Boy Wirat

In my last post, I looked at equities in 2023 and argued that while they did well during 2023, the bounce back was uneven, with a few big winning companies and sectors, and a significant number of companies not partaking in the recovery. In this post, I look at interest rates, both in the government and corporate markets, and note that while there was little change in levels, especially at the long end of the maturity spectrum, that lack of change called into question conventional market wisdom about interest rates, and in particular, the notions that the Fed sets interest rates and that an inverted yield curve is a surefire predictor of a recession. As we start 2024, the interest rate prognosticators who misread the bond markets so badly in 2023 are back to making their 2024 forecasts, and they show no evidence of having learned any lessons from the last year.

Government Bond/Bill Rates in 2023

I will start by looking at government bond rates across the world, with an emphasis on US treasuries, which suffered their worst year in history in 2022, down close to 20% for the year, as interest rates surged. That same phenomenon played out in other currencies, as government bond rates rose in Europe and Asia during the year, ravaging bond markets globally.

US Treasuries

Investors in US treasuries, especially in the longer maturities, came into 2023, bruised and beaten rising inflation and interest rates. The consensus view at the start of the year was that US treasury rates would continue to rise, with the rationale being that the Federal Reserve was still focused on knocking inflation down, and would raise rates during the year. Implicit in this view was the belief that it was the Fed that had created bond market carnage in 2022, and in my post on interest rates at the start of 2023, I took issue with this contention, arguing that it was inflation that was the culprit.

1. A Ride to Nowhere – US Treasury Rates in 2023

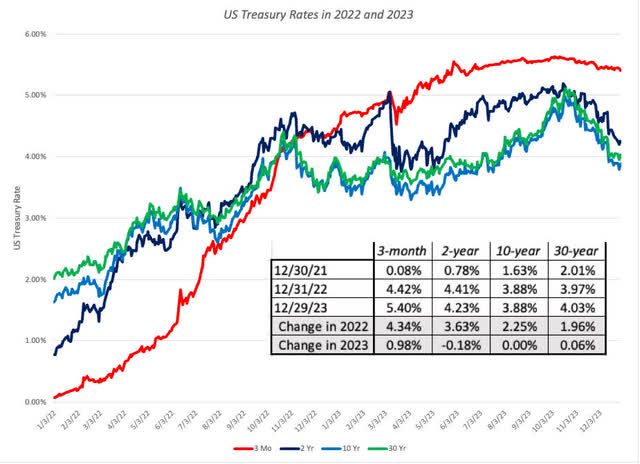

It was undoubtedly a relief for bond market investors to see US treasury markets settle down in 2023, though there were bouts of volatility, during the course of the year. The graph below looks at US treasury rates, for maturities ranging from 3 months to 30 years, during the course of 2022 and 2023:

As you can see, while treasury rates, across maturities, jumped dramatically in 2022, their behavior diverged in 2023. At the short end of the spectrum, the three-month treasury bill rate rose from 4.42% to 5.40% during the year, but the 2-year rate decreased slightly from 4.41% to 4.23%, the ten-year rate stayed unchanged at 3.88% and the thirty-year rate barely budged, going from 3.76% to 4.03%. The fact that the treasury bond rate was 3.88% at both the start and the end of the year effectively also meant that the return on a ten-year treasury bond during 2023 was just the coupon rate of 3.88% (and no price change).

2. The Fed Effect: Where’s the beef?

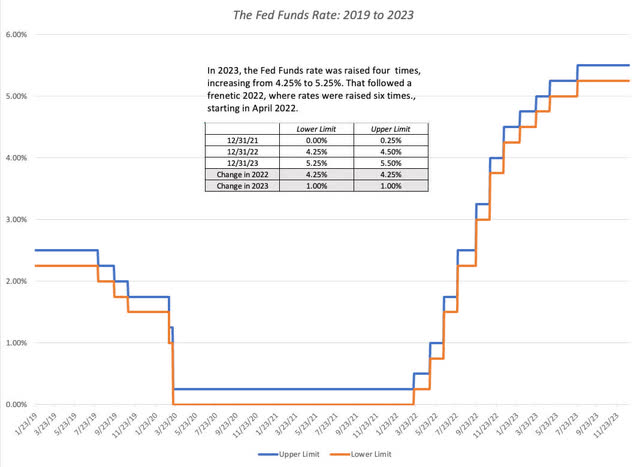

I noted at the start of this post that the stock answer that most analysts and investors when asked why treasury rates rose or fell during much of the last decade has been “The Fed did it”. Not only is that lazy rationalization, but it is just not true, and for many reasons. First, the only rate that the Fed actually controls is the Fed funds rate, and it is true that the Fed has been actively raising that rate in the last two years, as you can see in the graph below:

In 2022, the Fed raised the Fed funds rate seven times, with the rate rising from close to zero (a lower limit of zero and an upper limit of 0.25%) to 4.25-4.50%, by the end of the year. During 2023, the Fed continued to raise rates, albeit at a slower rate, with four 0.25% raises.

