Gregg Martin, author of ‘Bipolar General,’ at his home in Cocoa Beach, Fla.

Michelle Bruzzese for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Michelle Bruzzese for NPR

Gregg Martin, author of ‘Bipolar General,’ at his home in Cocoa Beach, Fla.

Michelle Bruzzese for NPR

One of the biggest problems for Maj. Gen. Gregg Martin was that bipolar disorder seemed to help him at first.

“I was manic most of the year in Iraq … felt like Superman. Bulletproof, pretty much fearless all over the battlefield,” Martin said.

He deployed to Iraq in 2003 as a colonel, in charge of the 130th Engineer Brigade that paved the way to Baghdad from Kuwait. He led from the front, aggressively, pushing his troops with relentless positivity. In his downtime he favored intense workouts over sleep. His mania fit right in with the American military mystique. His superiors gave him almost nothing but praise.

“I thought that God was rewarding me and giving me this strength and motivation and energy, because I was on kind of a divine mission as an Army officer. So it never occurred to me that there’s something wrong with my brain,” he said.

Then the pendulum swung. His Iraq tour ended in 2004 and Martin went home despondent. At a post-deployment health screening he spoke openly about depression. The nurse asked him what he did to cope.

“I said, ‘Well, I do lots of really intense physical activity, even though it’s hard to do because I’m depressed. I listen to really intense rock-and-roll music. I repeat power verses from the Bible and when that doesn’t work I drink. I drink a lot, way more than I ever have in my life,’ ” said Martin. “And they said, you’re fine, there’s nothing wrong with you.”

Military mindset

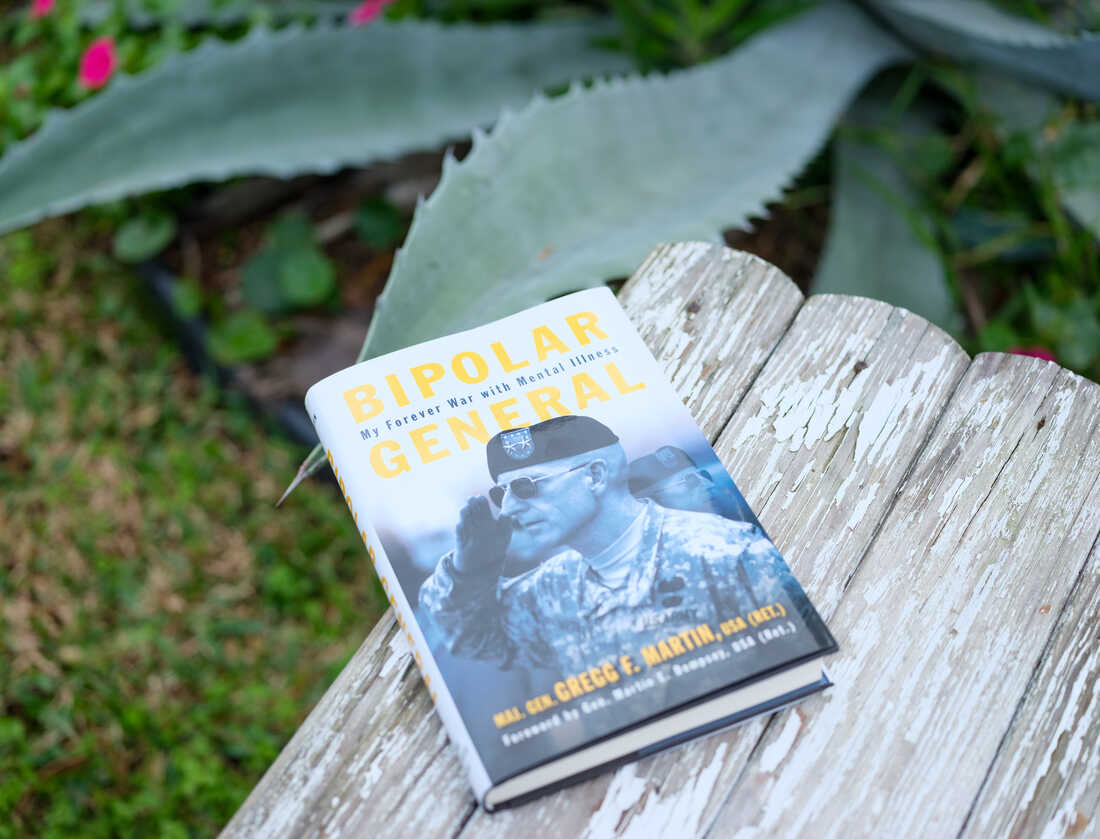

Bipolar disorder has shed some of its stigma in recent years, with celebrities and politicians going public about their struggles with mental illness. And the military has changed its approach to mental health in the 20 years since Martin’s tour in Iraq. But many in the military still fear a mental health diagnosis could derail their careers. That’s one reason Martin has written a memoir called Bipolar General: My Forever War with Mental Illness. Experts in the field credit Martin with helping to break down the military taboo on getting help.

