DNY59

The post-COVID inflationary surge was transitory after all.

In this article, I’ll explain why.

The story is pretty simple, really. Federal Reserve Chairman Powell’s instincts of calling inflation “transitory” were correct. He was just looking at lagged data in 2021 and 2022 that failed to show the real-time spike in consumer prices, and now he exudes excess caution because he’s looking at old data that still shows the inflation we were experiencing a year or more ago.

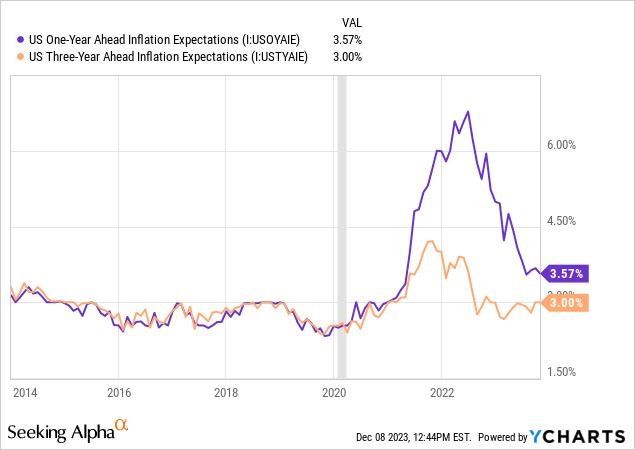

Both investors and consumers seem to see through Powell’s relative hawkishness.

The proof that investors see through it is in the rapid refuse in long-term interest rates since the beginning of November. The proof that consumers see through it is in the steep drop in inflation expectations.

The “higher for longer” narrative that the Fed popularized earlier this year is now being rejected by the market and consumers alike.

Over the last few years, more and more inflationistas have come out of the woodwork making the argument that the world is now in a new secular inflation environment, similar to some degree to the Great Inflation era from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s. Labor shortages, deglobalization, decarbonization, underinvestment in fossil fuels, and excessive government spending are typically the reasons given to uphold the secular inflation thesis.

I think this secular inflation thesis is severely misguided.

In fact, I’m of the view that the global economy and US economy specifically are simply returning to their previous state of low growth and low inflation now that the idiosyncratic events surrounding COVID-19 are fading. All else being equal, things will stay that way indefinitely.

The reason I believe this is that what I call the “Five Horsemen of Deflation” are returning to the scene and reasserting themselves.

These Five Horsemen are:

- Demographics: Aging populations and falling birth rates put downward pressure on economic, labor force, and consumer price growth.

- Technology: Productivity-enhancing technological advancements are inherently labor-saving and deflationary.

- Over-Indebtedness: Debt levels above certain thresholds have been demonstrated by numerous academic studies to weigh down economic growth and suppress inflation.

- Globalization: International trade puts downward pressure on net importer nations’ inflation and wage growth.

- Inequality: A smaller portion of money in the pockets of those with a higher propensity to spend translates into lower-than-otherwise aggregate demand.

These five forces are coming together to furnish a mighty disinflationary trend (read: falling rate of price growth), just as they did in the 2010s.

I call them the “Five Horsemen of Deflation” because they bring about prices to be lower than they otherwise would be. On their own, they would bring about deflation, but there are always other forces at play in the economy.

Of course, I should caveat that my argument is not that there won’t be any inflation anywhere going forward. Going forward, there will likely be pockets of higher inflation in the economy, such as commodities related to green technology (e.g. lithium, copper, etc.) and healthcare. But these pockets should remain isolated and exert little upward pressure on overall consumer prices.

In what follows, I’ll cover the Five Horsemen of Deflation argument while also responding to the arguments of the secular inflation camp, and then I’ll infer with some brief thoughts on investment implications.

The Kryptonite of Deflation: More Money

The Five Horsemen are persistently working in the background and tend not to capture much attention. All else being equal, they will effectively exert downward pressure on prices.

But, of course, it’s possible that inflationary events pop up that supersede the Five Horsemen. Wars between major world powers, pandemics, widespread droughts and other natural disasters… these can all trigger bouts of inflation, either by disrupting supply or spurring governments to take measures that enhance the money supply, or both.

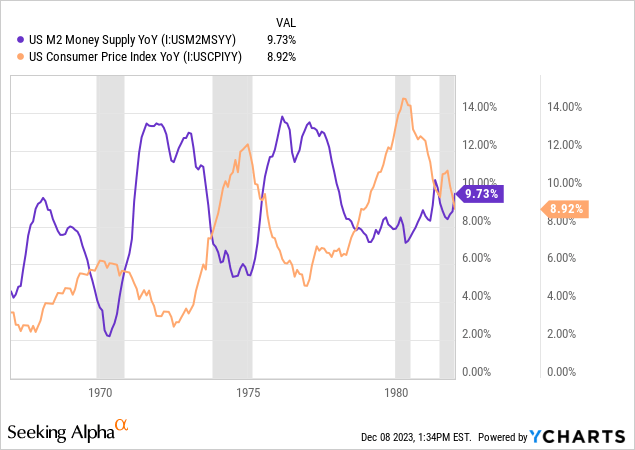

COVID-19 was one of these inflationary events. It caused both a severe disruption in supply and an absolutely huge fiscal stimulus-fueled growth in the money supply. Within a year, this deadly combination resulted in a surge in consumer prices.