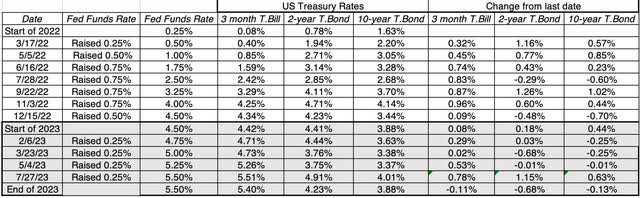

Second, the argument that the Fed’s Fed Funds rate actions have triggered increases in interest rates in the last two years becomes shaky, when you take a closer look at the data. In the table below, I look at all of the Fed Fund hikes in the last two years, looking at the changes in 3-month, 2-year, and 10-year rates leading into the Fed actions. Thus, the Fed raised the Fed Funds rate on June 16, 2022, by 0.75%, to 1.75%, but the 3-month treasury bill rate had already risen by 0.74% in the weeks prior to the Fed hike, to 1.59%.

In fact, treasury bill rates consistently rise ahead of the Fed’s actions over the two years. This may be my biases talking, but to me, it looks like it is the market that is leading the Fed, rather than the other way around.

Third, even if you are a believer that the Fed has a strong influence on rates, that effect is strongest on the shortest-term rates and decays as you get to longer maturities. In 2023, for instance, for all of the stories about the FOMC meeting and the Fed raising rates, the two-year treasury declined and the ten-year did not budge. To understand what causes long-term interest rates to move, I went back to my interest rate basics, and in particular, the Fisher equation breakdown of a nominal interest rate (like the US ten-year treasury rate) into expected inflation and an expected real interest rate:

Nominal Interest Rate = Expected Inflation + Expected real interest rate

If you are willing to assume that the expected real interest rate should converge on the growth rate in the real economy in the long term, you can estimate what I call an intrinsic risk-free rate:

Intrinsic Riskfree Rate = Expected Inflation + Expected real growth rate in economy

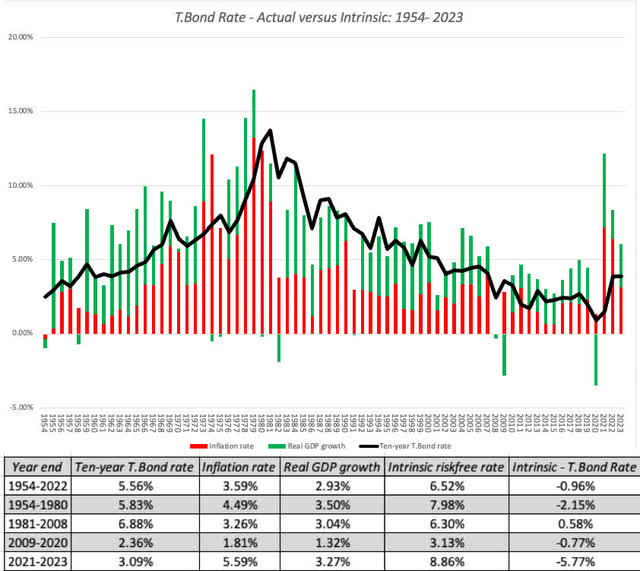

In the graph below, I take the first shot at estimating this intrinsic risk-free rate, by adding the actual inflation rate each year to the real GDP growth rate in that year, for the US:

I will not oversell this graph, since my assumption about real growth equating to real interest rates is up for debate, and I am using actual inflation and growth, rather than expectations. That said, it is remarkable how well the equation does at explaining the movements in the ten-year US treasury bond rate over time. The rise of treasury bond rates in the 1970s can be clearly traced to higher inflation, and the low treasury bond rates of the last decade had far more to do with low inflation and growth, than with the Fed. In 2023, the story of the year was that inflation tapered off during the course of the year, setting to rest fears that it would stay at the elevated levels of 2022. That explains why US treasury rates stayed unchanged, even when the Fed raised the Fed Funds rate, though the 3-month rate remains a testimonial to the Fed’s power to affect short-term rates.

