vchal/iStock via Getty Images

Financial statements supply a snapshot of an entity’s financial health, giving insight to its operations, performance and financial strength. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) was created to progress financial accounting and reporting standards for public companies that give investors, creditors, and other capital providers information that helps them make decisions.

They are the originators of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

FASB is recognized by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission as the designated accounting standard setter for public companies. They are an independent, non-profit organization whose goal is to be transparent in providing useful information to those who use financial reports.

The Financial reporting system, however, is not perfect.

The best course I took in business school was an accounting class called “Problems in Financial Reporting” with Professor Peter Knutson. He taught that within the rules, there were occasionally different options for reporting a specific occurrence. Not surprisingly, businesses would pick the option that put them in the best light.

Many who look at financial reports quickly go to the key metric they are interested in, admire net income, and make a decision based on the bottom-line figure, without understanding the underlying steps in the calculation.

It is incumbent on the financial analyst to review the complete report to know how the figure is derived to get a true picture of the financial health of the entity.

Often the footnotes contain detailed, relevant information that many skip over. It is there that companies will bury many of the blemishes on their financial position that they chose not to highlight.

Professor Knutson emphasized that one should look for what the company is not telling you, to comprehend their true financial position.

Which brings me to the Federal Reserve Banks Combined Quarterly Financial Report as of September 30, 2023, that was quietly released during the Thanksgiving Holiday break.

Fed Operating Results

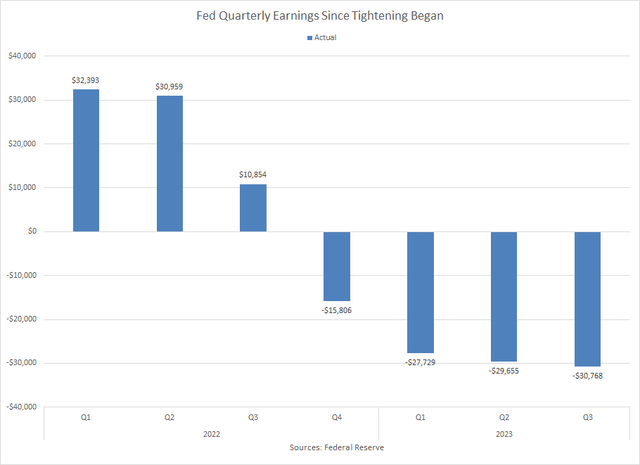

For the quarter ending September 30, 2023 the Fed lost -$30.8 billion from operations. This represents the Fed’s fourth consecutive quarterly loss and their largest quarterly loss on record.

Interest income fell by $2.9 billion to $44.3 billion, while interest expense increased by $39.2 to $72.7 billion, from the same period one year ago.

For the nine-month period ending September 30th, the Fed lost –$88.2 billion from operations, compared to a gain of $74.2 billion over the same nine-month period one year ago.

The reason for the loss is that the Fed’s assets, primarily their $5.2 trillion in US Treasury securities and $2.5 trillion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) earned a fixed rate of 2.06%, while the Fed’s $4.9 trillion of interest-bearing liabilities, comprised of bank reserves and reverse repurchase agreements, pay a current variable rate of 5.33%. As the Fed has tightened over the past year, raising the Fed Funds rate by 225 basis points, the cost of their liabilities has increased significantly, while the rate they earn on their assets has remained fixed. This negative net interest margin of paying more on their liabilities than they earn on their assets, causes the loss.

The Fed actually incurred an operating loss for the first time since 1915 during the fourth quarter of 2022 when they lost -$15.8 billion.

Cumulatively the Fed’s 12-month loss totals -$105 billion.

Yet nowhere in the Combined Quarterly Report does the Fed actually say they recorded an operating loss. The closest they come is in the last footnote on the last page when they state:

“In the fall of 2022, the Reserve Banks first suspended weekly remittances to the Treasury because earnings shifted from excess to less than the costs of operations, payment of dividends, and reservation of surplus.”

