“I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration. I will face my fear. I will permit it to pass over me and through me. And when it has gone past I will turn the inner eye to see its path. Where the fear has gone there will be nothing. Only I will remain.”

— Bene Gesserit “Litany Against Fear” from Frank Herbert’s Dune

For most of us, the how-to books on our shelves represent a growing to-do list, not advice we’ve followed.

Several of the better-known tech CEOs in San Francisco have asked me at different times for an identical favor: an index card with bullet-point instructions for losing abdominal fat. Each of them made it clear: “Just tell me exactly what to do and I’ll do it.”

I gave them all of the necessary tactical advice on one 3×5 card, knowing in advance what the outcome would be. The success rate was impressive… 0%.

People suck at following advice. Even the most effective people in the world are often terrible. There are at least two reasons:

1. Most people have an insufficient reason for action. The pain isn’t painful enough. It’s a nice-to-have, not a must-have. There has been no “Harajuku Moment.”

2. There are no reminders. No consistent tracking = no awareness = no behavioral change. Consistent tracking, even if you have no knowledge of fat-loss or exercise, will often beat advice from world-class trainers.

But what is this all-important “Harajuku Moment”?

It’s an epiphany that turns a nice-to-have into a must-have. It applies to fat loss, to getting your finances in order, to getting your relationships in order, and to getting your life in order. No matter how many bullet points and recipes experts provide, most folks will need a Harajuku Moment to fuel the change itself.

Chad Fowler knows this.

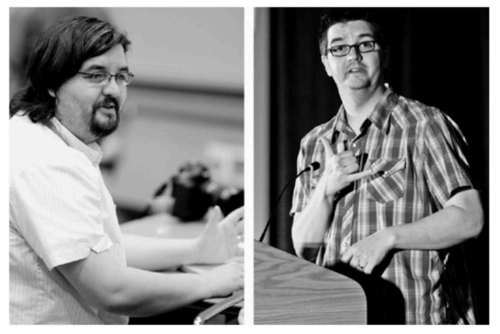

Chad is a General Partner and CTO at BlueYard Capital. He was also co-organizer of the annual RubyConf and RailsConf conferences, where I first met him. Our second meeting was in Boulder, Colorado, where he used his natural language experience with Hindi to teach a knuckle-dragger (me) the primitive basics of Ruby.

Chad is an incredible teacher, gifted with analogies, but I was distracted in our session by something he mentioned in passing. He’d recently lost 70+ pounds in less than 12 months.

It wasn’t the amount of weight that I found fascinating. It was the timing. He’d been obese for more than a decade, and the change seemed to come out of nowhere. Upon landing back in San Francisco, I sent him one question via email:

What were the tipping points, the moments and insights that led you to lose the 70 lbs.?

I wanted to know what the defining moment was, the conversation or realization that made him pull the trigger after 10 years of business as usual.

His answer is contained in this post.

Even if you have no interest in fat-loss, the key insights (partial completeness, data, and oversimplification among them) will help you get closer to nearly any physical goal—lift 500 pounds, run 50 kilometers, gain 50 pounds, etc. —and it applies to much more in life.

But let’s talk about one apparent contradiction upfront: calorie counting. I regularly thrash calorie counting, and I’m including Chad’s calorie-based approach to prove a point. The 4-Hour Body didn’t exist when Chad lost his weight, and there are far better things to track than calories. But would I recommend tracking calories as an alternative to tracking nothing? You bet. Tracking anything is better than tracking nothing. The Hawthorne effect can be applied to yourself.

If you are very overweight, very weak, very inflexible, or very anything negative, tracking even a mediocre variable will help you develop awareness that leads to better behavioral changes.

This underscores an encouraging lesson: you don’t have to get it all right. You just have to be crystal clear on a few concepts. Results follow.

Much of the bolding in Chad’s story is mine.

Enter Chad Fowler . . .

The Harajuku Moment

Why had I gone 10 years getting more and more out of shape (starting off pretty unhealthy in the first place) only to finally fix it now?

I actually remember the exact moment I decided to do something.

I was in Tokyo with a group of friends. We all went down to Harajuku to see if we could see some artistically dressed youngsters and also to shop for fabulous clothing, which the area is famous for. A couple of the people with us were pretty fashionable dressers and had some specific things in mind they wanted to buy. After walking into shops several times and leaving without seriously considering buying anything, one of my friends and I gave up and just waited outside while the others continued shopping.

We both lamented how unfashionable we were.

I then found myself saying the following to him: “For me, it doesn’t even matter what I wear; I’m not going to look good anyway.”

