For most retirees, their monthly Social Security income is indispensable. Based on more than two decades of annual surveys from national pollster Gallup, no fewer than 80% of retired respondents have relied on their Social Security check, in some capacity, to make ends meet in a given year.

Given how important Social Security is to the financial well-being of our nation’s aging workforce, you’d think maintaining a strong foundation would be a top priority. However, America’s top retirement program is facing a long-term funding shortfall that continues to widen with almost every passing year.

Image source: Getty Images.

Social Security is staring down a $22.4 trillion cash shortfall

For more than eight decades, the Social Security Board of Trustees has released an annual report detailing the financial health of America’s leading retirement program. This report also takes into account a myriad of demographic changes, as well as fiscal and monetary policy shifts, to forecast Social Security’s solvency 10 years (the “short term”) and 75 years (the “long term”) into the future.

The good news is that Social Security is in no danger of going bankrupt or becoming insolvent by the time you retire. Approximately 90% of the revenue collected by Social Security derives from the 12.4% payroll tax on earned income (wages and salaries, but not investment income). As long as Americans continue to work and pay their taxes, the Social Security Administration (SSA) will have cash to disburse benefits to those who are eligible.

What may not be sustainable is the current payout schedule, including cost-of-living adjustments. Based on estimates from the 2023 Trustees Report, the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund could exhaust its asset reserves by 2033. Should this occur, sweeping benefit cuts of up to 23% may be necessary for retired workers and survivors of deceased workers.

On a broader scale, the Trustees estimate Social Security is staring down a $22.4 trillion funding shortfall through 2097. If this shortfall isn’t rectified, sweeping benefit cuts would be the expectation.

Did lawmakers steal from Social Security and create this funding problem?

There is no shortage of theories as to why Social Security is facing a growing cash shortfall. But one of the more popular viewpoints online is that America’s top retirement program has been done in by its own lawmakers. Specifically, there’s the belief that Congress pilfered Social Security’s trust funds (the OASI and Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund), which has weakened the financial health of the program.

While this is a pretty popular online thesis — if you don’t believe me, feel free to check the comment section of any Social Security article published online — it lacks one key component: truth.

When the Social Security Act was signed into law in 1935, it contained provisions that outlined what would happen to any excess revenue taken in by the program (i.e., any money collected above and beyond what’s disbursed to eligible beneficiaries and used via administrative expenses to run the Social Security program). The law requires Social Security’s asset reserves to be invested in interest-bearing special issue bonds. This also includes certificates of indebtedness.

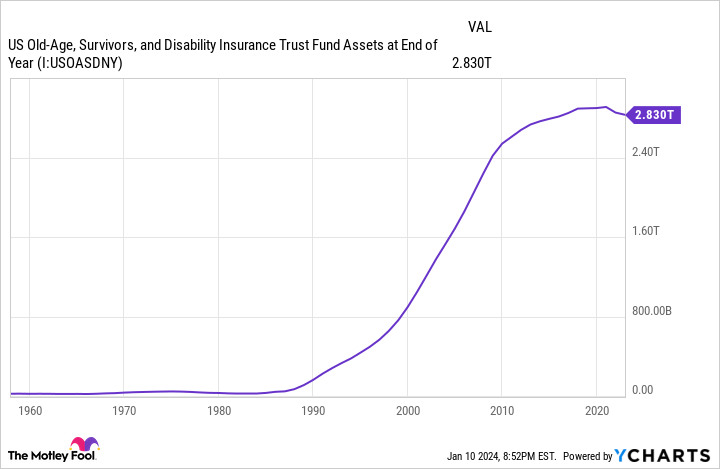

US Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance Trust Fund Assets at End of Year data by YCharts. Data as of Dec. 31, 2022.

Put another way, Social Security’s excess cash isn’t collecting dust in a vault. As of the end of November 2023, the OASI and DI trust funds had a combined $2.77 trillion in asset reserves invested in special issue bonds and, to a far lesser extent, certificates of indebtedness. This $2.77 trillion, which is invested in a multitude of bonds with various interest rates and maturities, sports an average interest rate of 2.436%. The SSA publicly updates the OASI and DI investment holdings monthly, as well as provides a detailed breakdown, based on maturities, annually in the Trustees Report.

Every single cent of Social Security’s asset reserves is accounted for via special-issue bonds and certificates of indebtedness. Remember, these are debt securities backed by the full faith of the U.S. government.

Furthermore, the interest income Social Security is being paid by the U.S. government is one of its three funding sources. Putting aside the fact that investing the program’s asset reserves in special-issue bonds is required by law, having excess reserves collect dust in a vault would cost an already cash-strapped retirement program an estimated $67 billion in annual interest income. In other words, Social Security would be in considerably worse financial shape if its asset reserves weren’t invested in super-safe government bonds.

To sum it up, Congress hasn’t stolen a dime from Social Security; every cent in asset reserves is accounted for; and the program is generating interest income on its excess cash.

Image source: Getty Images.

Here’s what’s really wrong with Social Security

The $22.4 trillion dollar question is: If Congress hasn’t stolen from Social Security, how did America’s top retirement program get into this situation?

The answer primarily lies with ongoing demographic shifts, along with some blame to lawmakers — albeit for a completely different reason than described above.

Some demographic changes are well known, such as the steady retirement of baby boomers. As more boomers leave the workforce, there simply aren’t enough new workers entering the labor force to keep the worker-to-beneficiary ratio from declining.

Life expectancy has also grown by approximately 13 years since the first Social Security benefit check was mailed out 84 years ago. Social Security was never intended to dole out payments to a majority of seniors for multiple decades.

But it’s the less visible demographic shifts that are really taking a toll on Social Security. For instance, legal net migration into the U.S. has been precipitously declining for 25 years. Immigrants coming to the U.S. tend to be younger, which means they’ll spend decades in the labor force contributing to Social Security via the payroll tax. A lack of legal immigration is a big problem.

At the same time, U.S. birth rates have fallen to historic lows. Couples are waiting longer to get married and have children than ever before. Additionally, economic factors, such as rising home prices and short-term economic uncertainty, have encouraged couples to hold off on having children. Lower birth rates would be expected to adversely impact the worker-to-beneficiary ratio in generations to come.

Rising income inequality is another problem for Social Security. In 1984, 91% of all earned income was subject to Social Security’s payroll tax. But as of 2021, only 81% of earned income was exposed to the payroll tax. In other words, a larger percentage of income for high earners is escaping the payroll tax over time.

In addition to demographic shifts, lawmakers do deserve some blame. The inability of Republicans and Democrats to find a common-ground solution to strengthen Social Security has made a future fix all the more difficult.

There’s no question Social Security has a challenging road ahead. However, beneficiaries don’t have to concern themselves with the whereabouts of the program’s asset reserves.