But the fiscal stimulus did end. So did the supply shortages.

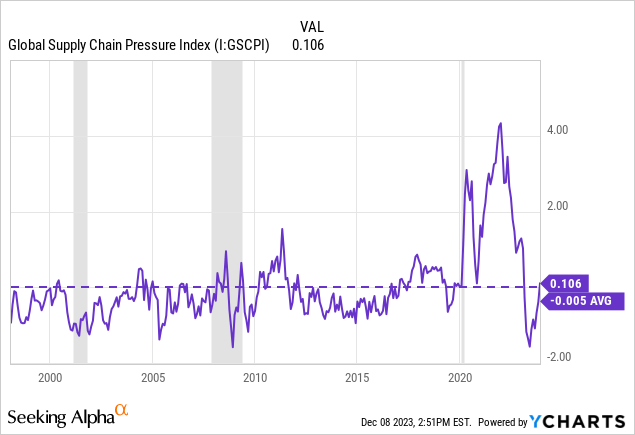

And then, of course, there was the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 that also caused a major disruption in global supply chains, especially for Ukrainian wheat and Russian oil & gas.

You can see the impact of the war in the spike in global food inflation in the Spring of 2022.

However, notice that since then, global food prices have receded as the Ukrainians found other ways to export their wheat. Likewise, the global supply of oil and gas rebounded as the Russians found other ways of bypassing sanctions to export their fuels.

Thus, as the sources of the inflationary bulge receded, so also now is inflation receding.

Some fear that this pullback in inflation is only a head fake, the calm before the next inflationary storm begins. These inflationistas point to the 1970s, when inflation slid for a while only to make a higher resurgence, then cooled again only to make yet another even higher resurgence.

It’s possible this could happen, but it would have to have a bring about.

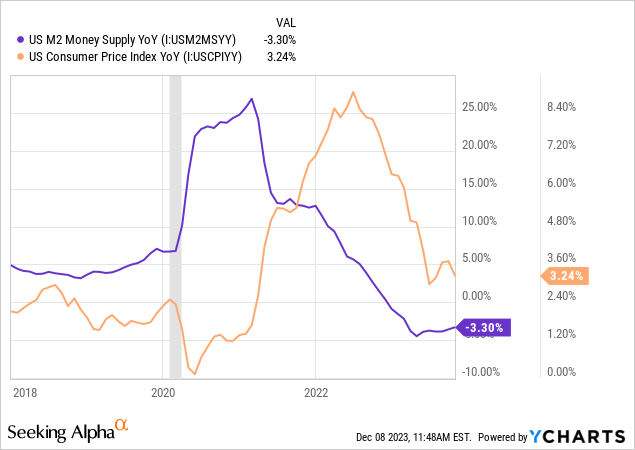

From the mid-1960s to the early 1980s, the bring about for each big spike in inflation was a preceding surge in the money supply.

Yes, there were other factors at play during the Great Inflation period: the Vietnam War, the burgeoning of Great Society welfare programs, the oil embargo, Baby Boomers reaching their prime consumption years, high unionization of the labor force, and so on.

These factors almost certainly increased structural inflation to some degree. But it was the huge spikes in the money supply that caused the subsequent spikes in inflation.

Say’s Law

The fundamental point about the money supply comes down to Say’s Law. This principle, first articulated by the 18th century French economist Jean-Baptiste Say, can be expressed in a confusing way and a not-confusing way. The confusing way is that “supply creates its own demand.”

The not-confusing way to explain Say’s Law is that it is economically healthy for income to be tied to production. Workers produce, thereby increasing supply and simultaneously earning an income with which to consume. In this way, there is a virtuous relationship between supply and demand.

Say’s Law is violated when income becomes divorced from production, especially when incomes grow artificially in some way while production does not.

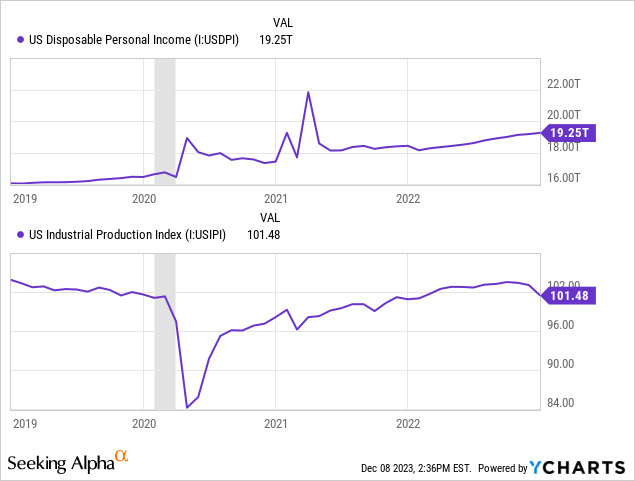

COVID-19 was a textbook case of this. Uncle Sam sent out trillions of dollars in “economic impact payments” (stimmy checks), paid employers not to lay off unproductive (through no fault of their own) employees, and massively beefed up unemployment benefits.

