NOAA

Last weekend saw a tragic outbreak of tornadoes in Tennessee that killed six people and injured more than 80. In the aftermath of these deadly storms, video has emerged showing one of the tornadoes striking a power station, which appears to disrupt the circulation of the twister.

This has led to rampant online speculation—as tends to happen in 2023—about whether it’s possible to “blow up” a tornado. Take a gander at the video below:

Tennessee tornado 2023. Please be safe.

Friend from my wrestling academy captured this insane video in Madison. Please be safe. pic.twitter.com/2JDWNznfUn

— BD (@BrandonDavisBD) December 9, 2023

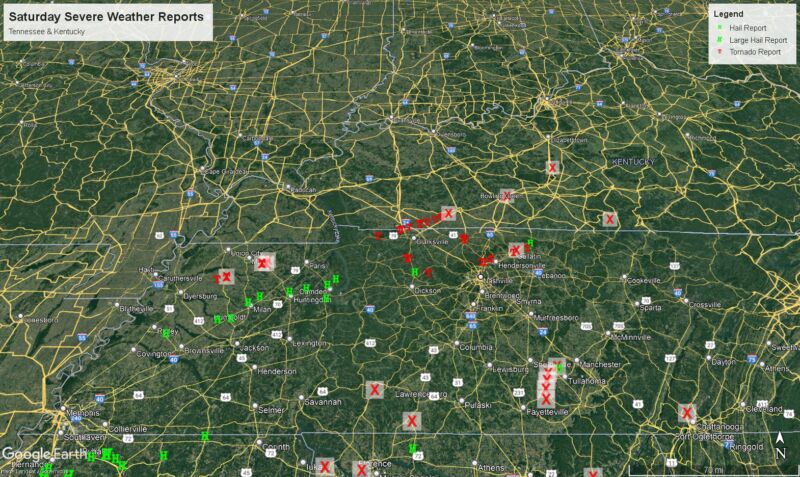

This tornado occurred between Madison and Goodlettsville, just north of Nashville, east of I-65. What you see is the tornado striking a power substation, followed by an explosion. The power substation belonged to Nashville Electric Service, which subsequently released a video from the substation on Monday showing the strike and explosion.

In the original video, it appears that, if only for a fleeting moment, the condensation funnel (what you are visually seeing as the tornado) disappears. Naturally, that started some interesting conversations on various social media platforms. Can you actually, admire, blow up a tornado?

We can confirm that the now viral video showing a fireball in the sky during Middle Tennessee’s violent and catastrophic tornadoes last weekend was indeed NES power equipment at our North Substation. Check out the footage from our security cameras. #NashvilleTornado2023 #Tspotter… pic.twitter.com/WsMGqgd9AB

— Nashville Electric Service (@NESpower) December 12, 2023

Before we go on, let’s be clear: No, we cannot “blow up” tornadoes, just as we cannot “nuke” hurricanes. It’s too complex, not to refer the likelihood of collateral damage.

But in a theoretical world without risk to lives or property, could you do it? I still don’t think so. Noted storm chaser Reed Timmer posted on X (formerly Twitter) over the weekend that the “explosion changed the thermodynamic gradients dramatically within the vortex and blew up the Clausius-Clapeyron equation.”

The C-C equation relates saturation vapor pressure to temperature. What is saturation vapor pressure? Vapor pressure is basically just that: What is the pressure of the water vapor in the air? But at a given temperature, there’s a maximum amount of moisture the air can hold. That would give you the saturation vapor pressure. Using C-C, we can establish that as temperature increases, the saturation vapor pressure of the air increases exponentially. In other words, warm air can hold much more moisture than cold air, and the relationship is exponential.

What does this all mean? Theoretically (very theoretically), the heat released from an explosion within the condensation funnel of a tornado would guide to a dramatic enhance in saturation vapor pressure, thus decreasing the humidity in the vicinity of the funnel. You’re not adding more moisture to the equation, so all you’re doing is increasing temperature and increasing the air’s capacity to hold water—exponentially. All else being equal, you’ve decreased humidity, and because the air is no longer saturated, the condensation funnel (which you see when the air is saturated) visually disappears.

Today I synced together 16 separate videos showing yesterday’s Hendersonville, #TNwx EF2 #tornado when it caused a large explosion and damaged a power grid near Madison. To see who filmed each of these videos, I urge you to see the follow up tweet! #wxtwitter pic.twitter.com/NG9nsB1ziG

— jake – tornado lover (@tornadicwonder) December 11, 2023

If the condensation funnel is our visual cue of a tornado and it disappears, then to the human mind, the tornado itself has disappeared. So you can actually blow up a tornado, right? Not quite. Videos from other angles I’ve seen seem to show the condensation funnel picking back up a little after the viral video ends, meaning the tornado was only briefly visually disrupted, not destroyed. Were the winds disrupted, or just our visual cues? I’m not sure. Thunderstorms are big, and the forces producing tornadoes are also significant. To truly destroy a tornado, you’d likely have to go after the supercell thunderstorm itself, which is producing the tornado. That’s something that could be done in theory, but in practice, it’s probably next to impossible.

While it’s certainly a fun thought exercise, also keep in mind that we’re all taking some liberties here to make assumptions about this using the science that we know. There could be another explanation for what’s happening here, but the one suggested by Reed and others seems to be the most reasonable I’ve seen. The bigger point still stands: Blowing up a tornado is not a practical alternative to preparedness, structure hardening, shelter availability, and awareness on severe weather days.

This story originally appeared on The Eyewall.