Dudits/iStock via Getty Images

Mowi ASA (OTCPK:MHGVY) is the world’s largest salmon farmer, producing close to 20% of the world’s farmed salmon.

The company is a good operator in a cyclical market, with low leverage and high cycle-average margins and returns on capital. I believe the company is well-positioned to savor extra rents from its scarce salmon farming licenses.

However, I believe the company’s market will be disrupted in the next decade, and its margins will eventually fall. For that reason, I don’t think that the current multiples on cycle-average earnings (EV/NOPAT is my preferred measure) are justified.

The salmon market

I recently wrote an article on the salmon market and the trends I expect to see playing out in the future. I propose readers to visit the article, only summarized here.

Most of the salmon in the world is farmed, not fished. The salmon market suffers from supply-driven cycles because salmon takes three years from hatch to harvest, and it can only be sold for a short period of time while fresh.

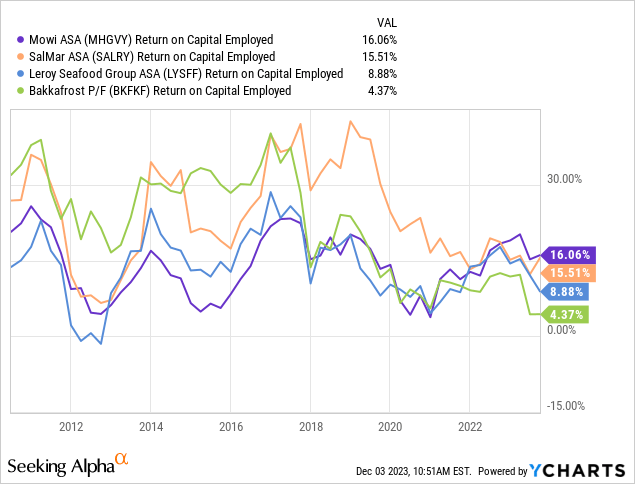

However, in the past few years, the cycles have been less severe for companies, and most large salmon farmers from Norway have enjoyed average returns on capital above 12%. The reason is that a lack of farming licenses limits supply, given that salmon can only be cultivated in cold-water fjords. The largest producers are Norway (50%+), Chile (25%), Scotland, the Faroe Islands, Canada, and Iceland. All of them are close to the biological limit of production. Increasing the amount of salmon in these waters could guide to environmental damage and higher mortalities.

Because of the supply limit, salmon is increasingly profitable, and the companies that own licenses to produce it are benefited.

Unfortunately for salmon farmers, rents attract capital trying to capture that extra return. For example, the Norwegian government recently created a 25% tax on sea-farmed salmon, arguing that the extra profits were generated not by business but by owning a limited natural resource.

Capitalists are also after the farmers’ profits. Many public and private companies are developing alternative systems to farm salmon, the most advanced of which is land-based farming. These systems are currently unprofitable and demand a lot of capital. Still, I believe that during the next decade, so much capital will be attracted to the sector that costs will become competitive with fjord-based salmon.

Once land-based salmon is competitive enough, the rents generated by the fjord licenses will be destroyed for all players. I expect that after land-based substitutes are extended, all players will be cyclically unprofitable because of the characteristics of the new market (high CAPEX, long production cycle, commodity, short shelf life, technically unlimited production capacity, etc.)

Mowi, the largest player in the market

Mowi is the largest salmon producer, accounting for nearly 500 thousand tons of the 2.5 million tons produced annually, or close to 20% of the market.

The company is geographically diversified into all large producing countries, although most of its revenues and profits (more than 70% in FY22) come from Norway. The reason is that Norway and the Faroe Islands are the most competitive geographies by a large stretch. This is caused by several reasons, including closeness to consumer markets (Europe and the US), high productivity, and low biological and environmental risk (a problem that affects Chile and Canada a lot more).

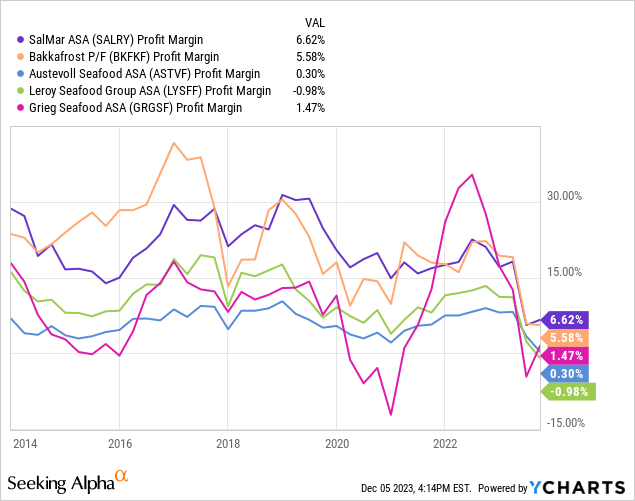

Regarding capital allocation, as seen in the ROCE charts above, Mowi’s margins are less volatile than its peers across the cycle, and the company has not run into operating losses in more than a decade.

Mowi is not heavily leveraged, with about $2 billion in net debt (or about 4x cycle-average EBIT) and most maturities after 2027. It has consistently returned capital to shareholders through dividends at a policy payout ratio of 50%.

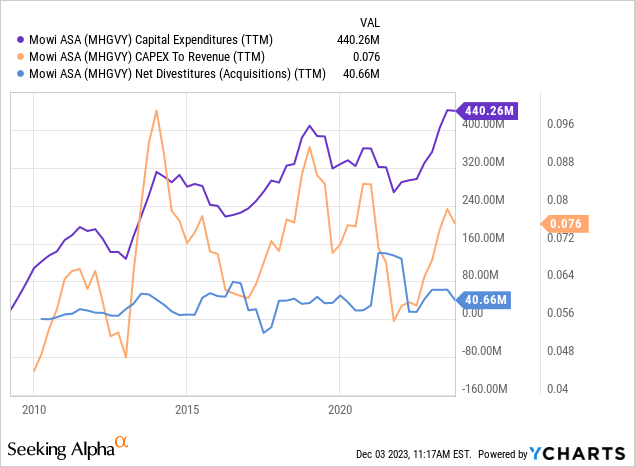

Mowi keeps investing in the salmon market, predominantly organically. The company integrates from breeding to harvest, including genetics and feed production.

Strategy

All players in the salmon market grasp the existing supply limitations, but their strategies toward them are different.

Mowi has decided not to invest in alternatives (land and offshore cultivation) but rather focus on post-smolt production, the step on the chain where salmon are still grown in land-based facilities before they are moved to the sea.

By focusing on post-smolt production, the company enjoys two benefits: it can boost the efficiency of its fjord licenses, grow more salmon traditionally and marginally boost supply; and it also gains valuable go through in land-based farming. Mowi either believes that land-based farming will not be a competitive technology or (more strategically) that it does not benefit from investing in the technology because it will destroy its rents in the future.

Prospects

Mowi is constrained in terms of supply. The company operates at close to full capacity in Norway, where allowed biomass has not grown for the past three years. Chile is not issuing new licenses, and although Mowi has close to 70% theoretical spare capacity in Chile (only using one-third of its licenses), the country’s costs are not very competitive in the worldwide market because of heightened biological risks (Chile has suffered from large mortalities in 2010, 2015/6 and 2021). Something similar happens in Canada. The remaining producing countries are small geographically, and their markets could not represent much of Mowi’s production.

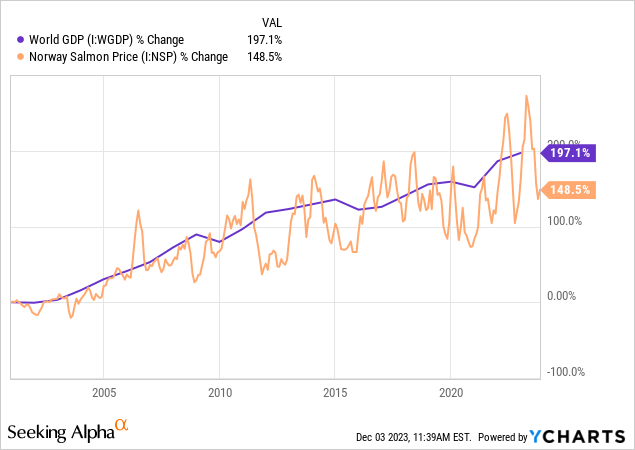

Given the supply constraints, most of Mowi’s future growth has to come from higher salmon prices and better profitability. As the chart below shows, salmon prices have shown an approximately constant CAGR of 4% per year, above inflation and closer to global GDP growth.

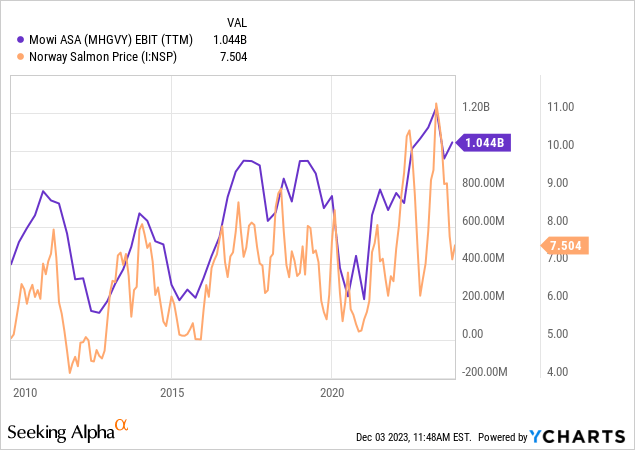

How much of that price boost is incremental profitability is difficult to know, but Mowi’s profits have moved pretty in line with salmon prices. One could expect that if the future cycles keep prices between $6 and $10 per kilogram, then Mowi could easily produce $800 million in average EBIT, compared to an average of $600 million for the past decade, with prices between $5 and $8.

