The redundancy avalanche rocking the worldwide technology sector over the past couple of years shows few signs of slowing down.

Many of the industry’s giants have seen their share prices test record highs on the back of market exuberance over artificial intelligence developments, helping to mask the pressures of a higher interest rate environment.

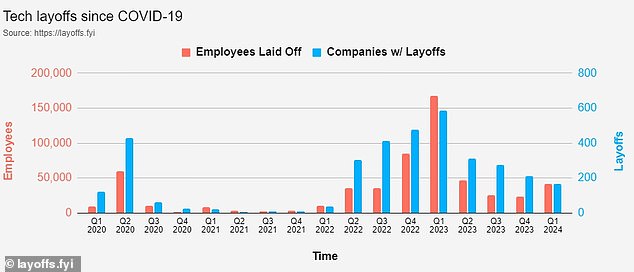

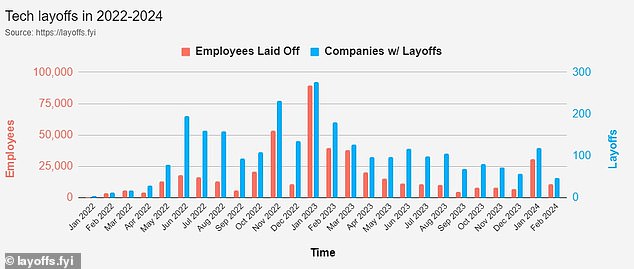

But tech businesses have announced over 41,000 job cuts since the beginning of 2024, according to industry tracker Layoffs.fyi, with January marking the worst period for the workforce in 10 months.

Redundancies: Tech businesses have announced over 41,000 job cuts since the beginning of 2024, according to industry tracker Layoffs.fyi

Microsoft revealed last month that approximately 1,900 posts at Xbox and Activision Blizzard, the video game publisher behind Call of Duty, would be axed to provide a more ‘sustainable cost structure’.

Five days later, Paypal and Jack Dorsey’s payments platform Block each confirmed they would slash their workforce by about 10 per cent.

Others to make cutbacks this year include eBay, Snap, furniture retailer Wayfair, Google owner Alphabet and Amazon, which is shrinking its Twitch, Prime Video, and MGM Studios divisions.

These companies also implemented redundancies in 2023, when the global tech industry let go 262,735 employees in total, compared to 165,269 the previous year.

Tech-focused recruiters have borne a knock-on effect, such as white-collar specialist Robert Walters and Partway Group, formerly Parity Group, which both shrank their headcount last year.

Interest rate hikes and over-hiring hangover

During the first half of the pandemic, tech businesses embarked on a hiring binge as millions of extra people worked and socialised from home.

However, since Covid-related restrictions ended, the shift back to more analogue lifestyles has depressed growth rates and left tech firms with bloated payrolls.

‘We cannot underestimate the effect pandemic over-hiring had on the tech sector,’ says Chris Eldridge, chief executive of Robert Walters’ UK and Ireland division.

‘As demand has continued to wane on those specialisms that experienced a huge spike during Covid, the cuts have continued.’

Digital slide: The redundancy avalanche rocking the worldwide technology sector over the past couple of years shows few signs of slowing down

Redundancies: The global technology industry let go 165,269 employees in 2022 and 262,735 last year amid rising interest rates and the loosening of Covid-related restrictions

Between 2019 and 2022, Facebook owner Meta almost doubled employee numbers to 87,000. Its headcount has subsequently fallen by around 20,000.

When announcing layoffs in November 2022, founder Mark Zuckerberg blamed his incorrect prediction that the pandemic-induced jump in online activity ‘would be a permanent acceleration’ for some of Meta’s investments turning sour.

The tech industry’s problems have also been compounded by weak economic growth and rising interest rates.

Higher interest rates are generally considered bad news for high-valued tech stocks, which are mostly valued on their future profit potential. Future cash flows are typically seen as less valuable in a high rate environment.

Some of the largest tech firms have been cushioned from this effect by interest earned on their cash balances, but they still face pressure to cut costs and bolster present profitability.

Reversal: Between 2019 and 2022, Facebook owner Meta almost doubled employee numbers to 87,000, yet that number has subsequently fallen by around 20,000

And higher rates have elevated borrowing costs and depressed stock prices among many small and mid-cap companies, whose debt payments tend to constitute a greater share of earnings.

Chris Beauchamp, an analyst at IG Group, told This is Money ‘we are unlikely to see a complete stop to the layoffs’ until interest rates come down.

Inflation has fallen considerably across the UK, US and Europe over the past year, lifting hopes that central banks will soon cut rates.

In the meantime, investors are still urging tech businesses to implement bold cost-cutting measures to improve profitability and share prices.

Bloomberg analysis found American tech giants saw their stocks increase by an average of 5.6 per cent in the month after they unveiled redundancies.

‘The pressure on tech firms to outperform is now all the greater following the big share price gains, and job cuts remain an area where costs can be cut,’ Beauchamp says.

Chasing the AI boom

But while the tech sector is moderating hiring and investment, it is simultaneously redirecting a lot of spending towards developing artificial intelligence.

Enterprise software giant SAP announced last month that it was restructuring 8,000 posts in order to concentrate on areas like business AI, while Google’s latest cuts came amid the launch of Gemini, a potential rival to Microsoft’s ChatGPT.

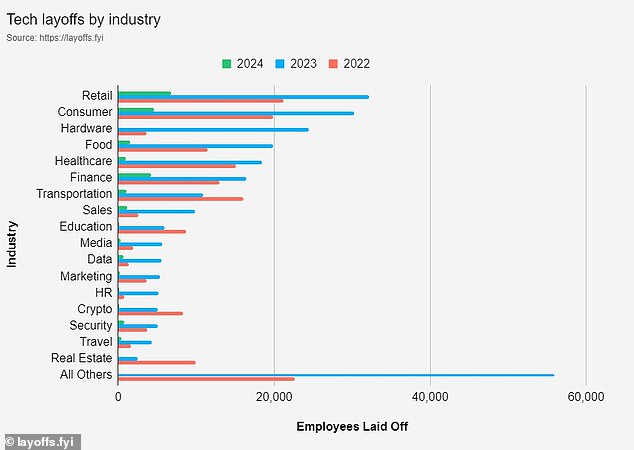

Sector breakdown: Since the beginning of 2022, industries like retail, consumer and hardware have laid off huge numbers of technology workers

The possible gains from AI are enormous; consultancy PwC estimates it could add $15.7trillion to world GDP by 2030, equivalent to 45 per cent of all economic gains.

Robert Waters’ Eldridge notes that demand for machine learning specialists among professional services firms across the British Isles has jumped by 29 per cent over the past year.

The future of tech jobs

There have been similar spikes in cyber-security roles, something Eldridge describes as ‘virtually recession-proof’ given the threat cyberattacks pose in all market environments.

Data breaches cost companies an average of $4.45million in 2023, a 15 per cent leap in three years, according to IBM, a figure sure to highlight the need to invest in robust online security measures.

Another major threat, climate change, is driving demand among renewable energy firms for software developers and data analytics specialists, points out an SThree spokesperson.

They further observe a greater need among the financial services sector for data scientists and manufacturers for automation and robotics experts.

However, AI’s advances inevitably mean some tech occupations will be replaced by machines, causing dramatic disruption to the global employment market.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Christopher Pissarides recently warned that students studying science, technology, engineering, and mathematics courses might not find enough vacancies catering to their respective skills.

In an interview with Bloomberg, the London School of Economics professor said staff in particular IT careers might be sowing their ‘own seeds of self-destruction’ by working on AI projects that will wipe out their jobs.

‘The skills that are needed now — to collect the data, collate it, develop it, and use it to develop the next phase of AI or, more to the point, make AI more applicable for jobs — will make the skills that are needed now obsolete because it will be doing the job,’ he said.

Prioritising: While the tech sector is moderating hiring and investment, it is simultaneously redirecting a lot of spending towards developing artificial intelligence

Pissarides predicts that traditional professions involving face-to-face interaction, creativity, and empathy, such as healthcare and hospitality, will prosper in the future because they are less likely to be replaced by AI.

His comments are unlikely to dissuade many teenagers and 20-somethings captivated by the generous salaries and perks offered by tech firms for work on demanding but highly rewarding projects.

Historically, concerns about technological advancement leading to a future of mass unemployment have often turned out to be dramatically inaccurate and alarmist.

and studies published by Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank, and the International Labour Organisation last year concluded that AI is more likely to create and augment jobs than replace them.

Many roles that were nonexistent just a few decades ago are now commonplace: podcast producer, driverless car engineer, mobile app developer, and SEO analyst.

So are whole new industries with the suffix -tech in their name: fintech, nanotech, proptech, insurtech, agritech, and MADtech (marketing and advertising).

As the ILO points out: ‘Twenty years ago, there were no social media managers; thirty years ago, there were few web designers, and no amount of data modelling would have rendered a priori predictions concerning a vast array of other occupations that have emerged in the past decades.’

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money, and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.