Hence we found that exactly as employment and production plummeted, disposable personal income spiked.

In a governmentally unmedicated recession, falling employment leads to both lower production and lower incomes, which in turn leads to lower demand.

Not so in the COVID-19 recession! The money supply (and consumers’ spendable income) surged from Uncle Sam’s unprecedented level of fiscal stimulus even while production and supply chains collapsed.

This caused a huge but one-time wave of inflation across the economy, both domestically and globally.

Eventually, the stimulus fully worked its way through the system while employment and production rebounded and supply chains smoothed out.

The economy, admire the human body, has a remarkable way of healing itself when the source of harm is removed.

I repeat: The primary source of inflation is and has always been rapid growth in the money supply, especially (almost exclusively) when that growth in the money supply is divorced from production.

Therefore, if you’re concerned about inflation making a resurgence, watch the money supply.

The Deflationary Impact of Aging Demographics

Aging demographics is often cited as an inflationary force because more older workers retiring than younger workers entering the workforce could guide to a sustained labor shortage, which could in turn guide to wage growth and rising consumer prices as businesses pass on the higher labor costs to customers.

This logic may be valid in a vacuum, but in the real world, it doesn’t hold up.

As we’ll cover in the next section below, productivity-enhancing technologies allow businesses to do more with less — that is, produce more with fewer workers. As the labor force plateaus or shrinks, businesses invest more in labor-saving technologies to preserve output as their older workers retire.

The COVID-19 labor shortage was a unique case, because not only did a big wave of Boomers retire all at once, there were also many younger workers staying out of the workforce for a variety of reasons. The recent surge in wages, then, was idiosyncratic. It is not necessarily the beginning of a new, demographics-driven enhance in wage growth.

The deflationary aspect of aging demographics concerns the demand side. Older people and especially retirees simply spend less money than younger age groups. This is a well-documented and long-running phenomenon.

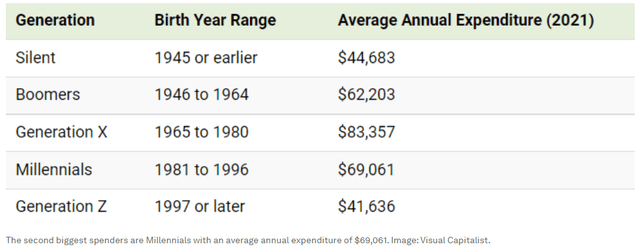

Here’s data on consumer spending by age group from 2021:

Consumption by age forms a bell curve, peaking in mid-life around age 45-55. This is the period of life when workers typically reach success in their careers, families buy bigger houses and nicer cars, kids are in middle and high school, and vacations are becoming more extravagant.

Spending declines a bit from age 55-64 as parents become empty-nesters, then spending drops off a lot around the mid-60s, typically coinciding with retirement.

Although it is true that Boomers retiring will reduce the labor force, it will also reduce aggregate consumer demand as they age.

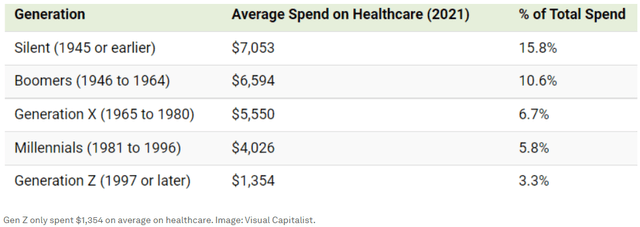

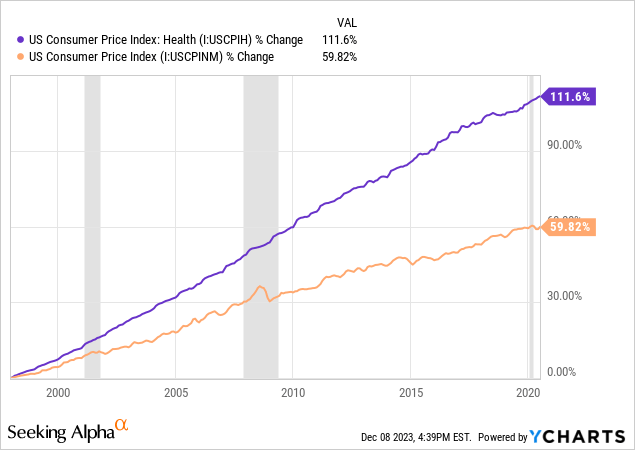

This age-related consumption bell curve is true of almost all categories of consumer spending, except one: healthcare.

