adventtr

No, I’m not drunk or high. And yes, I know who Warren Buffett is.

And I know his investment philosophy. Back around the mid-1990s, I launched regular coverage of Berkshire Hathaway at Value Line. I spoke directly to Buffett himself when I needed updates. And I’m well versed in the literature around Buffett, his own shareholder letters, and other sources.

I’m not going to tell you Berkshire Hathaway presently owns the iShares Semiconductor ETF (NYSEACRA: SOXX) or even any of the stocks in its portfolio. But I can’t tell you he doesn’t. (The publicly traded companies Berkshire discloses are its largest positions. There are many more the company doesn’t disclose.)

I wouldn’t even be surprised if Buffett were to read this and think I’ve lost my mind. That’s OK. I get it. I’ll just respond by suggesting that nobody presented the semiconductor opportunity to him quite the way I’ll now present it to you.

That’s plausible. There was once a time Buffett fans were sure he’d never touch something like Apple (AAPL) with a ten-foot pole. When Apple went public in 1980, Massachusetts banned it as having been too speculative. Yes, really!

But as it turned out Apple was and is legit. And Berkshire Hathaway owns shares.

New times, new information, new opinions . . . we all evolve and do things we once swore we wouldn’t.

So, let’s get to it. Let’s review some core Buffett principals and see how SOXX stacks up.

After that, we’ll see why SOXX is a more Buffett-like choice than the VanEck Semiconductor ETF (SMH).

Buffett As Value Investor, and SOXX

It’s well known that the younger Buffett studied under Benjamin Graham, one of the big celebrities in the Value world. And Buffett made statements the confirmed his respect for value.

But there’s a big difference between for-dummies value and grown-up value.

In the for-dummies world, low ratios (P/E, etc.) are always good. High ratios are always bad.

In the grown-up world, the appropriateness of any price (the valuation ratios for a stock, the prices of cars, houses, vacations, apparel, etc.) is deeply intertwined with and inseparable from the merits of what you buy.

Buffett’s activities reflect. Ditto Seeking Alpha’s quant models.

Berkshire’s largest is Apple. Seeking Alpha’s ratio-driven Valuation grade is F. (The stock needs other, better, factor grades to pull the overall Quant rating up to “Hold.”)

We also see this with two other favorites Buffett praised in his latest February 24, 2024 shareholder letter.

For American Express, Seeking Alpha has a D- grade for Valuation. But strength elsewhere brings the overall Quantitative rating up to “Hold.” Coca-Cola (KO) has a “Strong Buy” Quantitative rating despite a D Valuation grade.

Obviously, I’m not privy to the details of Seeking Alpha’s proprietary formulations. But it’s obvious that their treatment of value is as I described. High valuation ratios won’t scotch an overall investment stance if the stock is sufficiently meritorious.

Merit in the stock market, is based on three things, the required rate of return, future growth expectations, and the level of business risk.

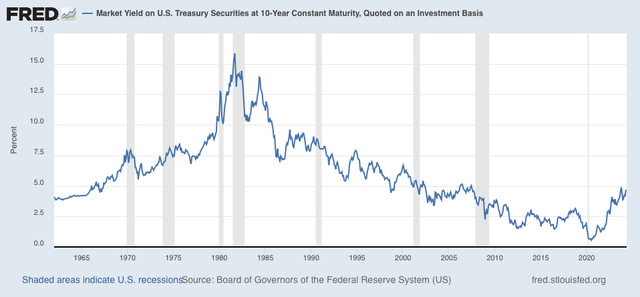

The required rate of return, tied as it is to interest rates, has been a negative recently. But it’s not as if the increases we’ve recently seen kill the case for semiconductors. We can see that by ditching the horse blinders and looking at the big picture.

The artificially low rates we had during the post-2008 financial-crisis period was a godsend to rotten businesses. At last, they could afford capital. So junky companies loved the near-zero post pandemic rates. They were also good for reckless investors.

Rates are now closer to the low end of a normal range. Lenders are back to demanding some measure of competence before throwing money at a company.

