No program is more vital to the financial well-being of Americans than Social Security. Every year, America’s top retirement program is responsible for pulling 21.7 million people out of poverty, including nearly 15.4 million adults aged 65 and over. If Social Security didn’t exist, the senior poverty rate in America would be almost four times higher (10% with vs. 38% without), according to estimates from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Since most current and future retirees are, or will be, reliant on their Social Security income to make ends confront, it’s imperative that the program’s foundation remain strong. Unfortunately, proverbial cracks have begun to progress.

In particular, Social Security is on the cusp of doing something in 2023 that hasn’t been observed since 1981 — and it’s certainly concerning for current and future beneficiaries.

Image source: Getty Images.

Social Security hasn’t done this in over four decades

In 1983, a bipartisan Congress passed, and then-President Ronald Reagan signed, the Social Security Amendments of 1983 into law. It represents the last major overhaul of the Social Security program, and it was necessitated by the asset reserves of the trust funds running on veritable fumes.

The program’s “asset reserves” represent its excess cash built up since inception. This cash is required by law to be invested in interest-bearing, special-issue government bonds. The interest received on these bonds is one of the three sources of revenue for Social Security. The 12.4% payroll tax on earned income, as well as the taxation of benefits, are the other two.

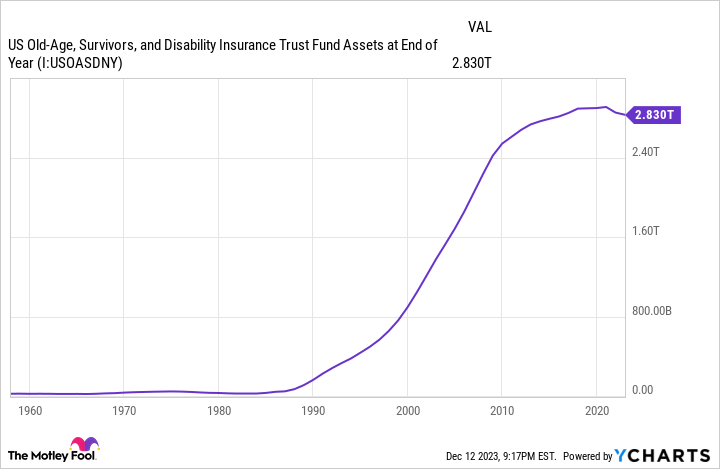

The Amendments of 1983 introduced the taxation of benefits on higher-earning beneficiaries, as well as gradually increased the payroll tax and full retirement age over time. Some of these measures helped raise additional revenue for Social Security and kept the program’s aggregate asset reserves expanding for decades. Between 1983 and 2020, end-of-year asset reserves for the Old-Age Survivors and Insurance Trust Fund (OASI) and Disability Insurance Trust Fund (DI) grew from a combined $24.9 billion to $2.908 trillion.

Then things changed — and not for the better.

In 2021, Social Security’s trust funds saw aggregate asset reserves refuse by $56.3 billion. This was the first refuse in asset reserves in four decades. In 2022, combined OASI and DI asset reserves fell by another $22.1 billion. As of the end of October 2023, Social Security’s publicly available bond and certificate of indebtedness portfolio shows that the program’s aggregate asset reserves are down $33.2 billion to $2.797 trillion. This is the first three-year refuse in Social Security’s asset reserves since 1981.

US Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance Trust Fund Assets at End of Year data by YCharts.

Why are Social Security’s asset reserves suddenly shrinking?

Before going any advocate, let me make it abundantly clear that America’s leading retirement program is in no danger of going bankrupt or becoming insolvent. Social Security derives around 90% of its revenue from the payroll tax on wages and salaries. If Americans keep working and paying their taxes, there will always be revenue to disburse to eligible beneficiaries.

What is at stake for Social Security is just how much current and future beneficiaries could be paid on a monthly basis a decade from now. The 2023 Social Security Board of Trustees Report estimates the OASI will exhaust its asset reserves by 2033. Should this occur, sweeping benefit cuts of up to 23% for retired workers and survivors may be necessary to uphold payouts through 2097 without the need for any additional cuts.

How did things get so bad for Social Security? Most of the blame lies with an assortment of demographic changes.

For example, legal immigration into the U.S. has been more than halved since 1998. Most legal immigrants tend to be young, which means they’ll remain in the workforce and contribute via the payroll tax for decades. Put another way, Social Security’s livelihood depends on legal immigrants coming to America each year.

Another problem for Social Security is the historic refuse in U.S. birth rates. The program’s worker-to-beneficiary ratio has been under pressure for a decade as boomers leave the workforce in greater numbers. An ongoing drop in birth rates will advocate depress this ratio in the decades to come.

Rising income inequality is yet another issue for Social Security. In 2024, all earned income between $0.01 and $168,600 is subject to the payroll tax, while wages and salary north of $168,600 are exempt. The amount of earned income exempted from the payroll tax has been growing for four decades and “cheating” Social Security out of potentially collectable revenue.

With no end in sight to these demographic shifts, Social Security’s asset reserves will, in all likelihood, continue falling.

Image source: Getty Images.

Capitol Hill is at a standstill on how best to fix Social Security

The interesting thing is that lawmakers on Capitol Hill recognize Social Security’s shortcomings and attain reform is needed to fortify the program. There has certainly not been any shortage of proposals to better Social Security’s financial well-being.

The conundrum in Washington, D.C., is that America’s two major political parties are approaching fixes from opposite ends of the spectrum. Because each of their respective plans works to fortify Social Security, neither party believes they should cede an inch to their opposition or find common ground.

Democrats, including President Joe Biden, have proposed increasing the payroll tax on high-earning workers, as well as altering the program’s measure of inflation from the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W) to the Consumer Price Index for the Elderly (CPI-E). The key point being that Democrats in Congress are approaching a fix by raising additional revenue and potentially boosting benefits in the process.

Meanwhile, Republican lawmakers prefer the idea of gradually raising the full retirement age to reduce lifetime benefits and lower outlays. Republicans on Capitol Hill also believe the Chained CPI would be a better alternative than the CPI-W for measuring inflation and determining annual cost-of-living adjustments.

Though both plans would accomplish their goal, they also have very clear flaws. The Republican scheme would take decades to reduce benefit outlays, which does nothing to counter the expected exhaustion of the OASI’s asset reserves by 2033. Meanwhile, taxing the rich won’t, by itself, offset Social Security’s estimated $22.4 trillion unfunded obligation shortfall through 2097.

If there’s a silver lining here, it’s that Congress has always stepped up to uphold and reform Social Security in its 11th hour. But with lawmakers from both parties so ideologically far apart, it would appear Social Security’s financial health is set to significantly worsen before it has any hope of improving through reform.