3. Yield Curves and Economic Growth

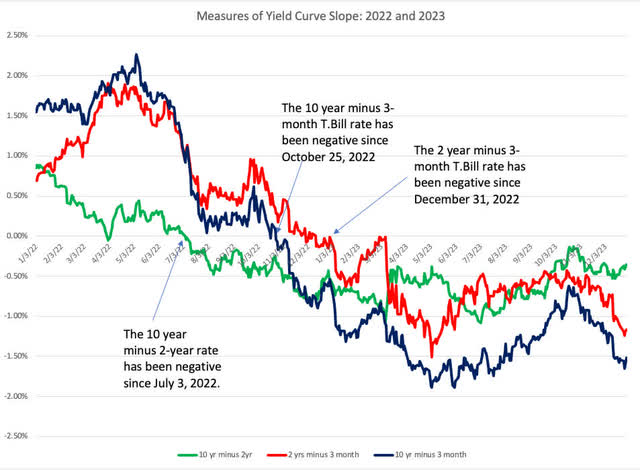

It is undeniable that the slope of the yield curve, in the US, has been correlated with economic growth, with more upward-sloping yield curves presaging higher real growth, for much of the last century. In an extension of this empirical reality, an inversion of the yield curve, with short-term rates exceeding long-term rates, has become a sign of an impending recession. In a post a few years ago, I argued that if the slope of the yield curve is a signal, it is one with a great deal of noise (error in prediction). If you are a skeptic about the inverted yield curves as a recession predictor, that skepticism was strengthened in 2022 and 2023:

As you can see, the yield curve has been inverted for all of 2023, in all of its variations (the difference between the ten-year and two-year rates, the difference between the two-year rate and the 3-month rate, and the difference between the ten-year rate and the 3-month T.Bill rate). At the same time, not only has a recession not made its presence felt, but the economy showed signs of strengthening towards the end of the year. It is entirely possible that there will be a recession in 2024 or even in 2025, but what good is a signal that is two or three years ahead of what it is signaling?

Other Currencies

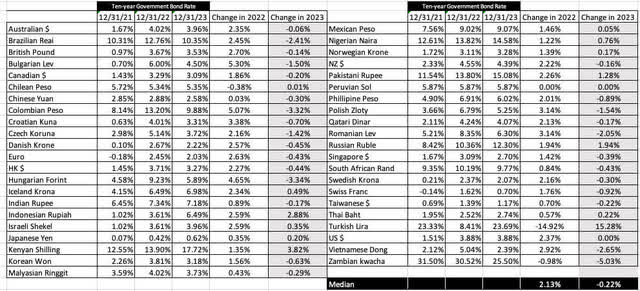

The rise in interest rates that I chronicled for the United States played out in other currencies, as well. While not all governments issue local-currency bonds, and only a subset of these are widely traded, there is information nevertheless in a comparison of these traded government bond rates across time:

Note that these are all local-currency ten-year bonds issued by the governments in question, with the German Euro bond rate standing in as the Euro government bond rate. Note also that during 2022 and 2023, the movements in these government bond rates mimic the US treasuries, rising strongly in 2022 and declining or staying stable in 2023.

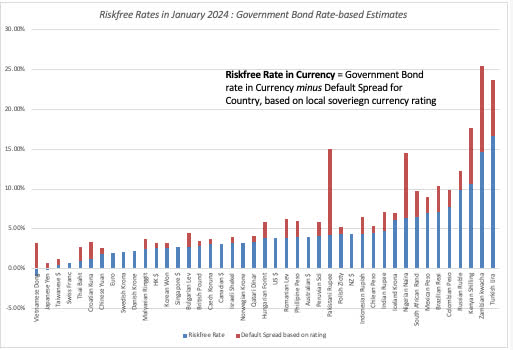

These government bond rates become the basis for estimating risk-free rates in these currencies, essential inputs if you are valuing your company or doing a local-currency project analysis; to value a company in Indian rupees, you need a rupee riskfree rate, and to do a project analysis in Japanese yen, a riskfree rate in yen is necessary. While there are some who use these government bond rates as risk-free rates, it is worth remembering that governments can and sometimes do default, even on local currency bonds, and that these government bond rates contain a spread for default risk. I use the sovereign ratings for countries to estimate and clean up for that default risk, and estimate the riskfree rates in different currencies at the start of 2024:

Unlike the start of 2022, when five currencies (including the euro) had negative risk-free rates, there are only two currencies in that column at the start of 2024; the Japanese yen, a habitual member of the low or negative interest rate club, and the Vietnamese Dong, where the result may be an artifact of an artificially low government bond rate (lightly traded). Understanding that risk-free rates vary across currencies primarily because of differences in inflation expectations is the first step to sanity in dealing with currencies in corporate finance and valuation.