Unsurprisingly, the older one gets, the more they spend on healthcare.

This is the fundamental reason why I foresee healthcare inflation continuing to be elevated in the future. This is one of those pockets of inflation that will probably persist above the CPI average going forward.

Until the post-pandemic inflationary surge, healthcare inflation had a long history of outpacing overall inflation.

Now that the post-pandemic inflation is fading, I believe that trend will resume.

Aging demographics is inflationary only for the healthcare space. Everywhere else it is a deflationary force.

Keep in mind that due to the falling birth rate in both the US and around the world, this deflationary pressure from aging demographics is not a temporary phenomenon.

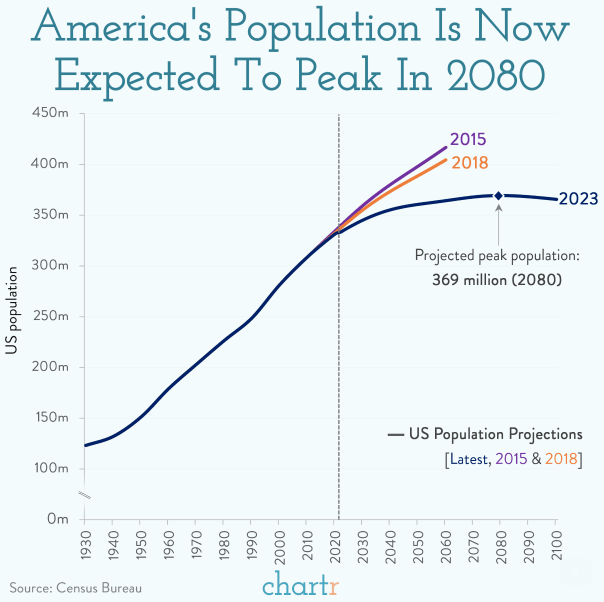

The current population of the US is around 340 million, and the latest Census Bureau projection estimates that the nation’s population will peak around 2080 at 369 million people. That population level is about 8.5% higher than today’s and implies a mere 0.15% average annual population growth.

Chartr

Unless the birth rate makes a recovery or immigration significantly increases, it appears as though the US (and most of the world) will never have a demographically driven uptrend in consumer demand again.

As each generation gets smaller, aggregate demand growth will likewise shrink. Someday, perhaps, the growth in consumer spending will cease entirely, and aggregate demand will refuse.

Although it wouldn’t be surprising to see fiscal and monetary policymakers step in to hinder such a refuse if and when that day comes.

Technology Enhances Productivity And Reduces Labor Demand

As mentioned above, we have to keep in mind that technological advancement reduces overall demand for labor while also opening new avenues for new and other types of jobs.

Hundreds of years ago, over 90% of the population worked in agriculture. Now that percentage is 1-2% in developed economies. The tractor eliminated millions of jobs over the course of several generations, saving billions of man hours and dramatically increasing labor productivity.

Much the same story could be told about the printing press, the steam engine, the automobile, the airplane, the computer, the smartphone, and so on. They eliminated countless jobs by significantly increasing productivity, not immediately but typically over the course of a generation or so.

The Internet did the same thing. The Dot Com bubble was a relatively brief event in the stock market, but the Internet’s gradually impacting and shaping the economy has played out over 20-30 years and is still ongoing today.

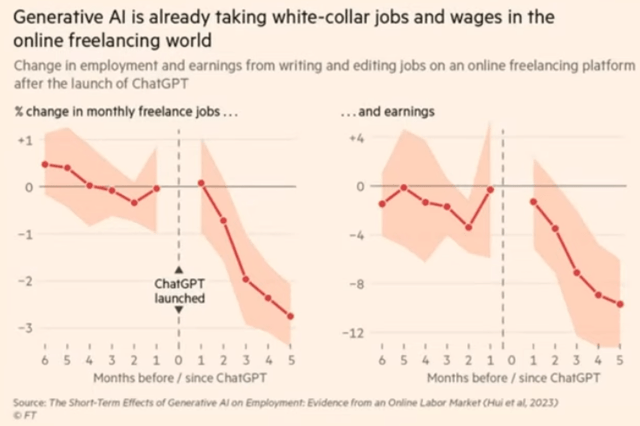

The same will be true of artificial intelligence. We are in the midst of the initial hype cycle for AI right now, but it will probably take decades before the bulk of its potential impact will be felt.

Already, we are seeing an impact on certain white collar jobs such as freelance writing and editing. Both job postings and pay for these roles has plummeted since the introduction of ChatGPT.

