With interest rates at 5.25 per cent, it has become increasingly hard to press the case for investing over cash. Many people see saving as risk-free although it isn’t because of the erosive power of inflation, currently chugging along at 6.7 per cent. In contrast, they view equities as inherently risky.

It’s an understandable mindset, especially given the challenging economic backdrop and the ongoing cost-of-living crisis. Financial preservation is the order of the day.

Yet, when it comes to building long-term wealth – through a pension or an Individual Savings Account – the argument for investing (regularly) in equities remains as robust as ever.

I was reminded of this a few days ago when I spoke to James Thomson who has just completed 20 years as manager of Rathbone Global Opportunities, a £3.4 billion fund with its origins stretching back to the 1720s. Founded as a timber merchant in Liverpool by the Rathbone family, Rathbones still has a major presence in the city and an office in the iconic Port of Liverpool building, pictured.

Thomson is a rare breed among the fund management community. He has stayed loyal to this one fund and its investors through thick and thin. In return, wealth manager Rathbones, his employer, has backed him when the fund’s performance has on occasion unravelled.

Along the way, the 47-year-old admits he has made investment mistakes, but he’s learnt from them and adapted the way he runs the fund. ‘It’s my baby,’ he says. ‘I’m dedicated to it and the clients who have money invested. The fund represents my largest personal investment and my two girls, aged eight and ten, are also investors. All this sharpens my focus.’

Thomson says the case for investing remains irrefutable despite higher interest rates, talk of a global recession and heightened geopolitical risks. But it requires a long-term mindset. ‘There will always be times when investors suffer paper losses,’ he adds, ‘yet the key is to remain invested and to keep your investments locked away for when they are really needed.’

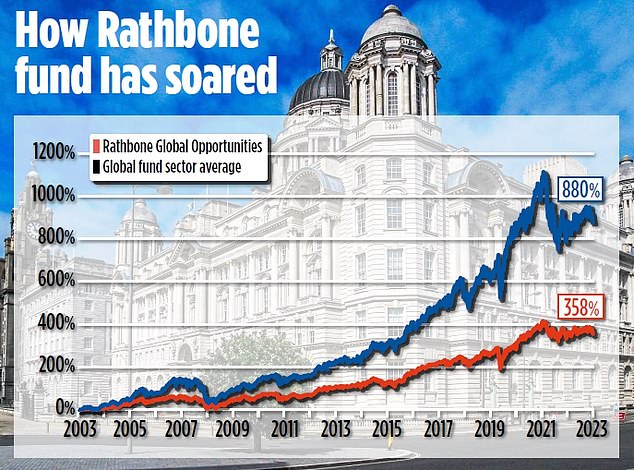

The fund’s performance numbers back his argument. Since Thomson took over its management in November 2003, it has delivered gains of 880 per cent. The fund’s ‘global’ peer group – its benchmark – has produced an average return of 358 per cent.

It hasn’t been a smooth journey, far from it. In 2008 and 2022, the fund recorded thumping losses of 39 and 20 per cent, but it has generated positive returns in 16 of the past 20 years (including the year to date) – and outperformed its peer group 17 times out of 20.Thomson has refined his investment approach over the years – and will keep tinkering with it. Yet the rules he adheres to are worth knowing about because they can be used by investors to help them run their own portfolios.

For a start, he is a big believer in diversification – one of the cornerstones of sensible long-term investing. So, no holding is allowed to account for more than four per cent of the portfolio. Once a stake approaches this limit, it is sold down.

It is what he has been doing with the fund’s position in US AI (Artificial Intelligence) specialist Nvidia, its biggest position at 3.2 per cent.

‘We’ve owned it for five years,’ he says. ‘It was our worst performing stock last year, but our best this year. So, we’ve sold a third of the position in the last few months. It doesn’t mean we are any less enthusiastic about the company’s prospects, but taking profits is no bad thing – and more importantly, I don’t want a portfolio overdependent on a stock susceptible to all the frothiness surrounding AI.’

In terms of the businesses that Thomson likes, they must be easy to understand; focused (not conglomerates); have pricing power (important when inflation is an issue); and durable.

This draws him to companies that he believes will get stronger irrespective of the prevailing economic backdrop – the likes of tech giants Amazon, Microsoft and Nvidia.

It also means stakes in ‘weather-proof’ businesses such as US retailer Costco and US garbage company Waste Connections whose products and services are always required – come rain or sunshine, recession or economic growth.

As interesting are the companies he avoids – among them unlisted concerns (too risky) and businesses whose performance is dependent on events outside of their control (such as the price of commodities).

He will also not invest in markets where he thinks specialist managers are equipped to do a better job – emerging markets, for example. So, in a nutshell, diversify, buy shares in companies that you are familiar with, don’t be scared of banking profits and use funds to get exposure to specialist investment areas such as emerging markets. And most important of all, think long-term. Don’t get shocked out of the market because of short- term turbulence.

It’s a strategy (thinking long-term) that all the best fund managers employ – for example, Terry Smith at Fundsmith Equity and Nick Train at Lindsell Train. They buy good companies and hold them. As for Thomson, he is keen to remain at the helm of Rathbone Global Opportunities for as long as his clients want him to. Another 20 years? I wouldn’t rule it out.

Shame on the banks for penny-pinching over hubs

It appears that the banks are refusing to back the introduction of banking hubs into towns where the only remaining deposit and mortgage provider is Nationwide.

This is despite the fact that such towns no longer provide small businesses and independent retailers (the lifeblood of our economy) with a bank prepared to accept their cash takings – or allow them to make cash withdrawals. This is because Nationwide does not do small business banking. Hardly a community-friendly approach from the banks, I would argue, although banks have long lost any personal connection with the customers they are in business to serve.

Hubs are shared branches that customers of all the big banks can use to do basic banking such as deposit and withdraw cash. Set up by Cash Access UK, an organisation funded by the banks, they have slowly been introduced into towns where the last bank branch (including the local Nationwide) has shut. But if a Nationwide branch remains, a hub cannot be installed.

Yet banking experts thought this impediment had been removed last month when Nationwide quietly signalled its withdrawal from Cash Access UK in order to concentrate effort on its national network of branches.

Unlike banking rivals, Nationwide sees branches as places to do business, not as financial millstones.

Quite understandably, it now sees no reason to support Cash Access UK when all the benefits of banking hubs (cost savings) go to the banks.

Rather than paying for the upkeep of its own branch, a big bank now only has to make a financial contribution towards a hub in a town where all bank outlets have gone.

Nationwide’s stepping away from Cash Access UK was seen as a way to introduce hubs into some of the towns now only served by the building society. They include communities such as Harpenden in Hertfordshire and Whitstable in Kent – two of 27 that I identified in Money Mail a month ago.

What I am hearing through the banking grapevine is that the banks are not prepared to provide Cash Access UK with the money to fund hubs in these towns, initially overlooked because of the presence of Nationwide.

If I’m right, it’s so wrong. Closing their own branches is bad enough, but penny-pinching over hubs is borderline reprehensible.

You decide on accusations of insurance profiteering

Investors in insurer Direct Line were delighted last week to see the company’s share price respond favourably to a sharp increase in premiums in the third quarter of this year. Up 68 per cent on last year’s equivalent figures.

The company, its acting chief executive said, was nicely set up for ‘improved performance going forward’. It’s just a shame that motorists have paid a heavy price – with the average insurance premium up 37 per cent year on year. In contrast, the increase in the cost of claims is in ‘high single digits’. Profiteering? I will leave you to answer that question.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money, and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.