Web browser extensions can turn from useful to dangerous in just one update, potentially opening up your browsing habits and some personal data to an unknown third-party developer or company. It has happened over, and over, and over again, despite the best efforts from Google, Microsoft, and other browser developers. Here’s how it keeps happening, and what you can do to protect yourself.

This Cybersecurity Awareness Week article is brought to you in association with Incogni.

Browser extensions are overwhelmingly free to install. In fact, paid extensions are so rare that Google shut down the payments system for the Chrome Web Store in 2020, pushing developers to other payment systems. The few premium extensions that do exist usually have some level of free functionality, or they exist as a component of some larger paid service. For example, Microsoft Editor can fix some of your typos and grammar mistakes for free, but more advanced checking and writing tips requires a paid Microsoft 365 subscription. For services like ProtonVPN, the extension is just another client option, alongside native apps for desktop and mobile platforms.

Free browser extensions usually rely on donations, open-source contributions, or affiliate revenue to subsidize the cost and time involved with development. However, sometimes the developers look for ways to generate additional revenue without charging the user, which is where we start running into trouble.

The Downward Descent

Many extensions make money from third-party analytics and advertising platforms. The developer can add those platforms to an extension, which will then record usage data from the user (such as browsing habits) or display ads somewhere in the browser, and pay the developer based on the number of users and how much data is collected. The extension creator gets a steady stream of income, in exchange for your privacy. Sometimes the extension is just sold outright to an advertising/data company.

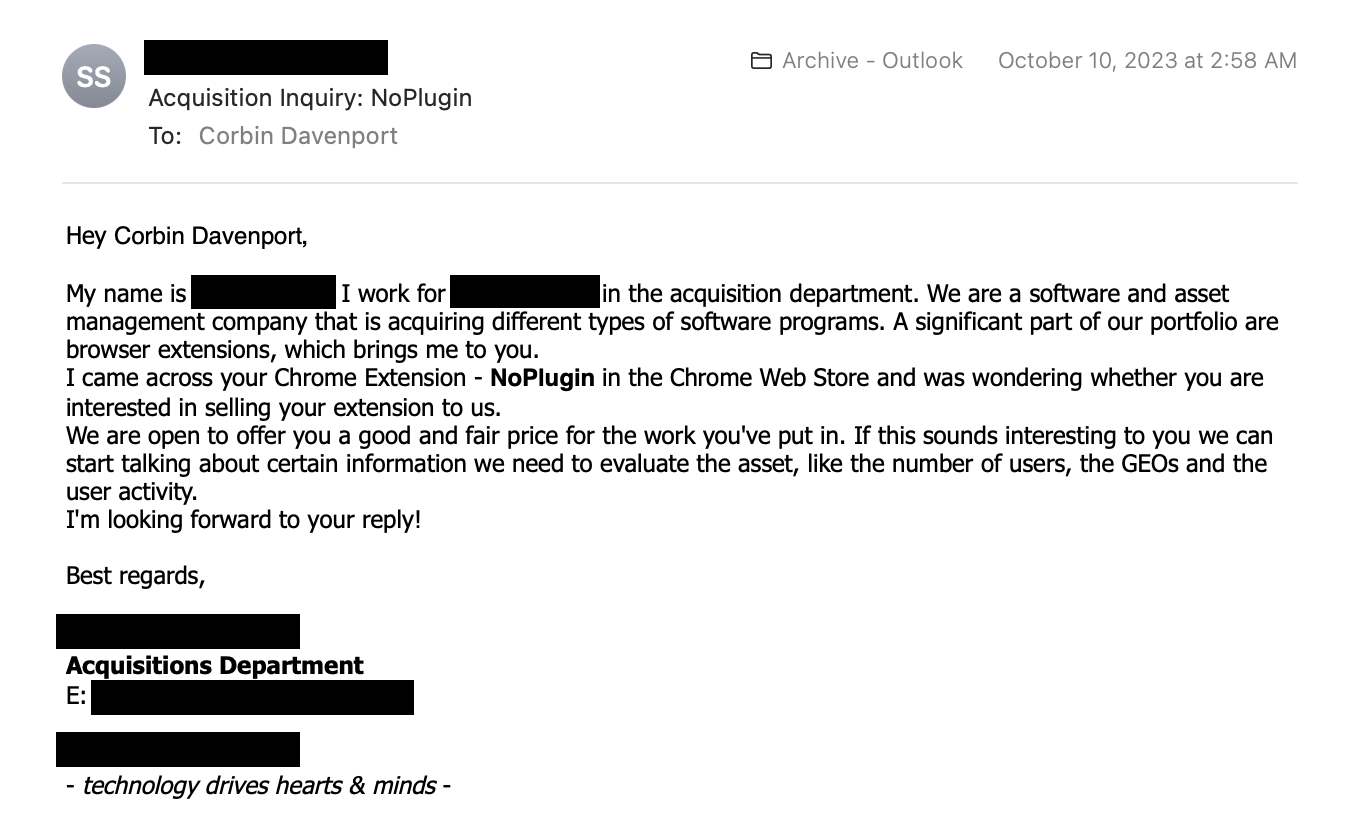

I’ve been developing browser extensions for over a decade, and over the years, I have received a steady stream of emails asking me to put tracking code in my extensions or sell them outright. In fact, I got another one while writing this article. No, really.

I’m definitely not alone. Oleg Anashkin, the developer for the Hover Zoom+ extension, has published a running list of all takeover requests for their extension on GitHub. Many of the offers are about adding code that injects affiliate links into pages, or collecting user data. One of them claimed to have “developed a new data collection technology that can be added to extensions and seamlessly records the users web surfing habits.” Some of the messages also try to reassure the developer that their code won’t get the extension kicked off the Chrome Web Store — if you have to say that, then it’s not a good sign.

Google doesn’t outright prevent this data-hoarding behavior for extensions listed in the Chrome Web Store. Extensions with ads can’t imitate browser or computer-level popups and they are required to state where the ads are coming from (e.g. an injected ad might say “From SuperCoolVPN Extension” next to it). Extensions that collect data must have a Privacy Policy that explains what data is obtained and who it is shared with. Additionally, when extensions are submitted to the Chrome Web Store, the developer has to provide an explanation for every single permission. As long as an extension is transparent about collecting data for third parties, it’s usually allowed.

However, all those policies require some level of enforcement, which means it’s possible for malicious extensions to collect some user data before Google or another browser vendor notices and takes action. In 2019, Avast and AVG’s Online Security extensions were caught recording website visit data and selling it to Home Depot, Google, Pepsi, and other companies through Avast’s subsidiary Jumpshot. In 2016, the popular Web of Trust browser extension was selling identifiable user data after claiming it was anonymous.

Why Extensions Are Different

Browser extensions are far from the only pieces of software potentially invading our privacy, but they’re one of the hardest to protect against. Many of them require access to every page you visit because that’s how they work. That’s the only way for them to add popups, new menus, check grammar in text fields, or perform other actions. Some of them can be limited to just a few websites, or only turned on as needed, but most of them require wide access to function as advertised.

If you have any browser extensions installed, make sure they’re from a developer or company you can fully trust. You might also want to consider supporting your favorite browser extensions through donations, premium features, or whatever other methods are available — if shady analytics companies become the only way extensions can cover development costs, extensions will be even less safe than they already are.