JuSun

Written by Sam Kovacs.

Introduction

I wrote an article earlier this week titled “Sell Alert: The Slaughter of Office REITs is just beginning.”

What many investors don’t realize is that when I started seriously looking at office real estate investment trusts, or REITs, in October last year, I was doing so with the intention of finding a REIT worth buying.

But deep-rooted problems within the industry, which I highlighted in the article linked above, kept me away from investing in these stocks.

Since June last year, I’ve been increasing my exposure to REITs, and on October 6th, just 20 days before REITs bottomed, I wrote members of our private investing group a piece titled, “The REIT opportunity is still alive and well.”

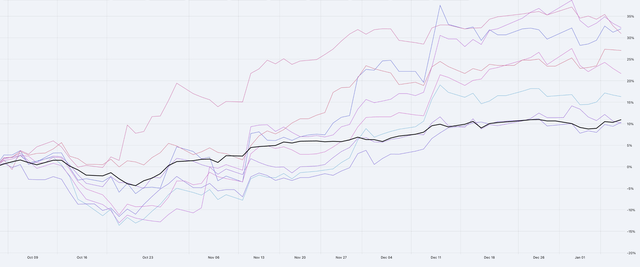

That proved to be timely, as the suggestions we made in that article have performed quite well.

DFT Picks vs SPY (Dividend Freedom Tribe)

So understand that I am not a REIT bear. I believe that in 2024 REITs will do well.

Do not confuse the fed cycle and secular shifts in office demand

But after the year-end REIT rally, I felt compelled to present the information on office REITs to investors for them to not confuse:

- The end of the Fed’s rate hike cycle and its effect on REITs. (bullish)

- The secular shift in demand for offices.

As rates come down, financing costs for REITs will also go down, which is bullish and has pushed all REITs to go up, office REITs included.

It has also led to comments on the previous article like:

Slaughter of office REITS????? Why is the VNO share price so high???????

Let’s not confuse a sector effect with a secular shift which is going to take years.

Of course, investor presentations from office REITs will try and spin the facts to present a compelling narrative.

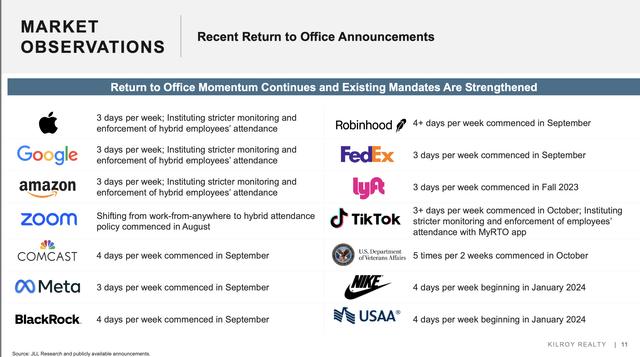

Take the slide from Kilroy Realty Corporation’s (KRC) November presentation:

But all I see from the slide above is that these huge employers which include Apple Inc. (AAPL), Amazon.com, Inc. (AMZN), Meta Platforms, Inc. (META), FedEx Corporation (FDX) and Alphabet Inc. (GOOG) (GOOGL) are mostly expecting 3 days per week from their workers.

And when we look at Kastle Systems index, which looks at the number of access card swipes across 2,600 buildings and 41,000 businesses in the U.S., the return to office has been at best just above 50% of the pre-pandemic numbers.

Looking at the chart gives you the impression that there is progress, but let me tell you, this progress has been slow, and since late 2022 has been extremely slow.

I projected a couple of trend lines on the chart. Returning to 60% of 2019 levels, at the current pace of progress, would take until 2026.

But even if you do get to 60% next year and stay there (assuming a median hybrid 3 days per week at the office), this spells massive trouble for Office REITs.

The demise of Office REITs will be a “slow motion trainwreck” to quote one of the comments in our last article (Thanks @Phil1125 for the great wording).

In the previous article, the main criticism was that I was “late to the game,” that this was “yesterday’s news”, and that this was “fully priced.”

Now note that this is exactly what people were saying about mall REITs before it all came down.

Some things take time. To quote Buffett “you can’t make a baby in one month by getting nine women pregnant.”

One has just to look at the story of rise and fall of malls to understand the parallels happening in office REITs.

So buckle up, because I’m going to take you on a ride through the rise and fall of U.S. malls, to then offer lessons that office REIT investors can learn.

The rise and fall of the U.S. Mall

The birth of the U.S. Mall

After World War 2, a massive wave of births occurred in the U.S.: the baby boom. Four million new children per year, which required new layouts of family infrastructure to emerge.