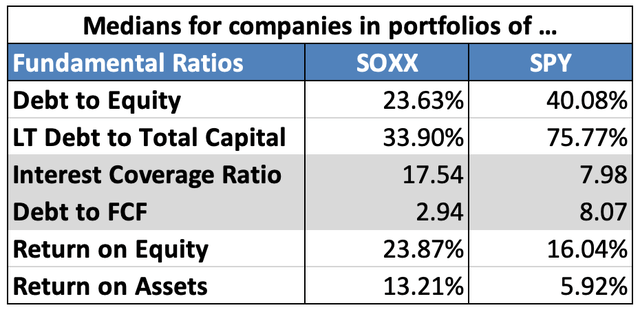

That’s fine for SOXX. Take a look at key median ratios from companies in its portfolio. Notice how they handily beat those in the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY) portfolio.

Author’s computations and summary from data displayed in Seeking Alpha Portfolios

(By the way, I’ve found over many years that medians tend to be more informative than other summary statistics. The more-widely-respected market cap weighted averages can produce amazing distortions if and when big companies experience whacky data items, as most do from time to time.)

Clearly, the SOXX companies’ businesses can handle today’s interest-rate environment.

Rates are also relevant to financial/valuation theory. Stocks are worth the present value of expected future cash flows. For growth companies, we rely more on cash flow from the distant future. Dividing these by higher rates can slash present-day value.

I don’t actually build “discounted cash flow” models because the assumptions they require (such as a growth-rate projection through infinity) are downright crazy. But to quote a line often misattributed to John Maynard Keynes “It is better to be vaguely right than exactly wrong.” (British logician Carveth Read actually said it.)

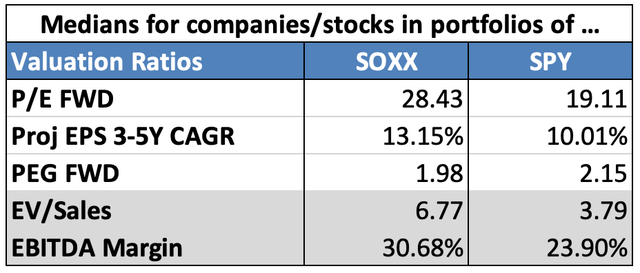

This table suggests some pretty good approximations.

Author’s computations and summary from data displayed in Seeking Alpha Portfolios

The SOXX portfolio is obviously pricier than the SPY. But with SOXX, you’re getting more (in terms of investment merit — growth and quality — for your money.

More growth warrants higher valuation ratios. Better quality (which translates to lesser business risk) also supports higher valuation ratios.

And don’t ignore sales-based valuations. Earnings are sales multiplied by margin. Strictly speaking, that’s net margin. (But for analytic purposes, I prefer EBITDA margin. This omits non-operational and non-recurring items. I also prefer EV/Sales over Price/Sales. Using EV lets permits apples-to-apples comparisons among companies with differing debt ratios.)

Higher EV/Sales ratios are supported by combinations of higher margins, prospects for better future sales growth and prospect for wider future margins.

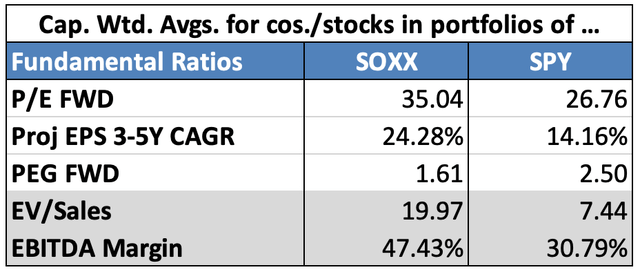

Now, I said above I prefer to look at medians. But the presence of a giant like NVIDIA (NVDA) in the semiconductor word warrants some flexibility. So, here’s the same table using cap weighted averages.

Author’s computations and summary from data displayed in Seeking Alpha Portfolios

As can happen with cap weighting, there are some nutty numbers. But on the whole, we reach the same conclusion. We pay more to own SOXX company shares. But in terms of growth prospects, margin, and quality, we get better “merchandise.

So SOXX fails the for-dummies-value test. But it passes under the grown up, which Buffett has used.

Understandability and SOXX

This is a big thing for Buffett. And rightfully so. In fact, I’m amazed that some folks out there don’t follow such a rule.

I know that because so many people recommend individual bank and biotech stocks. An ETF is one thing. But individual stocks… Seriously! I’ll probably get to this another time.