Where the Magic Happens

Normally, when an entity records a profit or a loss, it flows through to the balance sheet’s capital account. A profit increases the firm’s retained earnings or surplus, while a loss reduces the firm’s capital.

Not so at the Fed.

The Fed doesn’t use GAAP accounting rules, as defined by the independent FASB. Instead, the Fed follows the Financial Accounting Manual for Federal Reserve Banks (FAM) as approved by the Board of Governors.

Since the Fed is unique as the nation’s only central bank, it follows its own set of accounting principles. FAM procedures are not independently formulated. As such, the Fed is making up their own rules.

When the Fed records a profit, by statute, they remit their profit to the Treasury. When there is a loss, however, it is a different matter.

admire corporations that under GAAP pick the best option to present their financial position in the most favorable light, so does the Fed under FAM.

With regards to their operating loss, the Fed does not have anything to remit to the Treasury. They also don’t want to have the loss flow through to their capital account. The Fed keeps a slim capital position of $42.7 billion, and at 2.5 times their capital, a -$105 billion loss would wipe it out.

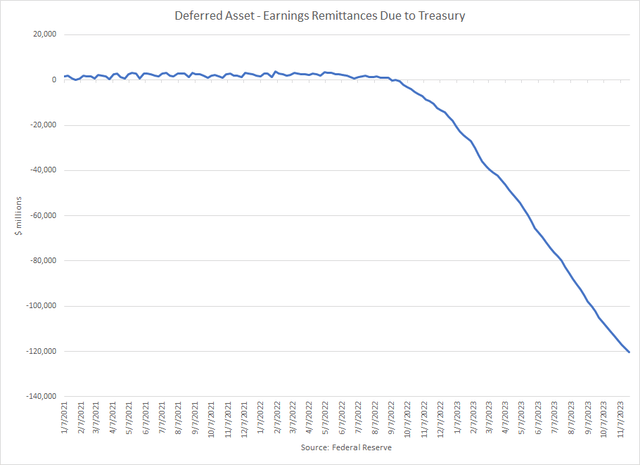

To hinder that from happening, FAM created a new account called “Deferred Asset – Remittances to the Treasury.”

The Deferred Asset account is a plug account on the balance sheet, that prevents the operating loss from impacting the Fed’s capital. Using the Fed’s lenient accounting procedure, Voila! – they turn an operating loss into an asset. In effect, they are hiding the loss.

An asset, by definition, is something of value. The Fed’s Deferred Asset, however, doesn’t really fit that description. It can’t be sold, nor does it contribute to how the Fed runs its operations.

Deferred Asset Account

The Fed’s operating losses are expected to remain for quite some time. According to the Fed’s own estimates, the deferred asset account will continue to grow through 2025.

As of the Fed’s most recent weekly H.4.1 Factors Affecting Reserve Balances report, dated 11/24/23, the deferred asset account has expanded to a cumulative loss of $120 billion.

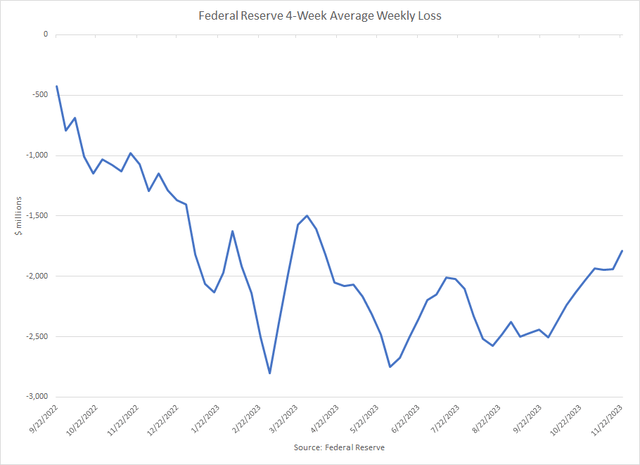

There has been some improvement, though. As the Fed has reduced the size of their balance sheet through Quantitative Tightening (QT), their asset/liability mismatch has narrowed. The Fed’s 4-week average weekly loss has declined to -$1.8 billion from a peak of -$2.8 billion in March 2023.

