You’d be forgiven for thinking the energy market had finally turned a corner.

Ofgem’s price cap fell at the start of the month, wholesale prices have started to somewhat stabilise and there has been a quiet return of the fixed price tariff.

It might hark back to a more ‘normal’ market, but it is one that has fundamentally changed and is now very much a product of the energy crisis.

With so many suppliers going bust two years ago, the big legacy suppliers have come to dominate once more and attention has turned to what they’re really offering customers.

Competition hots up: Experts say energy suppliers will continue to fight for customers without cut-price deals

Wholesale prices have been on a downward trajectory but remain much higher than pre-crisis and pandemic levels, and this is unlikely to change soon.

It means that suppliers are having to increasingly compete in new territory: price is no longer everything and customers are looking for more from their suppliers.

Additionally, the once plucky upstart Octopus Energy has taken the market by storm and the recent acquisition of Shell Energy customers could shake-up the market further as it vies for the top spot.

We look at why customers will struggle to find cheap deals across variable and fixed tariffs, where suppliers might start to compete instead and whether Octopus could realistically take take spot.

Why big 6 suppliers dominate the market again

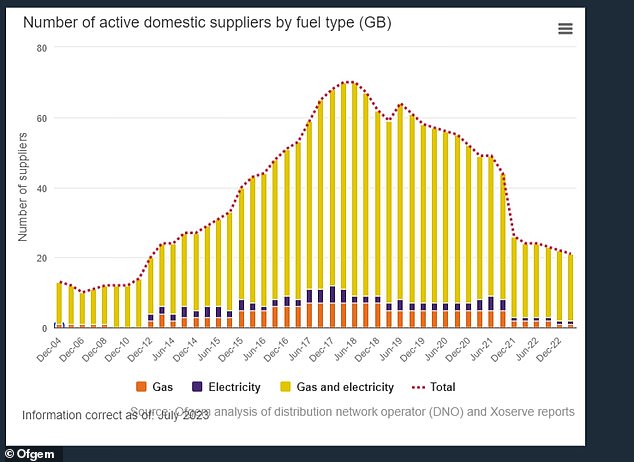

Two years ago, there were 44 active domestic suppliers in Britain, down from a peak of 70 in 2018. Now, there are just 20.

Smaller suppliers flooded the market and consumers paid less as they shopped around for cut-price deals, avoiding the higher prices consumers who didn’t switch regularly were paying.

But when wholesale energy costs soared in 2021, a number of suppliers, including Bulb Energy which had 4million customers, they became the victim of their own success.

Martin Young, utilities equity analyst at Investec, told This Is Money: ‘There was clearly a desire by politicians and, by extension, Ofgem to see competition as a barometer of success. It was competition for competition’s sake. The levels that people were pricing was unsustainable.

‘Having 70-plus suppliers in the energy market… you don’t need that to have a competitive market, as proved by the collapse of many of those suppliers.’

Fewer suppliers means there is less of a need for suppliers to compete and now hamstrung by wholesale costs, there is no need for the cut-price deals we saw before the crisis.

Additionally, millions of customers who were with smaller firms that went bust were put onto Ofgem’s supplier of last resort regime, further bolstering bigger suppliers’ customer bases.

The fallout from the collapse of so many firms pushed Ofgem to do more around the financial requirements for suppliers.

It means there is a higher barrier to entry and ongoing participation than there was before, says Young and ‘that’s another reason why I don’t think we’re going to see cut-price deals.’

The shakedown of suppliers left a group of ‘more sensible’ suppliers who are unlikely to offer such unsustainable pricing.

Why are fixed price tariffs so uncompetitive?

Suppliers started to quietly reintroduce fixed tariffs for its customers following a fall in the October price cap.

A look at the tariffs on offer show very few that are remotely competitive with the price cap, but are still a move in the right direction.

Most fall just below or just above it so for those who don’t need the security of knowing how much they’ll pay for their energy in the coming months, there’s little point in switching.

Wholesale prices had started to fall when the tariffs were introduced, so why are they so uncompetitive?

Depending on whether or not you think prices are set to rise again in January – as energy experts Cornwall Insight do – the tariffs might offer you a good deal.

The reason they might seem uncompetitive is because of market volatility and suppliers are likely hedging their bets. But it’s also partly to do with how the energy price cap is calculated.