A few decades ago, I’d have dismissed tech for the same reason… as did Warren Buffett. But to repeat what I said above about new times, new information, new opinions. And, I should, add new levels understandability.

Ordinary life today is more tech centric than ever. So naturally, all who haven’t been hibernating since 1980 better understand tech than they once did.

Suppose I say, “edge computing,” “chip stacking,” or “dynamic memory.” Maybe you know what that means.

But even if you don’t right away, you can pick it up quickly if need be. Just google the phrases. Wikipedia’s explanation can sometimes get wonky. But Google will show you plenty of other sources that better explain.

So, the gap between what the average investor knows and needs to know to invest in tech is a lot narrower than it used to be.

That doesn’t mean we’re all there. Even smart investors can still get migraines from trying to study an individual semiconductor firm’s product line.

But I’m not suggesting any specific company would qualify as a Buffett selection. I’m talking about an ETF that owns 31 stocks.

This level of diversification is critical.

There’s more to diversification than the statistical volatility reduction quants revere. Under normal conditions, stocks in a coherent group will move pretty much together. And quants don’t have the tools to predict noteworthy variations, “outliers.” (Some think they do. Trust me, they don’t.)

But SOXX holders benefit handsomely from reduction in what I’ll call understandability risk.

I couldn’t for the life of me explain why Company A’s chips are better than those produced by rival Company B. Nor could I describe how semiconductor manufacturers (whose shares make up about 20% of the SOXX portfolio) addresses different stages of the process. Nor could I say which ones are best at what they do.

Perhaps I could get by if I at understand relevant business trends for each offering. There’s demand, inventories, looming changes in capacity pricing, etc. But to be honest, I strike out there too.

But, again, we’re looking at an ETF, not an individual company. To do this, we need a top-down view of semiconductors as a whole.

And like Buffett, I’m not an in-and-out trader. I can be patient for stories to play themselves out.

This makes a huge difference.

A company here and there may experience something odd. We see plenty of that every earnings season.

But these things happen with companies in all kinds of portfolios. We presume, usually with success, that portfolio diversification will overpower individual “stuff.”

So now, SOXX becomes very understandable. We do understand the semiconductor big picture.

If electric current is the lifeblood of our technological world, then semiconductors are the cells.

Semiconductors are objects that are halfway between fish and fowl. In other words, they’re halfway between things that conduct electricity (like copper) and things that don’t (insulators we wrap around copper wires). Hence, the “semi” in semiconductor!

I don’t know this because I studied electrical engineering. It’s all over Google!

This same easily accessible source also explains that these objects are put through a “doping” process. That means shoving impurities into them. But there’s a method to this madness. How these impurities are configured determines how electricity moves through them.

These devices have become so important because of all the things manufacturers can do to them.

They can set them up such that the electricity pathways can store a monstrous amount of information (“memory chips”). The pathways can dictate a particular piece of logic (“logic chips”). We can combine these to form microprocessors.

All such gizmos can be sold off for anyone’s use. Or they can be customized for a particular use.

And over time, the industry has been shrinking them. That lets more power flow through smaller areas without generating undue heat.

This is what lets you carry more computer power in your pocket than massive mid-20th century mainframe computers had!

And engineers have more tricks up their sleeves. They can actually stack semiconductors one atop another, connected by material that conducts current up and down the stack.

These now-nano-sized “computer-like things let humans and machines communicate more easily than ever. And it keeps on getting easier. And more recently, it’s become easier for machines to communicate with machines. (Have you ever heard of IoT, Internet of Things? This is it.)

And who today isn’t excited about Artificial Intelligence (AI). Actually, it’s the same old if-then type programming logic we’ve been using since day one, just more so.

AI’s newness comes from new extremes in intricacy. We now do so many if-then paths, that it looks like human thought! To do this, we keep needing, and so far, getting more and more powerful semiconductors… to access more data and process more logic.

So now, I’ll bet you know more about semiconductors than you do about how food processors and restaurants turn fields full of plantings and livestock into meals.

When we switch from individual companies to a portfolio that we can view top down, semiconductors are now quite understandable.

Bear in mind this wasn’t so when Buffett initially shunned technology.

