade will probably resemble the bulk of the post-1990 experience and stick around 2% or so. In other words, the mood swings regarding inflation among the economics commentariat had almost zero pass through into breakeven inflation pricing.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.