Two acts, which were passed in 1944, played a crucial role: The GI Bill and the Federal Highway Act.

The former, among other things, allowed returning veterans access to low-cost mortgages, which led to a surge in home ownership. The latter developed a massive network of highways which enabled suburbanization.

More than a million homes each year were built, and the highways linked these newly developed suburban areas to urban cities.

But for all government planning, public policy did not consider central public spaces for Americans.

The focus on homes and roads ignored the need of a so-called “town square” for people to meddle.

And it is in this context that the U.S. mall emerged, not only as a place to sell stuff, but as a symbol of American consumerism.

The first fully enclosed mall opened in 1956 in the suburbs of Minneapolis. A phenomenon had started. By 1960, there were 4,500 malls in the U.S., suggesting 3 per day opened on average since the first opening.

In the 1970s, the invention of the food court brought the malls to the status of “de facto time-square” for the U.S., to quote a Business Insider article.

In the ’70s, 1 out of 3 retail dollars were spent in malls. In the ’80s, it was over 1 in 2.

For half a century, malls enjoyed growth, profitability, and were a sign of the victory of capitalism over communism.

The slow motion trainwreck of the U.S. mall

The advent of the U.S. mall would be given two blows which would send the sector in a downward trend: one which was slow and gradual, and the second which was brutal.

- The first was the advent of ecommerce sales, a slow trend which would develop over years.

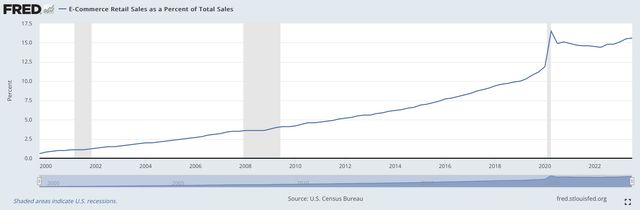

Ecommerce as & of total retail (FRED)

In 2000, ecommerce was 0.8% of retail in the U.S. By 2008, it was 3%. By 2019, it was 11%. Today, it is 15%.

- The second was a singular event: The Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2009.

Now let’s be clear, when the GFC hit, Ecommerce was just a fraction of retail sales and not enough to truly gut malls.

It was reduced discretionary income among Americans which gutted malls, and led to the likes of General Growth Properties (“GGP”) filing for bankruptcy in 2009.

But it created a shift in consumption patterns, with a focus on thriftiness. Ecommerce happened to be a superior method to compare prices from different retailers, with added convenience.

After the recession, certain malls started to recover, but vacancies at a lot of older properties put strain on many malls.

Digital native brands, such as Warby Parker Inc. (WRBY) emerged, focusing on a digital first, direct to consumer model, and Amazon.com, Inc. (AMZN) grew exponentially, further straining malls.

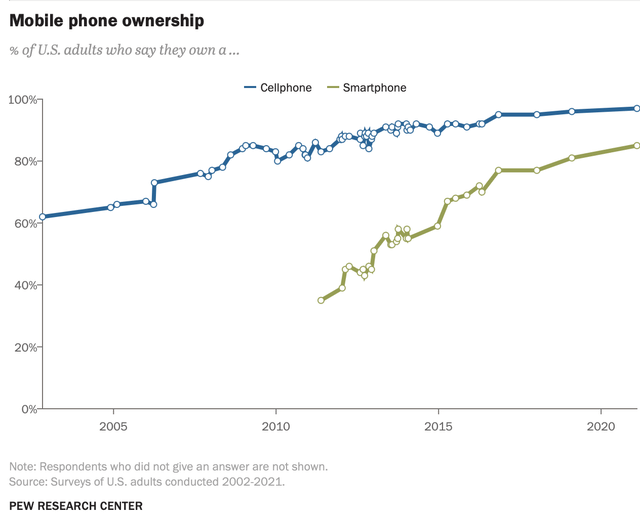

By 2013, half of Americans owned a smartphone, which gave way to mobile shopping.

In 2014 and 2015, there are closures of massive anchor stores like JC Penny and Sears. These leave massive gaps in malls, which are hard to be replaced.

This introduces adaptation methods by malls to introduce experiential retail like theaters, gyms and more to fill the space and attract visitors.

In 2016 and 2017, a record number of brick and mortar stores are closed, as ecommerce finally took enough of a bite out their revenues and profits to make many locations non-viable.

These are the years where we see U.S. mall REIT share prices tumble.