Regular people didn’t have so any devices doing so many things. Nor was Google search available to instantly put so much knowledge at our fingertips. And, of course, we didn’t have sector-specific mutual funds or ETFs.

But in the context of today’s world, semiconductors and SOXX definitely pass the Buffett understandability test.

Semiconductors, SOXX, And Inevitability

This is an important element of Buffett’s philosophy. He favors “inevitables.” These are companies he knows will be around for a very long time. He famously elaborated on this in his 1996 shareholder letter. There, he wrote:

Companies such as Coca-Cola and Gillette might well be labeled “The Inevitables.” Forecasters may differ a bit in their predictions of exactly how much soft drink or shaving-equipment business these companies will be doing in ten or twenty years. Nor is our talk of inevitability meant to play down the vital work that these companies must continue to carry out, in such areas as manufacturing, distribution, packaging and product innovation. In the end, however, no sensible observer – not even these companies’ most vigorous competitors, assuming they are assessing the matter honestly – questions that Coke and Gillette will dominate their fields worldwide for an investment lifetime.

Of course, we do have to temper this with common sense.

Gillette has to work very hard to maintain its position versus, say, Schick and countless private-label offerings.

Coca-Cola must fight tooth and nail for shelf space and customer favor against Pepsi and countless other soft-drink brands, not to mention today’s proliferation of alternative beverages.

But I think we can easily understand the difference between Buffett inevitables and tech. To him, the here-today-gone-tomorrow products, companies, competitive positions made those firms fail the 1996 inevitability test.

It’s a lot different for us when we look, today, at SOXX.

First, and I can’t repeat this often enough, we’re dealing with an ETF, not any individual company.

Nvidia and Taiwan Semiconductor (TSM) are on top of the world today. Will they be ten years from now? Darned it I know. Nor need I care.

If either or both are blown away by new rivals, so be it. SOXX’s mandate is to own the top semiconductor-related stocks (subject to liquidity requirements, etc.). If NVDA or TSM fall out of eligibility, the ETF will no longer own them. If newbies take their places, that’s ok.

This is normal even for supposedly passive ETFs (such as ETFs). The eligible-company roster changes — once per year for SOXX. At the last portfolio, reconstitution, SOXX turned over 18% of its market capitalization.

So, companies need not be inevitable.

Even within a specific company, no individual product need be inevitable. Compare, for example, today’s Gillette product line with what the internet now refers to as Gillette Old Type razors.

Semiconductors, too, can hardly be called a Johnny-come-lately product that may soon vanish. We can debate history. But generally, many date the modern semiconductor from 1947.

That’s when transistor supplanted big bulky vacuum tubes when it came to regulating the flow of electricity. Everything since then has fallen under the heading of improvement. (That’s much like Gillette’s evolution).

Going forward, Gillette offerings will undoubtedly improve. Ditto semiconductors.

The key to inevitability is the product line. And in the case of an ETF, we want inevitability of the industry.

SOXX passes in both respects.

Admittedly, there was once a time when it looked like semiconductors had become a mature cyclical business, like steel.

We had handheld calculators, personal computers, and other early types of electronic devices. But we got intellectually complacent. We fell into the old patent-office trap.

Supposedly, folks back in 1843-44 suggested the patent office should close because all that can be invented has been invented.

Relax… it’s urban legend that sprang from a glowing characterization how of human creativity had been displayed.

But for a while, many semiconductor observers and investors got lazy. They allowed themselves to assume we had reached the outer limits of progress.

We now know that nothing is further from the truth.

We have wearables, GPS mapping, digital health care, instant video streaming, immersive computing/environments, electric vehicles, autonomous driving developments, remote equipment monitoring, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, factory automation, consumer-oriented robot vacuum cleaners, intelligent appliances, etc., etc., etc.

I’m sure there’s much more I failed to list. And that doesn’t even count the new things about which we don’t yet know.

We do know that all this needs more and better semiconductors. This is so whether future semiconductors look like the ones we now use or take on new forms.

Of course the industry still has ups and downs. Inventories and sales always struggle to get in balance. So, semiconductor companies will continue to see strong quarters and bad quarters coming and going.

But Buffett-type investors don’t fret over that.

In fact, Buffett makes fun of those who do. See, e.g., the famous Mr. Market myth. The latter is a fictitious manic-depressive being who over-reacts to everything.

