Wealth & Personal Finance decided to try an experiment. With the help of investment platform AJ Bell, we pitted six portfolios against each other, each with a different popular strategy. For each, we asked this question: if an investor had put £10,000 into this portfolio ten years ago, how much money would they have made by now?

The answer shocked Laith Khalaf head of investment analysis at AJ Bell, who ran the figures, and surprised us at Wealth & Personal Finance, too.

Investors are endlessly searching for the winning strategy that will give them the edge. Everyone from ordinary investors to expert fund managers seek out that holy grail – the formula that will grow their wealth by a bit more than everyone else each year.

Many believe they have found it. Some buy a portfolio and hold it for years, come what may. Others opt for so-called contrarian investing – buying whatever is unloved at the time. Another bunch hoover up whatever’s looking cheap.

We wanted to find out who is right. Our portfolios are not comprised of individual stocks or funds. Instead, to be more representative, they are made up of investment sectors, such as UK all-company funds, North American funds, global funds and technology funds. These are all sectors defined by the Investment Association – an industry body. The six portfolios were:

Stand out from the crowd: Herd investors who blindly followed their peers performed worse over ten years than performance chasers

1) Performance chasers

In this portfolio, we imagined that, at the start of the ten-year period in 2014, the investor put their £10,000 into healthcare, the sector that enjoyed the best performance the previous year. Then, on January 1 of every subsequent year, the investor moved their full portfolio into the best-performing sector of the year just gone. In other words, they were always investing in last year’s winners.

2) Buy and hold global

This investor put their £10,000 into a global fund, which moves up and down with the global stock market. They left it untouched for a decade.

3) Egg spreaders

Here, we imagined that at the beginning of the ten-year period, the investor split their £10,000 equally between UK funds, US funds, European funds, Japanese funds and global emerging market funds. In other words, rather than putting their eggs into one basket, they bought a bit of everything, and rebalanced them each year.

4) Herd Investors

This investor started with their £10,000 in the investment sector that was most popular in 2013. Then every year, they shifted their money into the sectors that most people bought in the previous year, regardless of performance.

5) Contrarians

For this portfolio, the investor did the exact opposite of herd investors. They put their £10,000 into the least popular sector from the previous year, and did the same on January 1 for the full ten-year period.

6) Bargain hunters

Here the investor put their £10,000 into the worst performing sector from the year before in each year.

And the winner is…

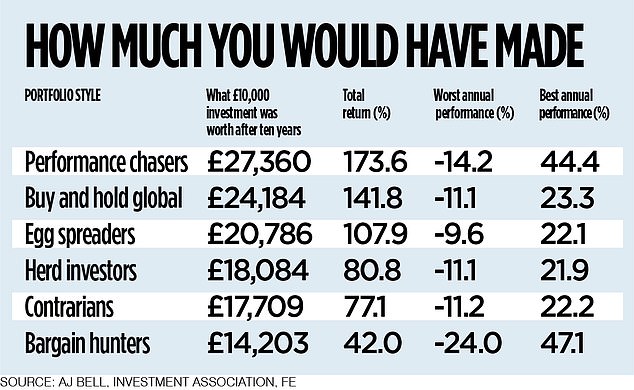

Performance chasers – and by a long way. After ten years, their £10,000 investment would be worth an impressive £27,360. The next best was the buy and hold global investor, with £24,184.

The biggest loser was the bargain hunter, turning the investment into £14,203. But even this portfolio managed to beat inflation – £10,000 in 2014 is worth £13,150 today.

Laith Khalaf says: ‘Everyone knows that chasing fund performance is a fool’s errand. Except for the fact that in the last ten years, it’s yielded terrific results. Investors who each January had put their money into the best performing fund sector of the previous year would be rolling in it, registering a 173.6 per cent return over the decade.’

But was it a fluke?

You could argue that the last decade has not been typical for investors. It was a period in which US technology companies – the likes of Facebook’s owner, Meta, and Google’s owner, Alphabet – drove a good chunk of the growth in global stock markets. Their star kept rising. As these were driving growth year after year, it is perhaps no surprise that the performance chaser portfolio did well over that period.

So, we asked AJ Bell to try the same experiment, using the same portfolio styles, over other ten-year periods. And it couldn’t find a single ten-year period in the past 30 years when the performance chaser did not beat a buy and hold strategy – which is what is usually recommended to ordinary investors by the investment industry. Moreover, look further and you see that the technology sector was the top performer in only two of the ten years – and India, healthcare and commodities were all also two-time top performers.

So, should you become a performance chaser?

Not necessarily – and for several reasons. First, past performance is no guarantee of future returns – even if a strategy has performed well for a number of years.

Jason Hollands, at investment platform Bestinvest by Evelyn Partners, says: ‘Chasing returns can work for a while, then suddenly the best performers change. Unless you have a crystal ball, you cannot know when it will happen. It may catch you out.

‘If you chase performance, you are also far more likely to be exposed when bubbles emerge. In the 1990s, when the dotcom bubble burst, investors who had been piling into these most-popular stocks would have suffered badly.’

Second, performance chasers have endured a stomach-lurching ride. In the past ten years, the biggest annual drop for performance chasers was 14.2 per cent. But if you go back to 2000, performance chasers would have suffered an 31 per cent fall – compared with a 5 per cent fall experienced by buy and hold global investors.

Khalaf adds: ‘In 2008, a performance chaser portfolio would have dropped by 45 per cent, against a 24 per cent fall for a buy and hold global portfolio. In 2009, it would have dropped again – this time by 11 per cent – while the buy and hold global portfolio would have rebounded by 23 per cent.’ Ouch.

Third, it is all well and good comparing the performance of hypothetical portfolios. But it is a bit more complicated if you’re managing one of them. In the case of a buy and hold portfolio, you literally have to do just that. Simply buy a well-diversified portfolio of sectors, and geographies and then sit tight – tweaking occasionally to rebalance or if your investment goals or time horizon changes.

But were you to manage a performance chaser portfolio – or one of the others, such as contrarian, herd or bargain hunter – you would have to work out which funds to buy and sell each year to stick to your chosen strategy, overhaul your portfolio every year, and probably incur fees every time you bought and sold.

A compromise?

A buy and hold global portfolio works on the premise that global stock markets tend to rise over the long term, but that few of us effectively predict which sectors will perform best so may as well hold a bit of each and hope for the best.

For many investors – especially those who want less drama – this is probably a good starting point.

However, if you have certain convictions – about a particular investing style or trend, or a sector, geography or company you think will do better than the average – you could always tweak a balanced portfolio to express it. Buy a bit more of these investments – but don’t plough all your cash into them in case you’re wrong.

- What’s your investing style? Email rachel.rickard@mailonsunday.co.uk

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money, and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.