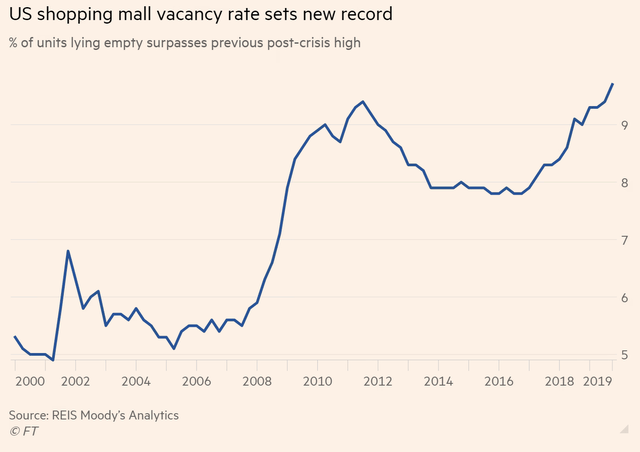

The chart below is a bit dated, but shows that in between 2012 and 2014, there is a slight reduction in vacancies before the industry went into a tailspin.

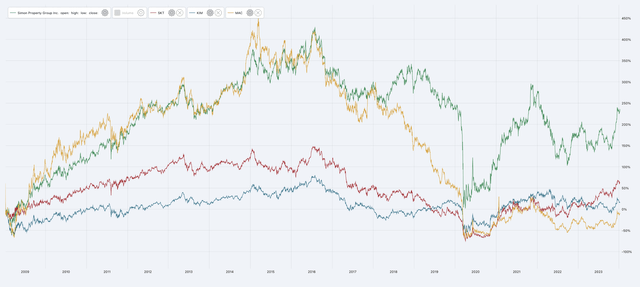

The 15-year chart for a few leading mall stocks shows this:

SPG, SKT, KIM, MAC (Dividend Freedom Tribe)

It includes the following mall REITs:

- Simon Property Group, Inc. (SPG).

- Tanger Inc. (SKT).

- Kimco Realty Corporation (KIM).

- The Macerich Company (MAC).

The mistake made between 2010 and 2014 by mall investors was to confuse a business and market cycle with a secular shift in the way people consume.

Because what one needs to remember is that just as malls were the de facto town square, social media became the de facto town square in the decade spanning 2010 to 2020.

People would connect on town squares which were hobby-centric, rather than geography-centric.

Just look at all of us here on Seeking Alpha. 42,000 of you follow us and our work. Most of us are dividend investors. This is how we meddle, virtually.

The reduced need of malls as town squares, and the rise of e-commerce, meant that the writing was on the wall, but many failed to see this.

In 2014, GGP’s CEO Sandeep Mathrani discussed the dual nature of e-commerce, highlighting both challenges and opportunities for mall REITs. He pointed out that while e-commerce was perceived as a significant threat to brick-and-mortar retailers, it could also be integrated into their strategies. Mathrani noted that historical parallels, like catalog sales, had similarly disrupted retail in the past, yet physical stores adapted and thrived.

Note that I’m not extremely well-versed in the intricacies of most of these retail malls, but one of those, I am, Simon Property Group, Inc. (SPG).

SPG is the clear example of the winner, who figured out opportunities and adapted. This took years of investing in its premium properties, spinning off its bad assets into Washington Prime Group (“WPG”), and the share price still has not recovered to its 2016 high of $220.

The pandemic, of course, gave another blow to malls, with the best ones bouncing back since.

I think we’ve covered the story of mall REITs in enough detail though, to learn some solid lessons from the demise of the U.S. mall, which can be applied to Office REITs.

5 lessons from the demise of malls for Office REIT investors

Lesson 1. The combination of technological change and a sudden shock is all it takes to set off a chain of events

The advent of the Internet, and the technologies which we’ve built on this unique means of exchange, have been changing industry after industry.

An economic or financial shock will often highlight distress within the industry. Often it is some form of a recession and federal rate hikes which will bring focus to the problem.

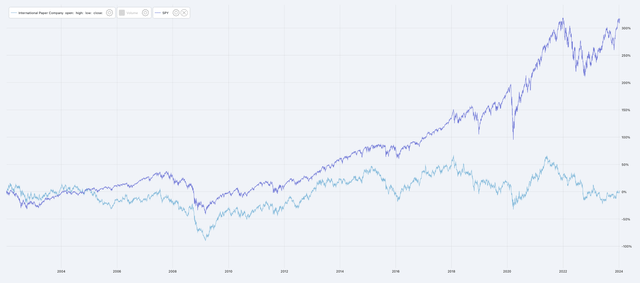

At the turn of the century, the writing was on the wall for the paper industry. International Paper Company (IP) has only matched its 1997 and 2000 highs a couple of times since then. But even if you bought in 2002, after the dust had settled, and you were looking to make a smart investment, excluding dividends, your position would be flat 22 years later. 0% returns.