We now have quarterly updates of the price cap, rather than every six months, which Young says means it is more representative of the current market than it was in the past.

‘When wholesale prices were going up, the cap was the cheapest place to be. That’s why for a lot of people, when they got to the end of their existing fixed price deals, basically said ‘what’s the cheapest energy bill? It’s to go on the cap’. That’s why the SVT numbers went up significantly.

‘Given that the energy cap is more in real-time, that’s why we’re less likely to see fixed price deals that are significantly away from where the cap sits, because of the frequency of updating the cap.’

Ultimately, with wholesale prices still well above pre-crisis levels, there is very little suppliers can do on price.

And there’s little chance of any supplier diverging from the price cap, especially with fewer challenger suppliers vying for a portion of their customer base.

Gareth Kloet, energy expert at GoCompare told This Is Money: ‘We’re not in control of that price point and if things start to get more uncertain with energy in the future, that would force prices upward.

‘No one can really control that. The energy regulator has the cap but they ultimately have to respond to what’s happening in the market.’

| Company | Market Share Q1 2004 electricity | Market Share Q1 2004 gas | Company | Market Share Q1 2023 electricity | Market Share Q1 2023 gas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Gas | 24% | 55.8% | British Gas | 20.4% | 28.2% |

| E.On | 21% | 12.4% | E.On | 17.2% | 14.4% |

| Npower | 15% | 9.2% | Ovo | 13.3% | 11.1% |

| SSE | 14% | 10.1% | EDF | 11.3% | 9.4% |

| EDF | 14% | 4.6% | Octopus | 16.6%* | 16.3%* |

| Scottish Power | 11% | 8.6% | Scottish Power | 8.9% | 7.7% |

| Source: Ofgem *These figures are before the Shell Energy takeover by Octopus. Shell has roughly a 4.5% market share |

|||||

Could Octopus become Britain’s biggest supplier?

Even if suppliers can’t compete on price, it’s very unlikely they’re going to down tools and stop trying to grow their customer numbers.

One significant development has been Octopus Energy’s acquisition of Shell Energy, coming months after its deal to buy Bulb Energy.

Once the deal to buy Shell Energy’s 1.5million customers is completed, Octopus will be in touching distance of British Gas’ position as Britain’s top energy supplier.

Kloet said: ‘Octopus are a real force to be reckoned with now… if Octopus could gain half a million customers off British Gas, I think it would certainly increase competition in the market. Certainly between those two.

Octopus Energy are a real force to be reckoned with

Gareth Kloet, energy expert at GoCompare

‘If I were in charge of British Gas, I’d be making plans to make sure I didn’t lose the top spot. At the moment they’re not doing much more than mirroring the price cap.

‘They’ve got a few months because I would imagine the short term focus for Octopus is completing customer migration from Shell to Octopus, putting them on new tariffs, setting up billing, getting meter readings sorted. But they’ll be looking at how they can get the top spot and entice new customers.’

If suppliers’ hands are tied when it comes to pricing – given the constraints from the energy price cap and higher wholesale prices – they’re more likely to compete on customer service and different tariffs.

Young suggests that the growth of electric vehicles and solar panel installation opens up a new frontier and suppliers will pivot their attention to offering innovative tariffs.

‘EV growth will equal charge point installation growth, and if you’ve got a charger on your wall you probably want some kind of innovative tariff so you can charge your car at a point in the day when it’s likely to be cheaper.

‘You need a supplier who’s willing to offer an innovative tariffs. I expect you’ll get a bit of competition going on in that sphere.’

Kloet thinks suppliers might also consider offering bundles like boiler cover in their tariffs and ‘trying to do something beyond energy to retain customers’.

The most recent Ofgem switching data suggests that even with prices so high, people are continuing to switch.

In July 2023, the total number of switches was up 18 per cent on the previous month, and 96 per cent more than the level in July 2022. It’s still 62 per cent lower than two years ago, but with the colder months approaching and more fixed price tariffs on the market, some more people might be tempted to switch.

‘If you roll them all together – innovative tariffs and customer services – will be the big drivers of change,’ says Young. ‘That group of people will get bigger so there’ll be competition, yes. I think about it in a different way to plain vanilla on price alone.’

Cut-price deals might not be on the cards for households this winter, but the market seems to be heating up again.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money, and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.