Corporate Borrowing

As risk-free rates fluctuate, they affect the rates at which private businesses can borrow money. Since no company or business can print money to pay off its debt, there is always default risk, when you lend to a company, and to protect yourself as a lender, it behooves you to charge a default or credit spread to cover that risk:

Cost of borrowing for a company = Risk-free Rate + Default Spread

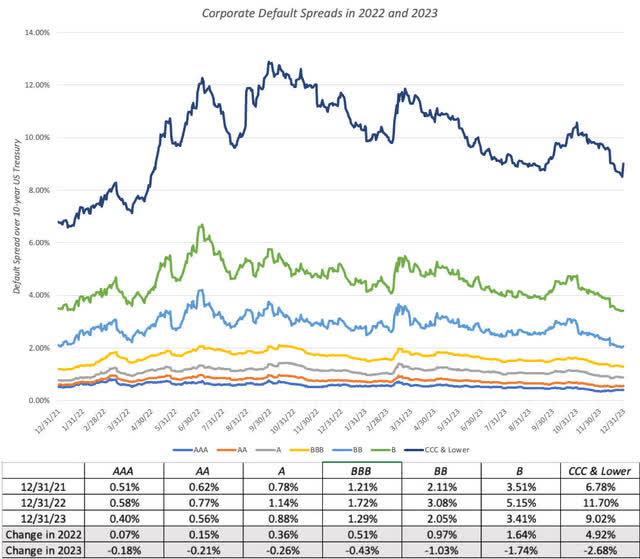

The question, when faced with estimating the cost of debt or borrowing for a company, is working out what that spread should be for the company in question. Many US companies have their default risk assessed by rating agencies (Moody’s, S&P, Fitch), and this practice is spreading to other markets as well. The bond rating for a company then becomes a proxy for its default risk, and the default spread then becomes the typical spread that investors are charging for bonds with that rating. In the graph below, I look at the path followed by bonds in different rating classes – AAA, AA, A, BBB, BB, B, and CCC & below – in 2022 and 2023:

As with US treasuries, the default spread behaved very differently in 2023, as opposed to 2022. In 2022, the spreads rose strongly across rating classes, and more so for the lowest ratings, over the course of the year. During 2023, default spreads reversed course, declining across the rating classes, with larger drops again in the lowest rating classes.

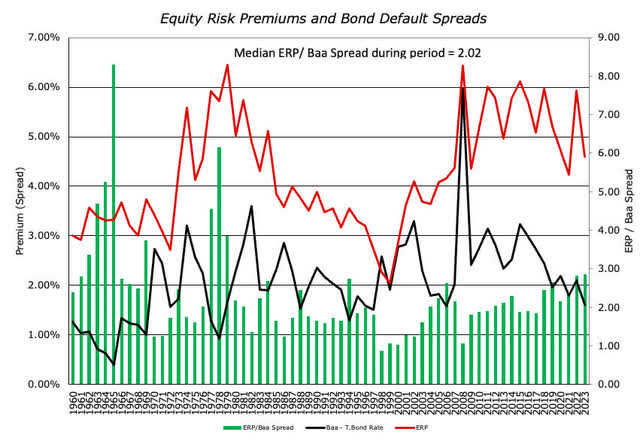

One perspective that may help make sense of default spread changes over time is to think of the default spread as the price of risk in the bond market, with changes reflecting the ebbs and flows of fear in the market. In my last data update, I measured the price of risk in the equity market in the form of an implied equity risk premium and chronicled how it rose sharply in 2022 and dropped in 2023, paralleling the movements in default spreads. The fact that fear and risk premiums in equity and bond markets move in tandem should come as no surprise, and the graph below looks at the equity risk premiums and default spreads on one rating (BAA) between 1928 and 2023:

For the most part, equity risk premiums and default spreads move together, but there have been periods where the two have diverged; the late 1990s, when equity risk premiums plummeted while default spreads stayed high, preceding the dot-com crash in 2001, and the the 2003-2007 time periods, where default spreads dropped but equity risk premiums stayed elevated, ahead of the 2008 market crisis. Consequently, it is comforting that the relationship between the equity risk premium and the default spread at the start of 2024 is close to historic norms and that they have moved largely together for the last two years.

Looking to 2024

If there are lessons that can be learned from interest rate movements in 2022 and 2023, it is that notwithstanding all of the happy talk of the Fed cutting rates in the year to come, it is inflation that will again determine what will happen to interest rates, especially at the longer maturities, in 2024. If inflation continues its downward path, it is likely that we will see longer-term rates drift downwards, though it would have to be accompanied by a significant weakening in the economy for rates to approach levels that we became used to, during the last decade. If inflation persists or rises, interest rates will rise, no matter what the Fed does.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.