IP vs SPY (Dividend Freedom Tribe)

Of course, the opportunity cost of being invested in a struggling asset class is just too damn high. And International Paper is the one that thrived in its industry.

Verso Corp, a leading U.S. paper producer filed for bankruptcy in 2016. Van Gelder, a large Dutch paper company, filed for bankruptcy last year in 2023.

Secular changes will grind away, and a financial shock, or a series of financial shocks, will weaken those on the losing side until they have to throw in the towel.

Lesson 2. “Unraveling” is a long time coming

I believe this cannot be stressed enough. Companies can lay off staff. They can increase prices. They can try and tap into new markets. People who have a nice well paid management job want to keep it, and they’ll do what they can to keep the business afloat.

In real estate, we’ve seen with the malls that the unravelling takes a long time because of long-term rental contracts. 10-20 year contracts mean that only 5-10% of leases expire in any given year.

The process of creative destruction isn’t nearly as fast as some might believe.

People were already buying stuff online in 2000, but it wasn’t until 2015-2017 that the unravelling of the U.S. malls happened.

It’s a slow-motion trainwreck.

Now with offices, some Americans have been working from home for years.

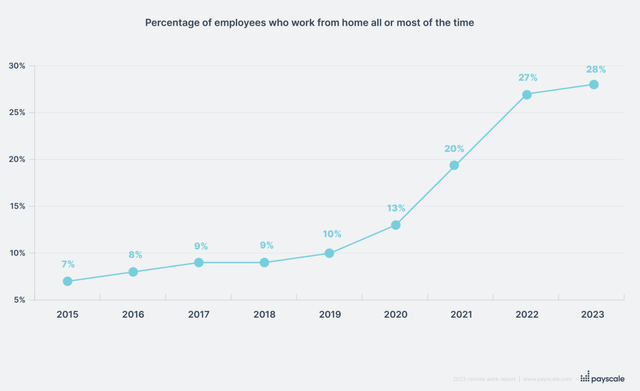

According to a Payscale survey of 400,000 employees, in 2015 7% of respondents worked from home. In 2023, it was 28%.

I’m not saying that this is representative of the whole economy, but what we’re clearly seeing at a wide scale is that there is at most 60% as much demand for offices as pre-Covid, and there has been little progress throughout 2023.

A hybrid model seems to benefit companies and employees.

Those who are talking about the productivity thing I don’t buy it. In fact, I suspect that when you see the likes of Jamie Dimon from JPMorgan Chase & Co. (JPM) expecting employees at the office, it is because he sees the potential disaster and knock-on effects on the economy and, therefore, on his business if nobody went back to the office.

It doesn’t take a lot of math to realize that if you can cut your office space by 30%, you can give up some worker productivity on the days they are not in the office, and that you’ll likely make up for it with a non-monetary induced increase in worker satisfaction.

As vacancies continue to rise with no end in sight, there is little reason to believe that the low retention rates which office REITs witnessed in 2023 will improve in 2024, 2025, or 2026.

There is a lot more pain in sight.

Lesson 3: Nothing is fully priced until it really happens

People who read these articles and say this is “yesterday’s news” and that it is already fully priced, don’t understand how markets work.

As long as more bad news is coming, it’s not priced.

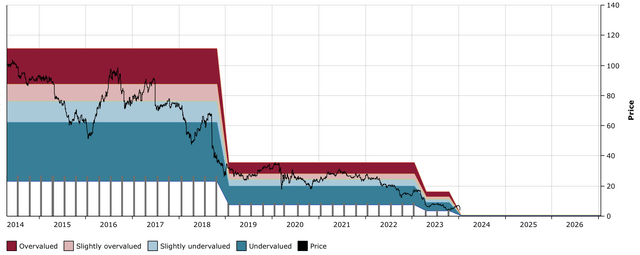

Office Properties Income Trust (OPI) is a good example of this.

OPI DFT Chart (Dividend Freedom Tribe)

You can see that every time the dividend was cut (3x now since 2019), the price took a hit when the news came out.

The writing was on the wall every time, but until something happens, there is always the possibility that it doesn’t happen.

This glimmer of hope, which blindsides long investors who don’t want to give up on their position, means that the market is “pricing” the stock with an overly confident probability of “this won’t happen.”