“If you’re in the military, you are supposed to project this tough image,” says Dr. Alex Leow, a psychiatrist and biomedical engineer at the University of Illinois Chicago who treats and studies bipolar. Martin gave the keynote speech at the International Bipolar Foundation’s annual conference in 2023, where Leow met him.

Leow says people on the bipolar spectrum are often attracted by the way a military career rewards aggressive, daring behavior. Unfortunately, the intensity of that work can ignite severe symptoms, she says.

“There is almost a double whammy effect. You are attracting more people on the [bipolar] spectrum into the military, but also because of the stress, because of the combat experiences … the likelihood that you actually develop symptoms is also higher,” she says.

Which is what Martin says happened to him. Iraq triggered severe symptoms – intense cycles from mania to depression. All the while, his manic side just looked like high performance to his military superiors, who kept promoting him. By the time he took command of the U.S. Army War College in 2010, delusions had taken hold.

“My bipolar disorder had increased significantly since Iraq, and now it was pouring gasoline on the flames of a very sick brain. I believed I was the smartest person in the world. I believed that I was an apostle sent by God to transform … the entire Department of Defense,” he said.

In 2012 Martin became president of the National Defense University (NDU). By this time his behavior was finally raising flags. He’d stride into a random classroom and just start lecturing.

“One of the NDU colleges actually took to posting a guard outside the door. And if I came into the building, he was to notify the commandant immediately so he could divert me from going into a lecture hall. That’s how bad it was,” said Martin.

Gregg Martin says writing Bipolar General and working to normalize mental health in the military is the most important work of his life.

Michelle Bruzzese for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Michelle Bruzzese for NPR

Gregg Martin says writing Bipolar General and working to normalize mental health in the military is the most important work of his life.

Michelle Bruzzese for NPR

In 2014 he was summoned, along with his wife, by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Martin Dempsey. Dempsey was a friend, and they’d worked together in Iraq and Germany; in fact Dempsey was the one who picked Gregg Martin to lead NDU.

“Gen. Dempsey walked across the office, gave me a big hug, said, ‘Gregg, I love you like a brother. You’ve done an unbelievable job. You have until 1700 hours today to resign, or I will fire you and I’m ordering you to get a mental health evaluation this week at Walter Reed,’ ” Martin recalled.

An end and a beginning

Martin’s 36-year-long Army career was ending, but it still took two years of what Martin calls untreated bipolar hell to get care.

His Army doctors did him what he and they believed was a favor by not putting the diagnosis in his records right away, allowing Martin to retire instead of being medically discharged. Looking back Martin doubts the wisdom of that decision.

Then he fell into the sometimes-lengthy gap between military health care and getting enrolled with the Veterans Health Administration. At the VA in New Hampshire he finally got prescribed medications to treat his mania and depression.

And that’s the good news: Bipolar is treatable, says Dr. Tamara Campbell, who directs the VA’s office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention.

“People go on to live very productive, high-quality lives being treated for bipolar. There is no reason for anyone in the country to suffer alone. We want to treat you. We’re here for you,” she says.

The VA now treats over 130,000 vets per year for bipolar disorder. Since January of 2023, a vet in crisis can now go to any VA or non-VA facility and get emergency care free of charge. VA has increased its mental health staff by 54% in the past five years.

But demand for mental healthcare is surging nationwide, and VA estimates it takes 22 days to get a new VA mental health appointment. Academic studies estimate the wait can be as longs as 45 days, and it’s even longer for a private medical appointment.

Still, Dr. Campbell says the sooner vets get treated for bipolar, the better. And she thinks Gen. Martin’s willingness to speak publicly will help bring more people in.

“God put me here to do big things,” says Martin. That was not a delusion, he says.

“That’s actually true because what I’m doing in terms of mental health advocacy and telling my bipolar story is the most important thing I’ve ever done in my life,” he says.

When he’s done, Martin says, more civilians and veterans will see bipolar disorder like they see diabetes — a disease with a treatment and no shame.