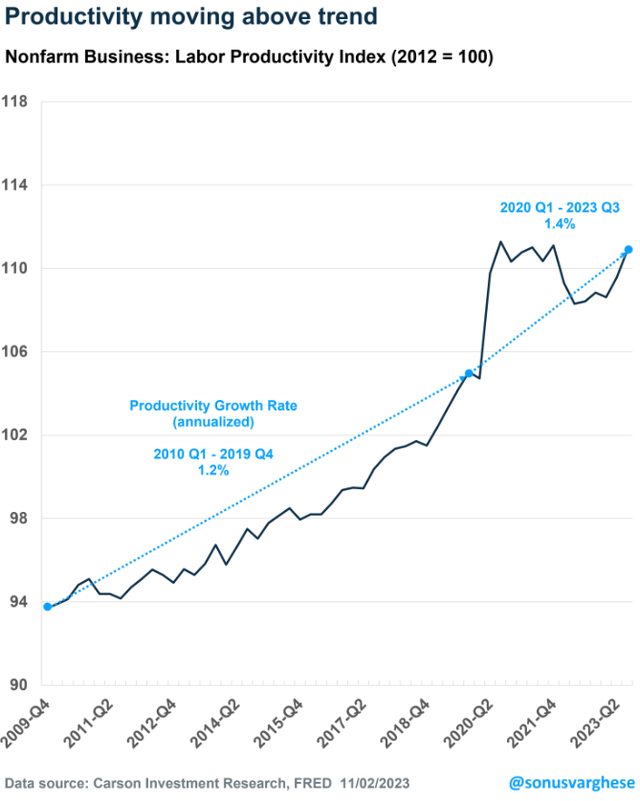

Moreover, there is some evidence of the above argument that as the labor pool shrinks, employers invest more in labor-saving technologies.

Consider the fact that labor productivity has ticked up to an average annualized rate of 1.4% since the onset of COVID-19, compared to 1.2% during the 2010s when labor was relatively cheap and abundant.

Businesses always look to lower their costs, and for some businesses, labor is one of the largest costs. As with so many other areas of the economy, the cure for high prices is high prices, because it spurs businesses to seek out alternatives to continuously increasing wages.

There is ample evidence that, after the shock of a wave of Boomers retiring and younger workers sitting out of the workforce during the pandemic, the labor market has normalized.

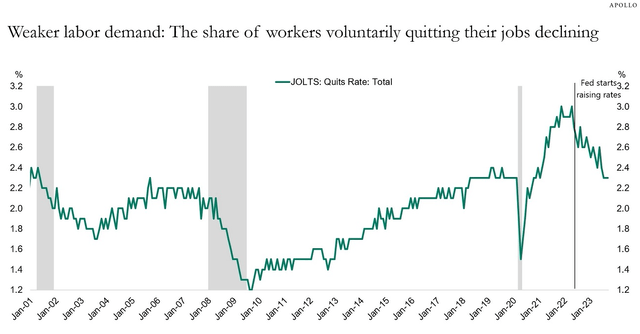

For example, the quits rate (a signal of employee confidence in getting another, better job elsewhere) has dropped back to its pre-pandemic level.

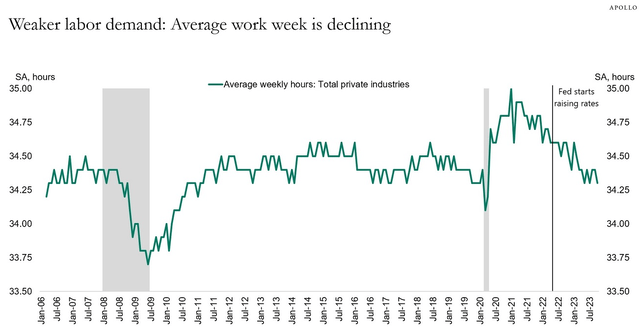

Likewise, the average number of hours worked per week has dropped down to the low end of the 2010s range.

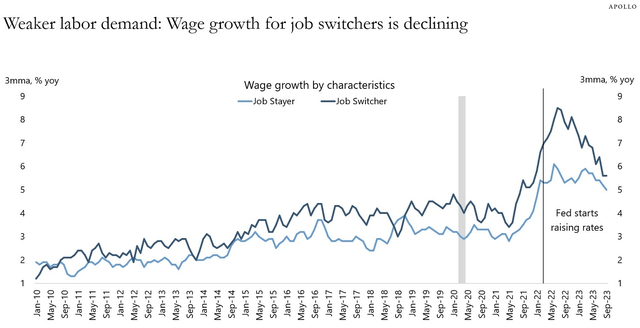

What’s more, the extraordinary wage growth achieved by job switchers in the post-COVID years has cooled dramatically (going a long way in explaining the drop in the quits rate), falling right alongside wage growth for the job stayers.

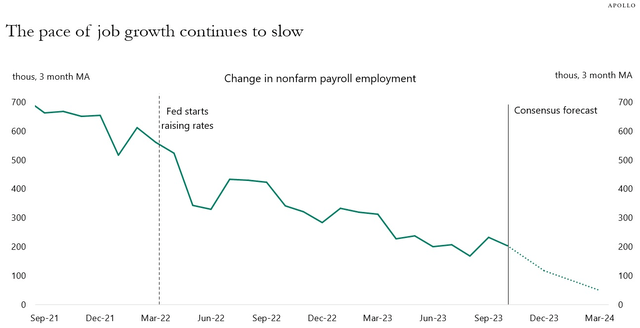

And finally, we should witness the trend of monthly job growth has been very clearly downward over the past two years and appears set to turn negative sometime in Spring 2024.