Mr. Market owns semiconductor stocks. And as is to be expected, he overreacts to all normal business fluctuations.

Traders obsess over Mr. Market’s hot and cold machinations. But Buffett-type investors don’t. Instead, we focus on the big picture, what’s real, what’s sustainable, and what’s inevitable.

I say the SOXX passes the inevitability test as well anything we’ve ever associated with Warren Buffett.

SOXX Versus SMH

SMH is actually the largest semiconductor ETF. It has about $18.3 billion in assets. SOXX, with nearly $12.5 billion, is number two.

The third and fourth ranked ETFs in this field are both leveraged. As such, those higher risk offerings are not Buffett-like.

Number five on the list is the SPDR S&P Semiconductor ETF (XSD). Despite the big-time SPDR branding, the ETF itself is much smaller. It has only $1.5 billion in assets.

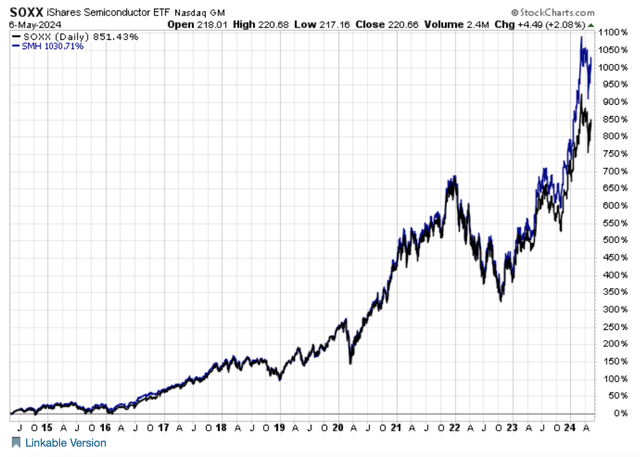

For much of the past ten years, SOXX and SMH performed so similarly, the naked eye can barely see any difference.

But squint at the right, most recent, part of the chart. Notice that SMH opened up a bit of a lead.

That’s not surprising given the two portfolios. Both are modified market weightings. In other words, market cap weighting is the starting point. But the specifics are subject to limits such as to prevent any stock from overpowering the portfolio.

But SMH’s 26 stock portfolio allows bigger weightings than does SOXX’s collection of 35 positions.

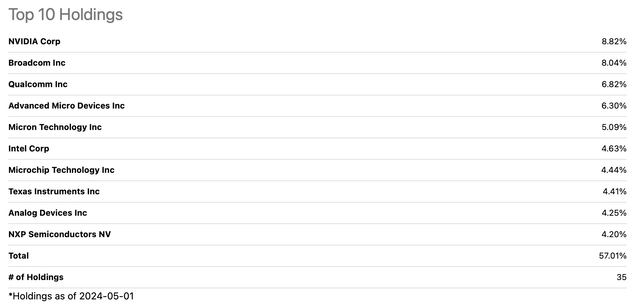

Here is Seeking Alpha’s presentation of SOXX’s top 10.

Not surprisingly, NVDA is number one. Notice, though, it doesn’t overpower the portfolio. The top three positions comprise 23.68% of assets.

That’s a lot. But SOXX never did promise equal weighting.

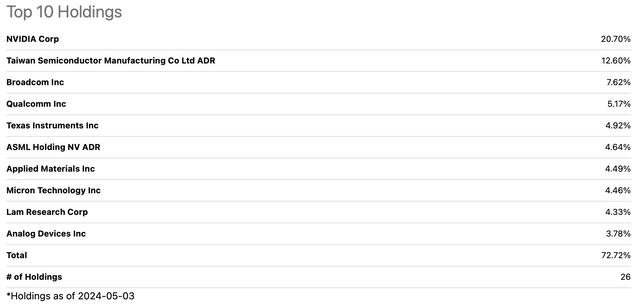

Now, compare SOXX’s top positions to those of SMH.

SMH’s top three hog 40.92% of the portfolio.

That’s a lot. But wait, there’s more.

NVDA is 20.7% of SMH. But it’s only 8.82% of SOXX. That leaves SMH much more vulnerable to the coming and going of hype surrounding this AI bigwig.

But wait, there still more.

