TU IS

The history of Constellation Software [CSI] (TSX:CSU:CA) cannot be understood without studying the figure of Mark Leonard, an unconventional entrepreneur within what is commonly understood as a CEO. Leonard studied business in Canada and worked in venture capital for 11 years. Within this world, he realized the existence of a very attractive type of business where there was normally little interest from large investment conglomerates: vertical software. These were generally niche businesses with little growth potential but with recurring and stable revenues. Leonard, knowledgeable about the investment world and the successful history of Berkshire Hathaway, recognized the opportunity and created an idea to acquire vertical software companies as a perpetual owner: Constellation Software. The company was founded in 1995 with $25 million that Mark Leonard raised from various pension funds and investors who financed Constellation’s journey.

Since then, CSI has become a company that generates more than $1 billion in cash flow, employs more than 50,000 people, and has made more than 500 acquisitions throughout its lifetime. In this article, we will analyze it in detail.

VMS

The vertical software business has a series of unit economics that differentiate it from horizontal applications like Microsoft’s functionalities. Firstly, VMS operates in very specific niches where large companies find it challenging to operate. The development cost would be very high (typically, technical personnel tend to develop other types of functions, requiring training expenses), and the potential profit would be low. VMS businesses usually manage millions of dollars in billing, while horizontal software is easily scalable. The revenue from Microsoft Office is currently $36 billion, 6 times higher than the annual sales generated by CSI. A 16% increase in the price of Office 365 subscriptions would generate sales equal to CSI’s revenue. Microsoft has no economic incentives to enter this market. An immediate consequence is that competition is greatly reduced since large companies have no incentives to operate in VMS.

Furthermore, the high degree of specialization required further reduces the chances of competitors entering the market. Lastly, and as a consequence of the previous points, revenues are stable and recurring. However, VMS companies shouldn’t use indiscriminate price increases to boost revenue. Natural monopolies can be broken if the service provider increases the price without increasing the value provided.

Within this market, CSI is willing to acquire companies that meet the following characteristics:

- Operating profits exceeding $1 million (#1 or #2 in market share).

- Consistent and growing profits (over 20%).

- Management team committed to the business.

- Pre-determined selling price.

The virtuous circle of CSI

Most of CSI’s growth is inorganic. This is why acquisitions play a fundamental role in the ecosystem. The CSI acquisition algorithm operates according to the following principles.

1. Different companies in CSI’s operating groups generate free cash flow. This is achieved through a strict business selection policy. They must generate positive profits for an acquisition to take place.

2. The majority of the cash flow generated by subsidiaries is available to CSI, which can be used to make new acquisitions. CSI’s organic growth is at 3%, and most of the growth is acquired.

3. If acquisitions are made at reasonable valuations, the available cash flow increases, allowing positive feedback that returns to point 1.

For the algorithm to continue working satisfactorily, CSI’s operating groups must continue generating profits, and acquisitions to be made at reasonable valuations. A reduction in any of these points would result in lower organic growth or lower return on invested capital. In other words, less value generation for the shareholder.

How is it possible that CSI has sustained such a high-value generation for shareholders for so long? The answer comes next, but CSI’s goal has always been to create a superstructure capable of belonging to Bessembinder’s 4%, a select group of companies that have positively contributed to value generation in the stock markets. Few businesses manage to survive for years while continuing to increase shareholder value. It is a highly challenging task. How things are done and the focus of people in the company will produce one result or another. Over time, CSI has survived and increased its durability thanks to the following points:

Autonomy of operating groups: Allows the selection of the best business models in different operating groups.

Successful business models spread successfully within the company. They will likely survive. When this evolutionary process is underway, there is no need to constantly repeat our values.

Perpetual owner: This is an essential element in CSI’s activities. Unlike a Private Equity group, Constellation seeks to acquire and own VMS companies with a clear horizon: forever. In general, this tends to attract owners who sell their businesses to CSI. They know that within the structure, the survival and well-being of the business and employees will be guaranteed.

Incentivizing meritocracy: Allows a positive selection process for managers/employees. The company increases the salaries of good managers/employees and seeks to retain talent for a long time.

We believe that when we limit the time of a competent director, we limit their opportunity to learn and consequently contribute value… Training and talent selection are where directors can actively contribute to the company adhering to Bessembinder’s 4%. Certainly, we do not want to get rid of them after 10 years in the position.

Beyond certain salary levels, the company requires owning a certain amount of shares. When managers/employees receive bonuses, they are required to invest a portion of CSI’s shares. In 2015, the company had more than a hundred millionaire employees! Mark Leonard’s goal was to increase the number to more than 500 in the following years.

Finance

Once we have understood the CSI Tao, it is necessary to see if the words have translated into actions. That is, has the company evolved as its founder suggests? The answer is yes.

The evolution of the business can be measured in terms of cash flow per share, the real profit that the company possesses after investments, interest, tax payments, and other operating expenses. In addition to cash flow per share, it is of special interest to measure the net value that CSI generates for shareholders. The company operates in the vertical software niche, a market where profits can grow without extraordinary capital requirements. This is why Mark Leonard suggests calculating the net value for shareholders as the sum of return on invested capital (ROIC) and net organic growth. Through this message, the founder of CSI conveys that the sources of CSI’s value generation come through two ways:

- Returns on acquisitions: The majority of the capital that CSI invests is in acquisitions of VMS companies, which increase the corporation’s cash flow. Consequently, a decrease in ROIC would mean that CSI has overpaid for acquisitions or that the businesses it incorporates do not contribute to increasing profits. In my opinion, it is difficult for this to happen due to management’s actions, as hurdle rates are defined, and the companies to be acquired are as well. A decrease in hurdle rates for acquiring larger VMS companies could push ROIC down.