In short, then, the dynamics playing out in the labor market appear to uphold the “one-time, idiosyncratic event” thesis I have been espousing instead of the “permanent labor shortage and high wage growth” thesis.

Supporting this argument is the fact that there has never been more labor-saving technology available to employers than we have today. And American tech companies are hard at work inventing the next generation of labor-saving technologies as you read this.

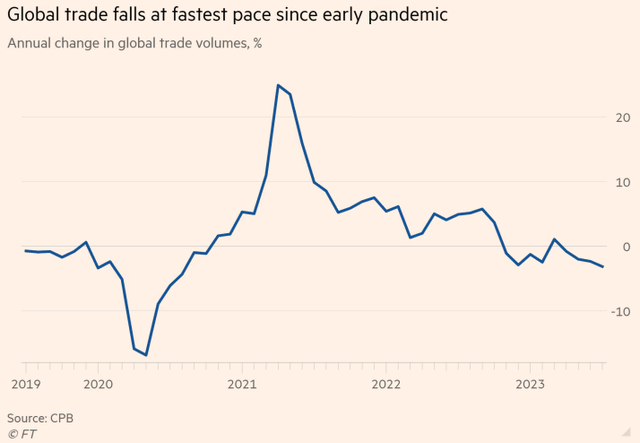

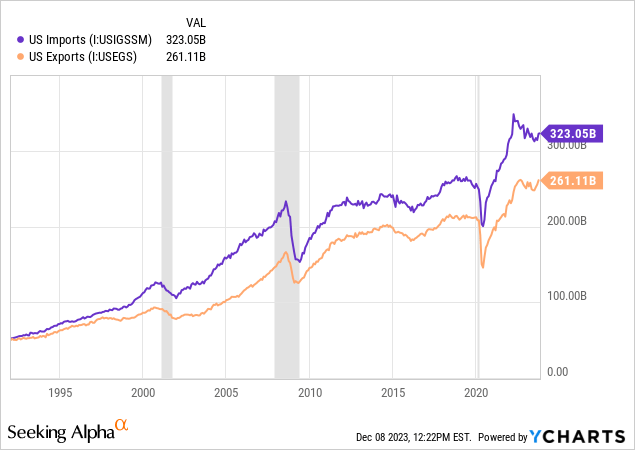

The Death of Globalization Has Been Greatly Exaggerated

Generally speaking, globalization is a deflationary force, and deglobalization is an inflationary force.

But though “deglobalization” has won the narrative war, globalization continues to quietly plug away behind the scenes.

Global trade volume reached a record high of about $32 trillion in 2022, according to the UN Conference On Trade And Development (UNCTAD).

It has pulled back somewhat in 2023, but that is largely because of a shift in consumer spending from goods to services this year, not because globalization is dying.

If you look only at the US, there’s a clear long-term trend.

Volume of imported goods into the US is down a bit from its peak in 2022, but not by that much. Again, this was mostly a function of a shift from consumer spending on goods to services. Meanwhile, volume of US exports are hitting all-time highs.

Could someone point out in this chart when deglobalization began?

Various political measures are being taken to curtail international trade and spur onshoring, to be sure. The Trump administration began to reverse the long uptrend in imports from China, and the Biden administration has heavily incentivized the reshoring of certain strategic industries admire semiconductors and renewable energy supplies.

But the utility of offshoring most types of manufacturing remains quite high. That’s why US businesses continue to do it.

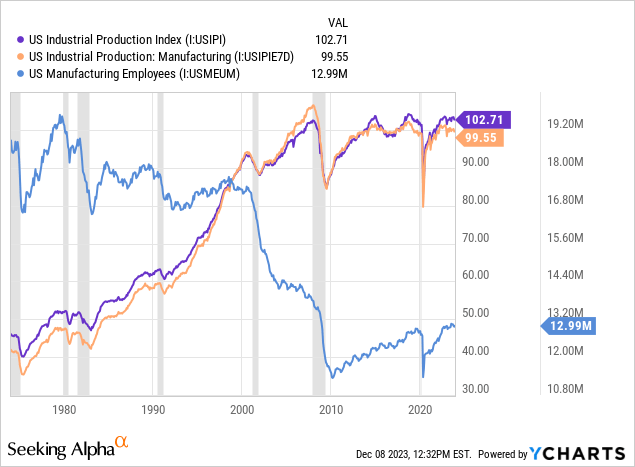

Again, in the chart below, could anyone point to the moment that deglobalization began?

Neither US industrial production broadly nor manufacturing specifically have made a new high since 2007. During the Great Recession, many producers shuttered their factories in the US, and when they reopened, they did so in other countries with lower labor costs.