SMH’s number two position is Taiwan Semiconductor. SOXX also owns it. But with a 4.8% weighting, it doesn’t even make the SOXX top 10.

Now, TSM is a great and important company. But it’s definitely not a Buffett stock. It used to be. But he sold his stake in 2022.

Despite still loving the business, Buffett expressed concern over tensions between the U.S. and China and the latter’s threats to invade Taiwan. Buffett also noted the U.S. Chips & Sciences Act’s effort to bring more manufacturing stateside.

Generally speaking, SOXX and SMH both own the industry’s main names. But SOXX’s lower stakes in NVDA and TSM make it, by far, more consistent with Buffett’s philosophies. That’s so despite SMH’;s recent near-term outperformance. (Buffett doesn’t chase short-term returns.)

Risks

With a growth area like this, an important risk is that the market may be overestimating the amount of growth we’ll actually see within a plausible (i.e., 3- to 5- year time frame. While growth is inevitable, timing isn’t.

The market may also re-think how much, in today’s dollars, it’s willing to pay for however much growth it thinks will be delivered in a 3- to 5-year time frame. That, and/or an unexpected surge in inflation or interest rates, could compress valuation ratios.

There’s also geopolitical risk. There’s a lot of cross border movement in this business. (And the U.S. Chips and sciences Act aims for a bigger domestic share.) International crises that tighten, or close borders would disrupt the business and push forward the time need for the companies to deliver the growth we expect.

But for now, the biggest and most serious risk is market risk, as I’ll discuss below.

What to do About SOXX

SOXX isn’t just a growth opportunity.

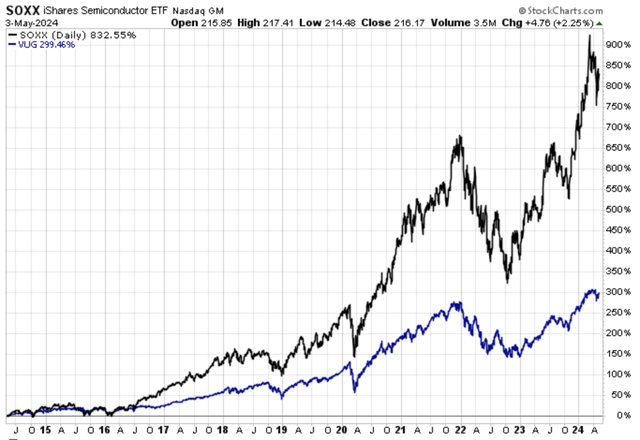

It’s a special kind of growth opportunity. We can see that by comparing five-year price progress for SOXX and the Vanguard Growth Index Fund ETF (VUG).

As you can see both had their ups and downs. And there are periods in which VUG outperformed SOXX.

But the passage of time drowns out little zigs and zags. Over the past five years, SOXX beat the daylights out of the general growth ETF.

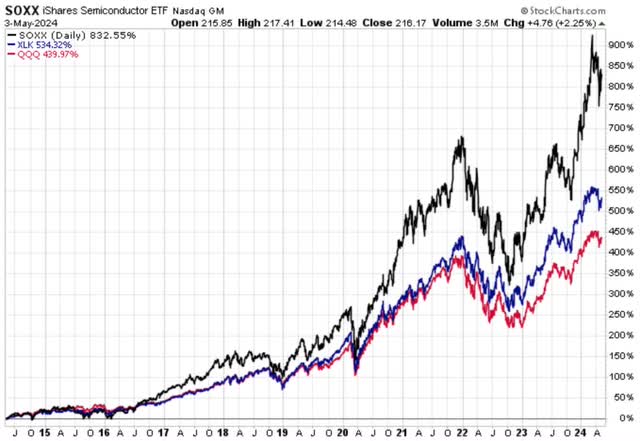

Let’s now zero in on a specific type of growth, tech.

The following chart compares SOXX to two well-established tech benchmarks. One is the Technology Select Sector SPDR Fund ETF (XLK). The other is the popular Invesco QQQ Trust ETF (QQQ). (Note that QQQ isn’t 100% tech. But tech investors revere it and treat it as if it were all tech.

We see that QQQ didn’t blow away XLK or QQQ as it did with VUG. But SOXX did outperform both over the past five years.

