The number of fixed-rate energy deals on the market is still low – and most work out as the most expensive way to power a home.

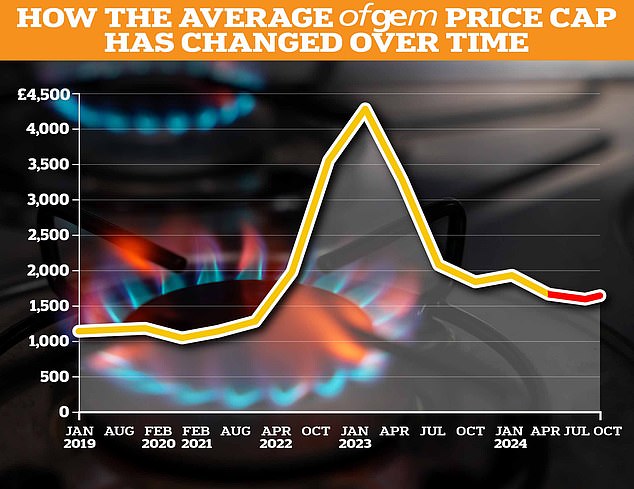

UK households are currently paying typical energy bills of £1,928 a year – the average amount paid for gas and electricity for a variable-rate deal limited by the Ofgem price cap.

The only hope of paying less than that is finding a cheaper fixed-rate deal, which were once the most common type of energy tariff but have now almost dried up.

Although fixed-rate energy deals are coming back, the latest figures from Ofgem and Cornwall Insight show that these tariffs remain scarce – and expensive.

Fix up: The number of fixed energy tariffs is slowly climbing, data shows

Figures on the number of fixed-rate deals are hard to come by.

But energy analysts at Cornwall Insight told This is Money there are currently just 27 such deals available for new and existing customers, with an additional five for existing customers only – a total of 32.

That is a small rise on the 28 fixes available in December 2023 (five for existing customers) and 26 in November 2023 (six for existing customers).

Most fixed-rate energy tariffs are also still expensive, offering little incentive for customers to leave variable-rate deals.

Ofgem said the average fixed rate energy deal cost exactly £100 a year more than a price-capped tariff in November 2023, according to its latest figures.

However, some energy fixes are cheaper than price-capped ones.

The cheapest fixed-rate tariff on the market now with no strings attached costs £1,804 a year, from Home Energy.

That is £104 a year cheaper than a price-capped deal, for average energy use.

The absolute cheapest fix is £1,757 a year, from Ovo, £171 a year cheaper than a price-capped tariff. However, this deal also requires customers to take out boiler cover through the energy firm.

Richard Neudegg, director of regulation at Uswitch, said: ‘There are more fixed deals available now, than this time last year when there were barely any. Yet there is still significantly less than before the energy crisis, when the energy firms would often offer multiple fixed options.

‘Some fixed deals are only available to existing customers but there are some open to new customers, which gives households looking for price certainty some choice over their energy tariff. More still needs to be done to encourage suppliers to bring attractive deals to the market.’

How can I tell if a fixed will save me money?

To work out if an energy deal – fixed or otherwise – is cheaper than you are paying now, compare the unit rate and standing charge with what you currently pay.

The average home is paying rates limited by the Ofgem price cap, which means 53p a day in electricity standing charges and 30p for gas, while electricity unit rates are 29p per kilowatt-hour (kWh) and 7p/kWh for gas.

The massive variable is what happens with the Ofgem price cap in the future. It might be possible to lock into a cheaper deal now, only to see the price cap fall significantly, leaving you overpaying.

When will cheaper energy deals come back?

It is unlikely that many more fixed rates will launch in the near future, or that they will be that cheap.

Cornwall Insight analyst James Mabey said: ‘We do not expect there to be a substantial rise in fixed tariffs over the next few months.

‘Despite wholesale prices easing relatively through the latter part of 2023, the Market Stabilisation Charge (MSC) is still in play, and has risen steadily since December, meaning there remains a financial risk for suppliers to offer fixed tariffs that are at a price position likely to significantly turn the dial.’

The MSC means no energy firm is likely to bring out fixed-rate deals that seriously undercut their rivals, as this would mean they gain customers but risk losing money by having to compensate their opponents if wholesale prices fall.

As the name suggests, the point of the MSC is that it stabilises the market by stopping one energy firm coming out with very cheap deal and causing the others to fail.

The MSC ends on 31 March 2024.

Another Ofgem policy that is holding back the launch of more fixed rates is the ban on acquisition-only tariffs (BAT), Mabey added.

This is an Ofgem policy which stops energy firms offering cheaper deals to new customers, unless they offer these prices to their current customers as well.

Like the MSC, Ofgem brought this policy in in April 2022 to stop one energy firm drastically undercutting its rivals at a time of great turmoil for energy firms.

Mabey said: ‘Ofgem has confirmed that the MSC will expire on 31 March, while the future of the BAT remains unclear, with the regulator considering whether to extend the measure past 31 March.’

Neudegg added: ‘The energy price cap for standard plans is predicted to fall in April, yet we’ll need to wait until February for Ofgem to confirm.

‘We would expect declining wholesale energy rates to also flow into more competitive pricing for fixed deals too, but there are regulations in place that are holding back competition.

‘Ofgem needs to do more to encourage suppliers to offer competitively priced deals. We would like to see providers be innovative with their tariffs to create genuine points of difference to give consumers many more options.’

Why are there so few fixed-rate energy deals?

Energy companies have been slow to bring fixed-rate deals back onto the market.

The problem began when wholesale energy prices began spiking in late 2021. At the time, most households had fixed-rate tariffs, where they locked in to a unit rate and daily standing charge.

This applied regardless of how much their energy firm was buying gas and electricity for at the time – a delicate balance.

So when wholesale energy prices began to rocket this presented a big problem for gas and electricity firms, many of whom were stuck buying energy at far more than the price they were selling it for to consumers.

In response, many energy firms collapsed. At its peak the UK once had 70 different energy providers, in June 2018, but that has now fallen to 21, according to Ofgem figures.

Energy firms also began hiking the price of fixed-rate deals in August 2021, and by September 2022 there were no fixes available for new customers at all.

These fixed-rate deals began trickling back onto the market from June 2023, but have remained low in number and high in price.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money, and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.