US manufacturing employment has been rising, but it is following the same trend that was in place during the 2010s.

There are, of course, many well-publicized stories of American companies building factories on US soil again. But most of these are cases where the government is heavily incentivizing it with subsidies.

As many think pieces with almost identical headlines (such as this one) have attested in the last few years, “globalization isn’t dead, it’s just changing.”

Switching from a supplier in China to one in India, Indonesia, or Mexico isn’t deglobalization. To the degree international trade is evolving, this is the primary way it’s happening.

Final Rebuttals To The Secular Inflationistas

What about the last two Horsemen — Over-Indebtedness and Inequality?

I’ve covered these in thorough detail in my “Monetary Death Spiral” articles from 2019 and 2020:

Although I didn’t foresee the degree to which inflation would take off back in 2019 and 2020, I do think we’ll be back into Monetary Death Spiral mode within a year or two.

Underinvestment In Oil & Gas

What about the argument that underinvestment and under-production in the oil & gas space will bring about energy costs to persistently rise, fueling secular inflation?

That argument isn’t pushed much these days, perhaps because the price of oil has slid all the way back to about $70/barrel and gas is far closer to its multi-decade lows than its highs.

Standard & Poor’s recently released a investigate that found big oil companies have “virtually no extra borrowing costs” compared to other issuers with the same credit ratings in other industries. Plus, many upstream oil producers’ stock prices remain near their all-time highs.

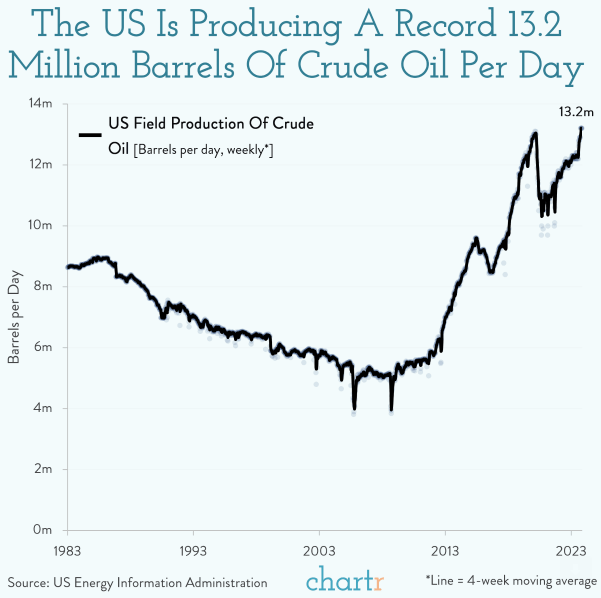

Moreover, the US energy sector recently reached record oil production, and these US producers account for 80% of global oil supply expansion this year.

Chartr

Meanwhile, OPEC has been cutting production levels recently, which makes clear that there is even more production capacity available than what is being used.

So it is difficult to see exactly how the institutional underinvestment in energy companies has hindered production or will bring about a sustained uptrend in oil & gas prices going forward.

Deficit Spending

This is a tough one, because some research does show that high fiscal deficits can guide to increased inflation. But it all depends on what the money is being spent on.

For example, increased defense spending does tend to advocate higher inflation in military goods, but this has little to no effect on consumer inflation. When was the last time you bumped into someone who said, “I went to the store to buy a cruise missile the other day, and you wouldn’t believe the prices of those things!”

What about federal government interest payments? Do those bring about inflation? Given that most federal debt is owned by government pension funds (e.g. Social Security), institutions, and foreign investors, higher government interest expense almost certainly does not enhance inflation.

Entitlement spending on programs admire Social Security and Medicare have increased quite a bit and are projected to grow far more in the coming decades. But these forms of government spending grow based on the eligible recipient population and cost of living adjustments (“COLAs”). Thus, these programs’ expenses enhance after inflation has already taken effect.

The COVID-era fiscal stimulus measures were designed to streamline consumer spending. But normal government spending, deficit-financed or not, does not tend to have a measurable effect on inflation. A 2016 investigate from the St. Louis Federal Reserve found that, paradoxically, a 10% enhance in government spending correlated with a 0.08% decrease in inflation.

Investment Implications

Other than a few isolated pockets admire renewable energy commodities and healthcare, the world appears to be returning to a state of low growth and low inflation. The Five Horsemen of Deflation have galloped back onto the scene. Their absence over the last few years was, shall we say, transitory.

I don’t necessarily think developed economies will enter prolonged periods of actual deflation, because growth in the money supply should offset the working of the Five Horsemen going forward.