So, it’s clear that the market has been recognizing SOXX as a special kind of tech growth. And after the discussion above, we know it’s a reasonably valued, understandable and inevitable growth opportunity.

Even so, and even for the best of stocks and ETFs, the market’s here-and-now enthusiasm waxes and wanes.

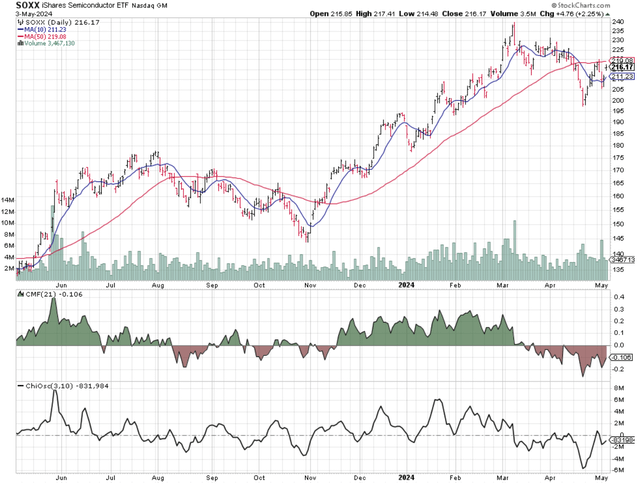

We see here that SOXX’s 10-day exponential moving average (EMA) is below the 50-day EMA. That signifies the absence of upward pressure on the stock.

Now, look at the bottom. Chaikin Money Flow measures institutional trading. The Chaikin Oscillator measures general trading. Both are below neutral. That tells us that while selling and buying are always equal, sellers have more motivation to make the trades right now.

So this far, it’s tempting to be bearish on SOXX. But let’s not jump the gun.

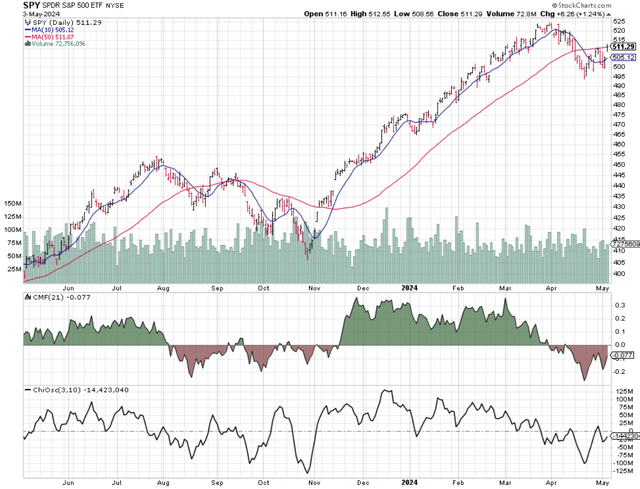

Stocks and ETFs move based on (A) company/group-specific factors and (B) market factors. Don’t underestimate the power of market factors. This is huge. So let’s take a look at the market; the SPDR S&P 500 ETF.

This looks a heck of a lot like the SOXX chart. The 1-day EMA is below the 50-day EMA. Chaikin Money Flow is below neutral. So, too, is the Chaikin Oscillator. If I blur my vision, I’d think I’m seeing the same chart.

So, all the negative things I said about SOXX apply just as much to SPY!

(The charts will signal us if ETF-specific risks mount. We’ll see that as a noteworthy – not matched by SPY –deterioration in the 10-day EMA, the Chaikin Money Flow indicator, or the Chaikin Oscillator.)

Balanced against the market-like risks I see, the Buffett-like bullish considerations give SOXX superior upside potential.

My investment stance depends mainly on whether I think a stock will be better than, in line with, or worse than the market.

Here’s how I apply that to the Seeking Alpha rating system:

- “Strong Buy” means I see the stock as being better than the market, and I’m bullish about the direction of the market.

- “Buy” means I see the stock as being better than the market, but am not confident about the market’s near-term direction.

- “Hold” means I see the stock as moving in line with the market.

- “Sell” means I see the stock as being worse than the market, but am not confident about the market’s near-term direction.

- “Strong Sell” means I see the stock as being worse than the market, and I’m bearish about the direction of the market.

Based on this scale, I’m rating SOXX as a “Buy.”