Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Investors are widely expecting the Bank of Japan to hold off on lifting negative interest rates on Tuesday, but governor Kazuo Ueda is likely to map out more clearly its monetary policy plans following last week’s US Federal Reserve pivot towards easing.

Clear signals on the BoJ’s next proceed or changes in its inflation outlook could provoke major shifts in global financial markets, particularly in light of recent volatility in the yen exchange rate.

With the Japanese economy contracting more sharply than expected and amid uncertainty about the sustainability of rising wages, the BoJ is not expected to change interest rates at its final meeting of 2023.

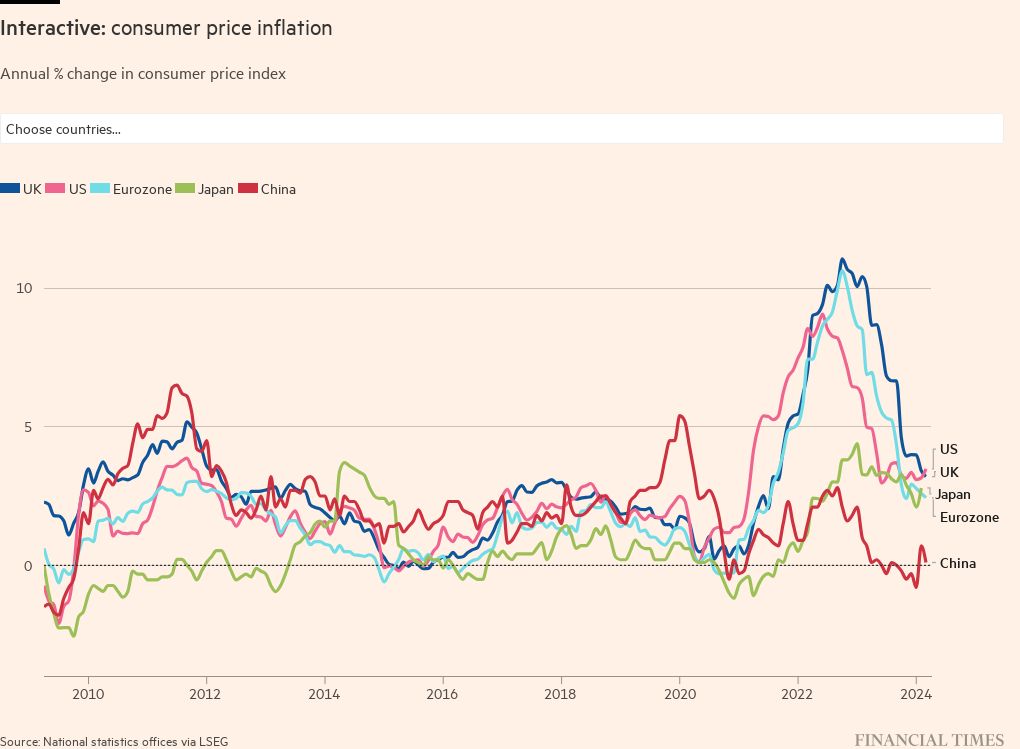

The Fed surprised markets on Wednesday by signalling it would cut interest rates next year, prompting warnings from the European Central Bank and the Bank of England that it was too soon for them to let down their guard against high inflation.

Unlike the Fed, ECB or BoE, the Japanese central bank faces a wholly different challenge of turning what is currently relatively tame inflation into a permanent end to deflation.

Institutional investors in Tokyo said they expected Ueda to preserve negative interest rates on Tuesday. Kazuo Momma, an economist at Mizuho Research & Technologies and a former head of monetary policy at the BoJ, said there was “no reason” for it to “rush to raise rates”.

“From here, I think the BoJ — in the same way as the Fed and the ECB — will proceed with a high degree of transparency so that markets can sufficiently price in the direction of its monetary policy,” Momma said.

He said he expected the BoJ to end negative interest rates in April and make small hikes to short-term rates later in 2024 if it can confirm a continuing trend of rising wages.

Ueda warned earlier this month of an “even more challenging year” ahead for policy management, briefly raising expectations the BoJ would soon scrap its policy of holding interest rates below zero and sending the yen to a then four-month high of ¥141.6 to the dollar.

The yen subsequently fell, but strengthened again after the Fed pivot.

JPMorgan FX strategist Benjamin Shatil said the yen’s rise reflected the difficulties investors were having simultaneously pricing likely moves next year by both the Fed and BoJ.

Previously investors thought Fed cuts would mean the US economy was starting to slow and the BoJ would not raise rates at a time of such economic uncertainty.

“The underlying narrative has been that if the Fed starts cutting, the BoJ cannot really hike. But then you get a situation admire now where there are roughly 30-40 basis points of BoJ hikes and 100-150 basis points of Fed cuts being priced into the market,” Shatil said.

Economists said the BoJ was unlikely to try to surprise markets when it eventually ends its negative interest rate policy. Japan has not raised short-term interest rates since the summer of 2006.

A shock strategy is not necessary since the BoJ effectively scrapped its policy of keeping a hard cap on the yields of 10-year Japanese government bonds when it revised its so-called yield curve control policy in October.

Investors will be watching closely for any hints Ueda might give on Tuesday on the timing of a policy change or any change to his outlook on inflation.

Japan’s core consumer price inflation has been exceeding the BoJ’s 2 per cent target since April 2022, but BoJ officials and economists expect inflation to come down next year.

“We suspect that the BoJ will hint at the upcoming policy revision by including in its statement that it will appraise and confirm the virtuous cycle between wages and prices by the January meeting,” Kentaro Koyama, chief Japan economist at Deutsche Bank, wrote in a report.

Some investors, however, say the BoJ should immediately end a negative interest rate policy that has adverse side effects on markets and financial institutions.

“The first thing the BoJ should do is to abolish excessive monetary policy — its yield curve control and negative interest rates — as soon as possible,” said Naruhisa Nakagawa, founder of hedge fund Caygan Capital.

But Nakagawa said it would be difficult for the BoJ to consecutively raise short-term interest rates in the future. Maintaining 2 per cent inflation would be tough unless Japan saw a pick-up in rents and other services that make up a large part of the country’s consumer prices, he said.