- Net organic growth: Another source of growth is the increase in prices or volume. Normally, CSI is reluctant to raise prices unless there is an increase in services in licenses/maintenance. Historically, it has been possible to achieve organic growth by gaining new customers and expanding into other verticals, a strategy replicated by one of its listed subsidiaries, Topicus. Organic growth is low because the businesses it acquires are quite mature and have less long-term growth capacity.

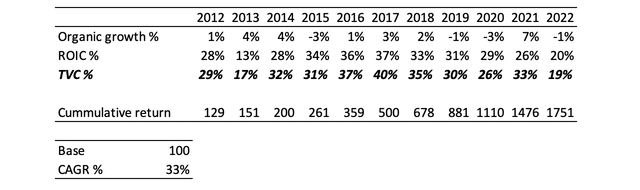

The following table shows the returns on invested capital generated along with the net organic growth of CSI since 2012. The combination of both, as Mark Leonard suggests, is a good proxy for long-term value generation.

Total value creation net for CSI shareholders (Own models)

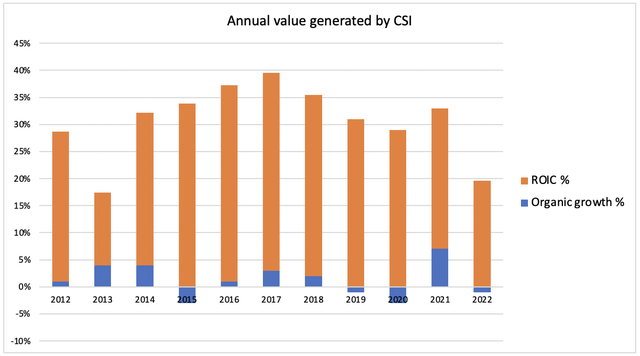

Since 2012, the CSI management team has managed to return 33% in terms of value creation, while the stock has grown by 35%. The market has accurately understood that the two central points are how good they are at acquiring and the organic growth they achieve! However, most of the return is achieved through acquisitions and not organically. Undoubtedly, the future will be determined by how efficient they are in managing capital and acquiring new VMS businesses.

Annual value creation (ROIC + Net organic growth) (Own models)

The future of Constellation

The previous paragraph already mentioned the main risk of the thesis: that CSI may not be able to use the cash flow from operating businesses to achieve more growth and value generation for shareholders. Throughout different letters to shareholders, especially in 2021, Mark Leonard emphasized that he is aware that CSI is at a point where small VMS acquisitions contribute little to the growth of free cash flow. In the last year, CSI has invested $1.5 billion in VMS acquisitions. If it maintains this pace and seeks a 20% return, it would have to acquire $300 million in growth (excluding organic), which seems challenging in small deals. However, this concern has been present for more than 10 years, and the decreasing returns that Mark Leonard himself expected have not occurred. Constellation seems to defy the gravity of financial returns with returns that are never decreasing.

Leonard himself has emphasized that to maintain profitability in the future and fulfill the purpose for which CSI was created (perpetual owner), the culture he established and that has permeated all operating groups must be maintained:

- Continue with the autonomy of operating groups and deepen decentralization.

- Maintain standards regarding the minimum profitability that CSI directors demand from acquisitions.

- Explore new opportunities in large VMS businesses (although they depend on the economic cycle, the minimum is usually around 30-40 annually) whose prices are acceptable to CSI.

- Move away from the VMS world and explore new opportunities in other sectors where unit economics is also attractive.

With all this in mind, the CSI management team always seeks to act as capital stewards, a kind of guardians of shareholders’ capital in search of durability (perpetual owner) and constant value generation. It is important to make emphasize the fact that Leonard, although important, is not supervising day-to-day deals within the different operating groups. The founder of CSI is now close to 70 years old and sooner or later he will have to retire and leave space for the new generations. If the culture that he has taught to the different business units of CSI endures, I believe the company will keep being successful in its strategy in the years to come.

Is there value?

In general, many analyses of CSI often begin by saying: CSI’s multiple is … and it will grow … Consequently, it is expensive, and we must reduce the position. This type of analysis using multiples is not recommended since they capture much more information than future growth. The multiple is a kind of inverse of the discount factor in cash flow. This factor reflects the company’s future growth and other aspects such as the predictability of income, investor confidence in the management team, business durability, and the cost of debt. This is why I prefer to value CSI as Mark Leonard suggests: return on capital % + net organic growth %. In the long run, this will be the return that CSI gives to shareholders. In a conservative scenario, CSI could achieve deals that generate an ROIC of 15% and organic growth of 1% (on average), resulting in a net value generation for shareholders of 16%. In the most optimistic scenario, CSI would be able to maintain returns if the culture remains and the different operating groups continue to make acquisitions without altering the model for an extended time.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.