My father didn’t express his love with words but would tell me to come by “to see how the tomato plants are growing,” code for “I miss you.”

Article content

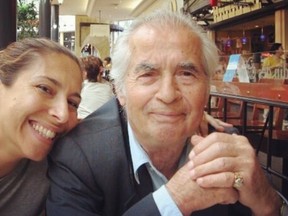

This Father’s Day will be the 11th I won’t be celebrating with my dad, who died in 2013. Time has, of course, softened the pain of irreversible loss. The thought of his absence in this world no longer cuts through me like a sharp knife. But the dull ache of longing for what is no more never leaves me. I miss him. I suppose I always will.

More than a decade later, I still think of him often and wonder what his thoughts would have been on a variety of subjects — even if we rarely agreed on anything. I’m the daughter of an immigrant dad. I wrote my first book primarily because of how tired I was of listening to political rhetoric that treats people like my parents as liabilities, threats or problems to be solved. I wanted to pay tribute to them and to that first generation who worked so damn hard to build a life here.

Advertisement 2

Article content

Ours was an imperfect and complicated relationship. Like many other immigrant dads of his generation, he had minimal education and spent most of his life toiling in restaurants, working hard, contributing in his own way to this city, this province and this country. In typical old-school Greek dad fashion, my dad wouldn’t openly express his love with words but would call me up to tell me to come by “to see how the tomato plants are growing,” code for “I miss you.”

When he died, I worried I would forget essential things about him. I feared my memory would betray me in tiny increments and I’d slowly and gradually forget the little things that made him who he was. But, as cliché as it sounds, those we love remain alive. Eleven years later, I can still hear his voice and his laughter in my head, as clear as day. Every time my sister and I come across a terrible “dad joke,” we groan and agree he would have found it unbearably funny.

Holidays like Mother’s Day and Father’s Day are strange beasts because they provide an effortless annual opportunity to acknowledge our moms and dads. But, for those who’ve lost a parent they loved, they only serve to remind us of what we’ve lost. I’ve long since moved from grief to gratitude, however. Now, when I think about my aggravating, impatient, stubborn, hard-working Greek dad, it’s often with a smile on my face.

Advertisement 3

Article content

Memories often flash in front of my eyes, like a rotation of now-faded vintage Kodachrome slides that live within me and pop up occasionally in unexpected ways. My dad in shorts and a Montreal Expos cap waving to us on a Greek beach, asking us if the water is cold. My dad, impossibly young, working in his restaurants, a proud business owner. My dad, older and frailer, with thick salt-and-pepper hair, leisurely walking — hands behind his back — repeating the same old childhood stories for me. My dad, reaching over from across the kitchen table, offering me a slice of orange, or a pinch of basil to tuck behind my ear. My dad, throwing me an annoyed sideways glance.

Writer (and dad) Ben Fountain aptly points out that “much of life, fatherhood included, is the story of knowledge acquired too late.” We’re all — daughters and fathers — learning as we go along. We don’t always get it right.

Many often talk about motherhood as a “biological calling” and point to “maternal instincts” as something innate. But, as a woman who never wanted children, I believe parenthood is ultimately a choice. A hard, glorious, hair-pulling, joyful choice that transforms your life.

Fatherhood is a choice too. And if you try your best, even if you mess up once in a while, I promise you your children will remember and miss you forever.

Toula Drimonis is a Montreal journalist and the author of We, the Others: Allophones, Immigrants, and Belonging in Canada. She can be reached on X @toulastake

Recommended from Editorial

Advertisement 4

Article content

Article content