Once the Fed returns to earning a profit, the positive net income will be used to pay down the value of the deferred asset until it reaches zero. At that point, the Fed will resume sending remittances to the Treasury. The Fed has estimated that remittances to the Treasury will not begin until 2029.

Looking at the Footnotes

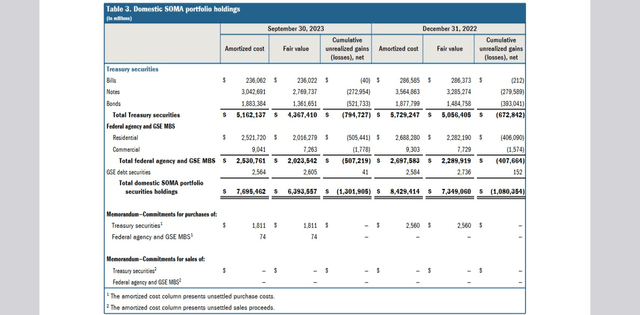

The largest component of the Fed’s balance sheet is their bond holdings. At 3Q23 they own $5.2 trillion of US Treasury notes and $2.5 trillion of MBS. These positions are held in the System Open Market Account (SOMA) and they are carried at amortized cost. Combined, the $7.7 trillion SOMA portfolio represents 95% of the Fed’s total assets.

For those willing to delve a bit deeper into the footnotes, they will find something quite revelatory.

In Footnote 2, Table 3, they converse the SOMA portfolio holdings. While on the balance sheet they are carried at Amortized Cost, in this footnote the securities are shown additionally at Fair Value, or Market Value.

What is clear, is that the Market Value for the portfolio is significantly lower. The unrealized loss for the SOMA portfolio totals $1.3 trillion!

This represents a 16.8% loss in value from when the bonds were purchased.

Under QT, the Fed has been targeting reducing their balance sheet by $95 billion per month, and they have been managing this shrinkage through maturity roll-offs. They have not been able to face their monthly targets, though, because they don’t have enough securities maturing each month, especially from the MBS positions.

If they were to sell MBS to face the QT targets, they would have to recognize losses, and they do not want to add to their already large operating loss position. Hence, QT will continue at its below target pace.

Implications

The Fed has stated that:

“while the rising interest rates have ancillary effects for the Federal Reserve’s income and the unrealized position of the SOMA portfolio, none of these effects impair the Fed’s ability to conduct monetary policy or to accomplish any of its other responsibilities.”

While this is true in the short run, the longer-run implications are not known.

The Fed has not publicly discussed their operating losses, although there has been brief cite, in an opaque way, buried deep in the minutes of the FOMC meetings. Fed Chairman Jay Powell has held 9 press conferences following FOMC meeting since the operating losses began, and he has never been questioned by reporters about the losses.

The Fed outwardly seems to not be concerned with their operating loss and their unrealized portfolio loss. If this is true, then they have no disincentive for taking undue risks. Let’s not neglect that the reason they are in this current position is because they changed their historical method of conducting monetary policy during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, and put risk back on their balance sheet. (For a fuller discussion please see my Seeking Alpha article “The Fed Has A Problem” here.)

By the Fed creating their own accounting rules, instead of from an independent organization, they are essentially policing themselves. History has shown that this does not guide to good outcomes.

Whether the Fed is concerned, or not, their losses are large and significant.

This year, for the first time ever, the Fed will not make a remittance to the Treasury. The Treasury, therefore will have to come up with additional revenue to make up for the Fed’s losses. Ultimately, this burden will fall on the taxpayers.

When the magnitude of the Fed’s losses become more widely known, there will be pressure from congress to curb the Fed’s independence. There are already some early rumblings on this front.

Finally, the Fed risks losing the confidence of the public, that they are capable of being the backstop to financial crises. Confidence comes from strength, and the Fed is financially the weakest now that they have ever been.

As Professor Knutson taught, one must scrutinize a financial report to learn the true workings of the entity.