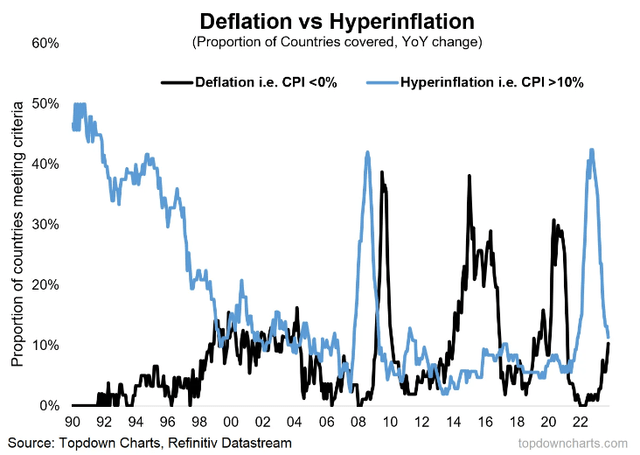

But a great many countries will see deflation. A rising number of them already are seeing deflation, while a plummeting number of countries are suffering from >10% inflation.

To be successful investors, we’ve got to skate to where the puck is going, not where it’s been or even where it is now.

My favorite type of investment is net lease real estate investment trusts (“REITs”). These companies own single-tenant properties with long lease terms and contractually fixed rent rates, often including fixed annual rent escalations. They’re admire bond alternatives, only better than bonds because of property valuation upside and rent escalations.

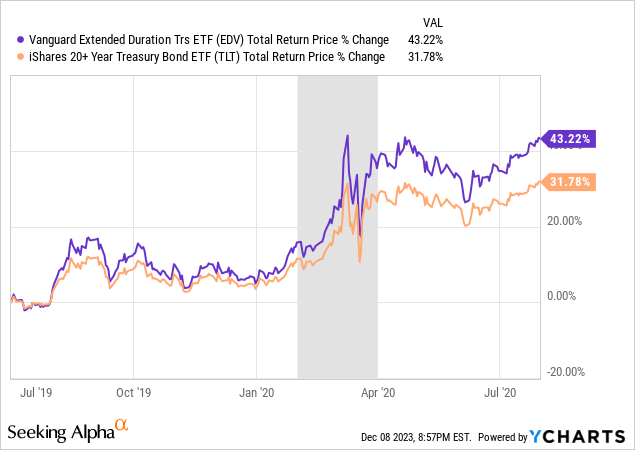

Long-term bonds such as those in the Vanguard Extended Duration ETF (EDV) and iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT) do very well in recessions and periods of low and falling inflation. See, for example, how well they did during the initial stages of COVID-19:

But these work best, in my opinion, as trading vehicles.

As a long-term investment, I prefer to own a company with bond-admire qualities that can survive during short-term periods of rising inflation and thrive during periods of falling and low inflation.

Net lease REITs (NETL) generally do exactly that.

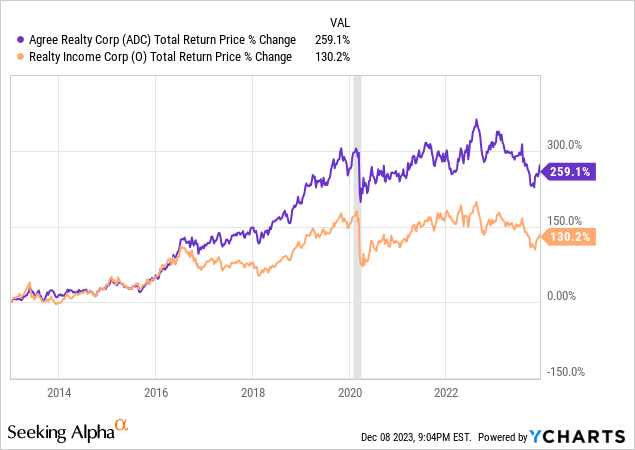

The biggest and most popular net lease REIT is undoubtedly Realty Income (O), the renowned monthly dividend payer that boasts a 28-year dividend growth streak.

But O is massive. Its enterprise value is nearly $60 billion, and its annual acquisition volume of $9 billion (this year) is itself larger than the market cap of all but two other net lease REITs. To my mind, this level of acquisition volume will necessitate O to reach well outside of its sphere of competence for acquisitions or lower its underwriting standards, or both.

Instead of O, my favorite net lease REIT is Agree Realty Corporation (ADC), a much smaller REIT that invests exclusively in the nation’s largest and strongest retailers admire Walmart (WMT), Tractor Supply Co. (TSCO), and T.J. Maxx (TJX). ADC also has a pristine balance sheet, low debt, and almost no debt maturities until 2028.

Although O has a very strong long-term track record of performance, ADC has overtaken O in the last decade in total returns — by a wide margin.

I wrote more about ADC in “Why Agree Realty Is My Largest Holding.”

In a general sense, dividend-paying companies with a commitment to keep paying and growing their dividends also do well in low inflation environments, in part because low inflation leads to low interest rates.

That’s partially why my largest ETF holding is the Schwab US Dividend Equity ETF (SCHD), which specifically targets large, stable, high-quality companies with pricing power and at least a 5-year dividend growth streak.

I gave a lot more of my dividend stock picks in several recent articles: