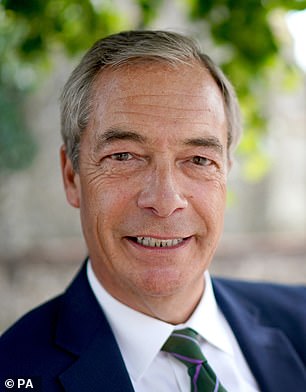

A terrier who keeps digging: Nigel Farage

NatWest is embroiled in another potentially volcanic row with Nigel Farage. The former Ukip leader is threatening to sue if it doesn’t pay him compensation and legal costs after Coutts – its private banking arm – closed his accounts.

NatWest has a couple of days in which to stump up.

And if it doesn’t, Farage is threatening court action which he hopes will scupper Treasury plans to sell the taxpayer’s stake in a ‘Tell Sid’-type campaign.

As he puts it, the bank is not fit for a public sale until its house is in order. Oh, and he wants it to promise to stop closing accounts of customers whose views it doesn’t agree with. He also asks what reforms have been put in place so that others like him – but without such a loud voice – are not treated in the same way.

Farage is right. Who on earth would want to invest in NatWest if it has a high-profile legal row with such a dogged adversary hanging over it?

Remember, its shares fell by 35 per cent immediately after Farage went public with his account closure. Frankly, the appetite for NatWest’s shares is pretty dismal anyway, as it is for all banking shares.

Having a public-wrangling match hanging over the bank will be off-putting, especially to private investors who might have fancied a dabble.

What is more incredulous about this latest spat is that NatWest’s new top team – confirmed yesterday – must have thought they could get away with their plans without settling the mess left behind by ex-boss, Dame Alison Rose, who was forced to resign over Farage’s debanking.

It was Rose who brought the affair to a climax after she admitted to a BBC journalist that it was NatWest which closed Farage’s account, breaking client confidentiality, that most basic of banking principles. They have obviously learned nothing from the scandal, which also saw the head of Coutts sacked after it became public that the private bank had compiled a whopping Stasi-style dossier on Farage and his politics.

After such a damaging affair, NatWest should know better. The new team should invite Farage in for a fireside chat, apologise for the past, and settle. They need to be seen to have cleaned up the house.

It also beggars belief that Jeremy Hunt can plan such a massive share sale with Farage roaming at large. If the Chancellor hasn’t quite understood the damage Farage has already done to NatWest’s reputation, he must by now appreciate how powerful he remains politically.

As the results of the two by-elections show, having Farage on the sidelines is dangerous. He is a terrier, one who keeps digging until he gets his bone even if it is buried on the other side of the world.

Imagine if after the Brexit vote Farage had been given a peerage and some sort of role in negotiations, how different the last few years might have been. Better to have your enemies inside the tent. NatWest should learn from that mistake.

Been and gone

Well, that was a short recession. If January’s buoyant retail sales figures are an accurate guide, the UK has been in and out of recession, and is recovering.

But it is going to be a slow haul to growth as higher interest rates are biting deep. Those with young families who are facing massive mortgage payments and other big costs are being squeezed the most.

Which is precisely what the Bank of England wanted to achieve with its rate hikes: turn off demand. Enough is enough. Now is not the time for cowardly caution – lower rates pronto.

The Chancellor needs to be equally bold. It is understood that plans for a 2p cut in income tax in next month’s Budget have been put on hold.

That is wrong. Now is precisely the time to go ahead with tax cuts and reforms to help households and small businesses. He should do the unthinkable with business rates – abolish them altogether rather than keep fiddling with opt-outs. There are alternatives. Ask James Timpson, of Timpsons, who is bursting with great ideas for rescuing the High Street.

Lights on

April may be the cruellest month but it is also getting cheaper. Ofgem is likely to confirm next week that energy bills will fall in April by nearly £300 a year for a typical household, the lowest in two years.