Then it does happen, and that probability gets removed.

As a rule of thumb in investing, when you say “this is priced in,” it usually isn’t.

Lesson 4: Perma-bulls will always say “BUY”

If you have a SA premium subscription, you’ll be able to see the bullish bias of anyone (me included) that financial authors have.

It is bad business to realize you’re wrong, and because the stock market is tilted upwards, and there are 2 up days for stocks for every down day, and up days are on average up more than down days are down, there is an incentive to keep “blaming the market” on asset price movements.

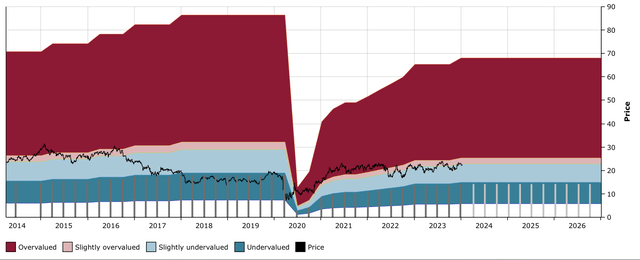

KRG DFT Chart (Dividend Freedom Tribe)

You’ll find articles on Kite Realty Group Trust (KRG), for example, saying it’s a buy from 2015 to 2017. Instead you’ll have had at best a flat 7-9 years.

Taubman Centers was presented as a bull case from 2015 to 2017, at prices ranging from $68 to $55. It got bought by SPG for $43.

Look, we all make mistakes. I’m not taking jabs at any Seeking Alpha author.

We’ve had our fair share of losers. You can look at our article history, you’ll find them.

My point is, that as investors we’re all somewhat subject to the endowment effect, which is to say that we value something higher simply because we own it.

It is not easy, once we’ve written 5 bullish articles, to turn around and say “I was wrong.” When we do, it is often too late, as loss aversion keeps us from gutting the suckers.

I try my best to change my mind when the information available to me changes, but my point here is:

Just because your favorite SA author (me included) says it’s a buy, it doesn’t mean it’s necessarily a buy.

Lesson 5. Even the best quality assets will get hurt in these situations

This one should be quite clear.

The demise of the U.S. mall did not mean the death of the U.S. mall.

There were obviously a lot of closures.

But when possible, assets were repurposed. The business model was changed to an experiential one. Those with the most dry powder, the highest quality assets, and the ability to turn around did so.

Simon Property Group is the largest mall operator in the U.S.

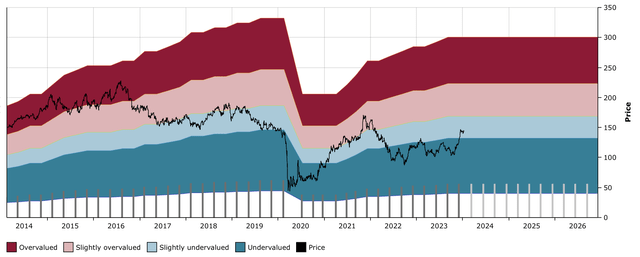

We suggested investors buy SPG in 2021 at $130-135, and have since added shares at $110.

The stock price is now at $143, the pre-pandemic level, and the dividend is rapidly catching up.

SPG DFT Chart (Dividend Freedom Tribe)

It is clear that SPG is still far from recovering its 2014-2016 price levels.

The fundamentals at SPG are great. 95% occupancy, up from 94% in 2022. Rent per sq. ft., is up.

In the same way, I believe that there are superior office REITs: Boston Properties, Inc. (BXP) comes to mind. I’ve owned them in the past.

If we assume that most leases signed before 2019 were your typical 10-year leases, and that they were equally distributed across the decade preceding it, then only half of the pre-pandemic leases have expired. This is back of the napkin calculations.

But as firms are resigning less office space, every time a new lease expires, there is more available supply, which will continue to create downward pressure on ALL offices, not just the lower quality assets.

Superior offices will be able to maintain adequate occupancy (but will likely still take a hit) but will have a tough time charging for it. We’ve seen that premier lease asks per square foot are coming down in recent months.

Conclusions

Investors would be well served in being cautious with these REITs. If you were sitting on big losses, maybe use the recent rally to start cutting your exposure to office REITs.

If you hold on to the highest quality names because of an endowment effect, or because you are afraid to sell “at the bottom,” remember that your funds could be deployed somewhere else that does better than your office REIT names even if you sold at the bottom.

I hope that this article was useful in providing perspective on the unraveling of office REITs.