I think he agreed with me. I can’t remember, but that’s not the point. The point was that, as I said those words, they hung in the air like when you say something super-embarrassing in a loud room but happen to catch the one randomly occurring slice of silence that happens all night long. Everyone looks at you like you’re an idiot. But this time, it was me looking at myself critically. I heard myself say those words and I recognized them not for their content, but for their tone of helplessness. I am, in most of my endeavors, a solidly successful person. I decide I want things to be a certain way, and I make it happen. I’ve done it with my career, my learning of music, understanding of foreign languages, and basically everything I’ve tried to do.

For a long time, I’ve known that the key to getting started down the path of being remarkable in anything is to simply act with the intention of being remarkable.

If I want a better-than-average career, I can’t simply “go with the flow” and get it. Most people do just that: they wish for an outcome but make no intention-driven actions toward that outcome. If they would just do something, most people would find that they get some version of the outcome they’re looking for. That’s been my secret. Stop wishing and start doing.

Yet here I was, talking about arguably the most important part of my life—my health—as if it was something I had no control over. I had been going with the flow for years. Wishing for an outcome and waiting to see if it would come. I was the limp, powerless ego I detest in other people.

But somehow, as the school nerd who always got picked last for everything, I had allowed “not being good at sports” or “not being fit” to enter what I considered to be inherent attributes of myself. The net result is that I was left with an understanding of myself as an incomplete person. And though I had (perhaps) overcompensated for that incompleteness by kicking ass in every other way I could, I was still carrying this powerlessness around with me and it was very slowly and subtly gnawing away at me from the inside.

So, while it’s true that I wouldn’t have looked great in the fancy clothes, the seemingly superficial catalyst that drove me to finally do something wasn’t at all superficial. It actually pulled out a deep root that had been, I think, driving an important part of me for basically my entire life.

And now I recognize that this is a pattern. In the culture I run in (computer programmers and tech people), this partial-completeness is not just common but maybe even the norm. My life lately has taken on a new focus: digging up those bad roots; the holes I don’t notice in myself. And now I’m filling them one at a time.

Once I started the weight loss, the entire process was not only easy but enjoyable.

I started out easy. Just paying attention to food and doing relaxed cardio three to four times a week. This is when I started thinking in terms of making every day just slightly better than the day before. On day 1 it was easy. Any exercise was better than what I’d been doing.

If you ask the average obese person: “If you could work out for ONE year and be considered ‘in shape,’ would you do it?” I’d guess that just about every single one would emphatically say, “Hell, yes!” The problem is that for most normal people, there is no clear path from fat to okay in a year. For almost everyone, the path is there and obvious if you know what you’re doing, but it’s almost impossible to imagine an outcome like that so far in the distance.

The number-one realization that led me to be able to keep doing it and make the right decisions was to use data.

I learned about the basal metabolic rate (BMR), also called resting metabolic rate, and was amazed at how many calories I would have to eat in order to stay the same weight. It was huge. As I started looking at calorie content for food that wasn’t obviously bad, I felt like I’d have to just gluttonously eat all day long if I wanted to stay fat. The BMR showed me that (1) it wasn’t going to be hard to cut calories, and (2) I must have been making BIG mistakes before in order to consume those calories—not small ones. That’s good news. Big mistakes mean lots of low-hanging fruit.1

Next was learning that 4,000 calories equals about a pound of fat. I know that’s an oversimplification, but that’s okay. Oversimplifying is one of the next things I’ll mention as a tool. But if 4,000 is roughly a pound of fat, and my BMR makes it pretty easy to shave off some huge number of calories per day, it suddenly becomes very clear how to lose lots of weight without even doing any exercise. Add in some calculations on how many calories you burn doing, say, 30 minutes of exercise and you can pretty quickly come up with a formula that looks something like:

BMR = 2,900

Actual intake = 1,800

Deficit from diet = BMR– actual intake = 1,100

Burned from 30 minutes cardio = 500

Total deficit = deficit from diet – burned from 30 minutes cardio = 1,600

So that’s 1,600 calories saved in a day, or almost half a pound of bad weight I could lose in a single day. So for a big round number, I can lose 5 pounds in a week and a half without even working too hard. When you’re 50 pounds overweight, getting to 10% of your goal that fast is real.

An important thing I alluded to earlier is that all of these numbers are in some ways bullshit. That’s okay, and realizing that it was okay was one of the biggest shifts I had to make. When you’re 50–70 pounds overweight (or I’d say whenever you have a BIG change to make), worrying about counting calories consumed or burned slightly inaccurately is going to kill you. The fact of the matter is, there are no tools available to normal people that will tell us exactly how much energy we’re burning or consuming. But if you’re just kinda right and, more important, the numbers are directionally right, you can make a big difference with them.

Here’s another helpful pseudo-science number: apparently, 10 pounds of weight loss is roughly a clothing size [XL → L → M]. That was a HUGE motivator. I loved donating clothes all year and doing guilt-free shopping.

As a nerd, I find myself too easily discouraged by data collection projects where it’s difficult or impossible to collect accurate data. Training myself to forget that made all the difference.

Added to this knowledge was a basic understanding of how metabolism works. Here are the main things I changed: breakfast within 30 minutes of waking and five to six meals a day of roughly 200 calories each. How did I measure the calories? I didn’t. I put together an exact meal plan for just ONE week, bought all the ingredients, stuck to it religiously. From that point on, I didn’t have to do the hard work anymore. I became aware after just one week of roughly how many calories were in a portion of different types of food and just guessed. Again, trying to literally count calories sucks and is demotivating. Setting up a rigid template for a week and then using it as a basic guide is sustainable and fun.

Just a few more disconnected tips:

I set up a workstation where I could pedal on a recumbent bike while working. I did real work, wrote parts of The Passionate Programmer, played video games, chatted with friends, and watched ridiculous television shows I’d normally be ashamed to be wasting my time on, all while staying in my aerobic zone. I know a lot of creative people who hate exercise because it’s boring. I was in that camp too (I’m not anymore. . . it changes once you get into it). The bike/desk was my savior. That mixed with a measurement system:

I got a heart rate monitor (HRM) and started using it for EVERYTHING. I used it while pedaling to make sure that even when I was having fun playing a game I was doing myself some good. If you know your heart rate zones (easy to find on the Internet), the ambiguity non-fitness-experts feel with respect to exercise is removed. Thirty minutes in your aerobic zone is good exercise and burns fat. Calculate how many calories you burn (a good HRM will do it for you), and the experience is fun and motivating. I started wearing my HRM when I was doing things like annoying chores around the house. You can clean house fast and burn serious fat. That’s not some Montel Williams BS. It’s real. Because of the constant use of an HRM, I was able to combine fun and exercise or annoying chores and exercise, making all of it more rewarding and way less likely I’d get lazy and decide not to do it.

Building muscle is, as you know, one of the best ways to burn fat. But geeks don’t know how to build muscle. And as I’ve mentioned, geeks don’t like to do things they don’t know are going to work. We like data. We value expertise. So I hired a trainer to teach me what to do. I think I could have let go of the trainer after a few sessions, since I had learned the ‘right’ exercises, but I’ve stayed with her for the past year.

Finally, as a friend said of my difficulty in writing about my insights for weight loss, a key insight is my lack of specific insights.

To some extent, the answer is just “diet and exercise.” There were no gimmicks. I used data we all have access to and just trusted biology to work its magic. I gave it a trial of 20 days or so and lost a significant amount of weight. Even better, I started waking up thinking about exercising because I felt good.

“It was easy.”

It was easy for Chad because of his Harajuku Moment. So let’s get to it:

What’s a small step you could take today? Right now?

You’ll almost never have complete information, and you don’t generally need it. It’s often an excuse for avoiding something uncomfortable. Who could you call or email today to get the bare minimum needed for your next step?

What is the cost of your inaction? This is important. What is your status quo costing you, and how can you make the pain painful enough to drive you forward? Do this exercise.

What’s a single decision you could make that, like Chad’s one-week meal plan, removes a thousand decisions?

You don’t need more how-to information.

You need 1) a painful and beautiful reckoning (e.g., what does life look like if you leave this as-is for 3-5 years?), and 2) simple actions that compound over time.

So what’s next?

This post was adapted and updated from The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-Loss, Incredible Sex, and Becoming Superhuman by Timothy Ferriss.

TOOLS AND TRICKS

“Elusive Bodyfat: Where Are You Really?“ in The 4-Hour Body. To find your own numbers and create a simple system that works, this chapter will help.

Clive Thompson, “Are Your Friends Making You Fat?” New York Times, September 10, 2009. Reaching your physical goals is a product, in part, of sheer proximity to people who exhibit what you’re targeting. This article explains the importance, and implications, of choosing your peer group.

End of Chapter Notes

1 Tim: This type of low-hanging fruit is also commonly found by would-be weight gainers when they record protein intake for the first time. Many are only consuming 40–50 grams of protein per day.

Related and Recommended

The Tim Ferriss Show is one of the most popular podcasts in the world with more than 900 million downloads. It has been selected for “Best of Apple Podcasts” three times, it is often the #1 interview podcast across all of Apple Podcasts, and it’s been ranked #1 out of 400,000+ podcasts on many occasions. To listen to any of the past episodes for free, check out this page.