Most of Mowi’s profits are generated in Norway, which has recently imposed an extra 25% tax on the profit generated from growing fish in the sea. The company expects the tax to boost its effective tax rate by 10 percentage points only. I would expect 15% to be more conservative. Given Norway’s 22% corporate income tax, Mowi’s effective rate should be closer to 37%. This gives us a NOPAT of $500 million, growing at an average of 4% yearly.

encourage, as explained in the salmon market section, I expect the salmon market to become drastically less profitable and more cyclical in about a decade once land-based or offshore cultivated salmon enters the market competitively. This would drastically reduce Mowi’s terminal value.

Can Mowi acquire some of its smaller competitors? Potentially, these players trade at relatively reasonable multiples and could represent a significant boost in cycle-average EBIT. However, the company has not stated that interest and should probably leverage to acquire these competitors.

Current valuation and conclusions

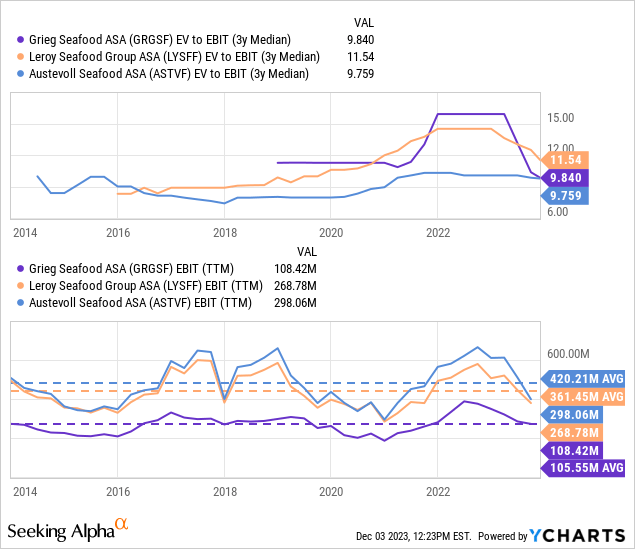

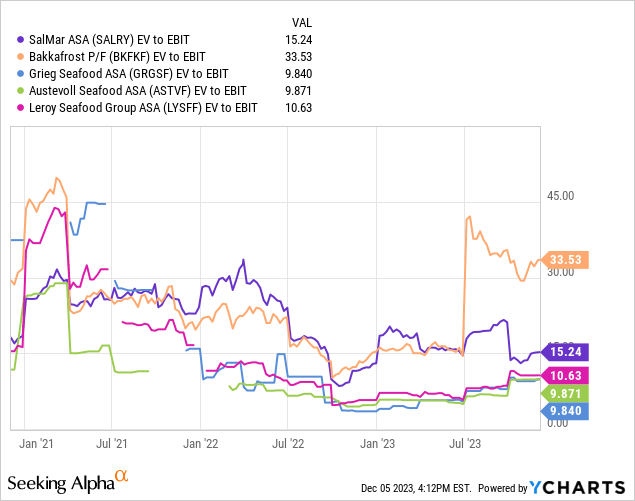

Mowi’s peers are valued in two groups. Salmar and Bakkafrost trade at upper twenties EV to average NOPAT multiples, while smaller players trade at lower multiples. Here, for comparison, we use EV/EBIT, which can be converted to EV/NOPAT by dividing the multiple by 0.63, corresponding to a 37% tax rate.

In my opinion, the main reason for the difference is the relation of EBIT to debt service costs. The smaller players admire Grieg, Leroy, and Austevoll may not create sufficient profits across the cycle to be profitable consistently, which increases liquidity risks.

Mowi currently trades at an EV of close to $11.5 billion. That represents an EV/NOPAT multiple of 23x for the cycle-average NOPAT expected. This means it belongs to the higher-quality group.

Independently of the peer comparison, I don’t find the multiple attractive. Mowi is a company that will probably not be able to grow supply, and therefore profits, rapidly and that faces a challenging future once new technologies are established.

I could be wrong in several respects: salmon farming alternatives may evolve more slowly than I expect, or they may never achieve competitiveness with fjord-based farming; Chile could overcome some of its biological challenges and offer more supply; the Norwegian taxes could decrease the value of small farmers that Mowi could acquire.

However, I believe Mowi is a good company that is interesting to follow in the future, waiting for either more reasonable prices (half the EV at least) or more information on the developments in the land-based farming segment.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.