A favorite celestial target is getting the James Webb Space Telescope treatment.

The Horsehead Nebula, a cosmic masterpiece about 1,300 light-years away from Earth in space, got its name from a portion looking like a seahorse in profile, buoyed by thick waves of gas and dust. Actually, it’s a bit of a Rorschach test: The sign of a true nerd is if you see a knight chess piece.

Other telescopes have snapped detailed photos of this object before. But now infrared cameras on the Webb observatory, a joint operation of NASA and the European and Canadian space agencies, are showing off with an extreme close-up.

The nebula, also called Barnard 33, is in the constellation Orion. The cloud is composed of other famous markers, such as the Great Orion Nebula, the Flame Nebula, and Barnard’s Loop. It is one of the closest places to our solar system where new massive stars are under construction.

The new image reveals the horse’s mane as a “dynamic region” that transitions from a mostly neutral, warm area of gas and dust to surrounding hot, ionized gas, according to the Space Telescope Science Institute. Formed from a collapsing cloud of star stuff, it glows because it’s under the spotlight of a nearby hot star.

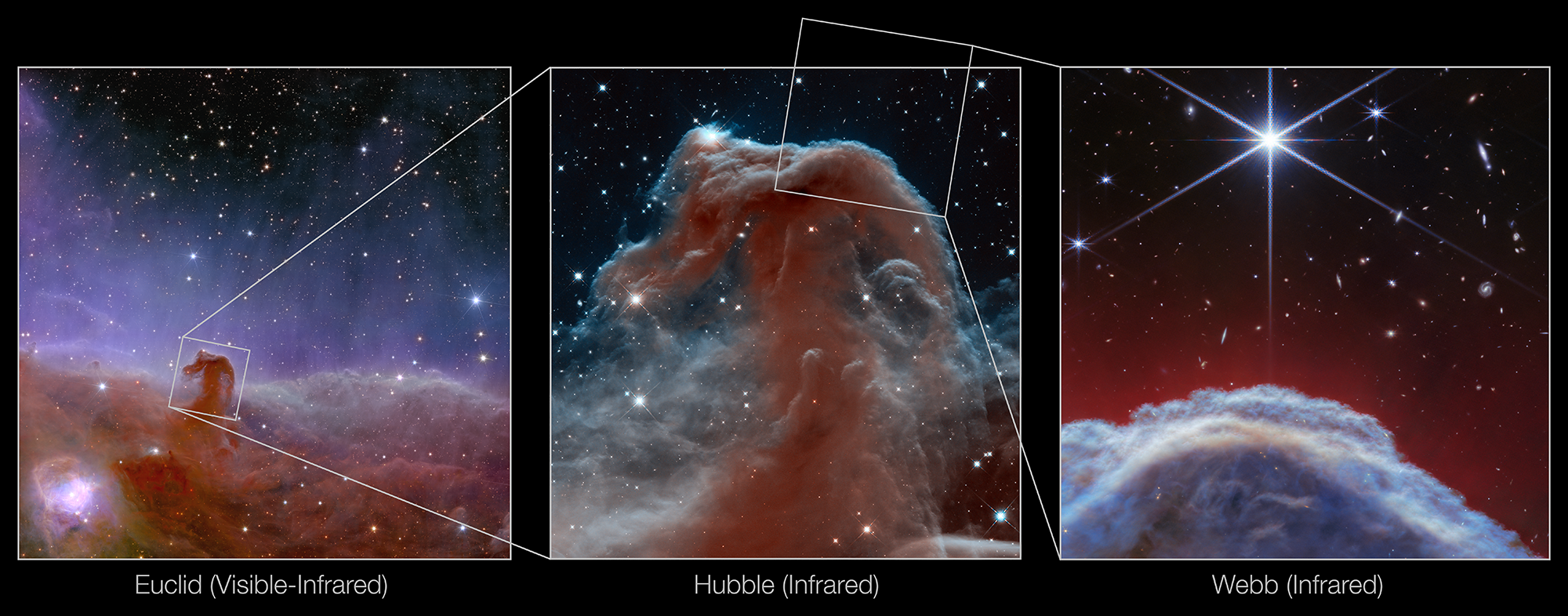

A comparison of telescope images of the Horsehead Nebula. From left: ESA’s Euclid, Hubble Space Telescope, and James Webb Space Telescope.

Credit: ESA / Euclid / Euclid Consortium / NASA / J.-C. Cuillandre / G. Anselmi; NASA / ESA / Hubble Heritage Team; NASA / ESA / CSA / K. Misselt / M. Zamani

But even now, scientists can see this iconic wonder won’t last forever. The gas clouds surrounding it have already disappeared. Though the horsehead pillar is made of denser clumps of material that aren’t as easy to erode, it too will eventually recede into the night.

Mashable Light Speed

In terms of the universe, it’ll be gone in a flash. On a human timescale, well, that’s about 5 million years from now.

This famous nebula, first discovered more than a century ago, is now well-known as a “photodissociation region,” or PDR. Ultraviolet light shining from young, massive stars makes a toasty nest of gas and dust in between the plasma (super hot gas) surrounding the stars and the clouds from which they were born. That extra dash of UV radiation affects the chemistry of the region and creates a lot of heat.

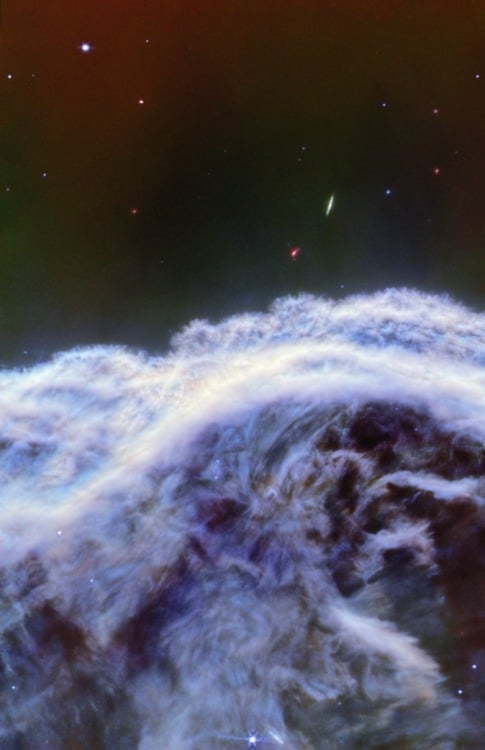

Webb telescope investigators zoomed in on the Horsehead Nebula with the mid-infrared camera, capturing the glow of dusty silicates and soot-like molecules.

Credit: NASA / ESA / CSA / K. Misselt / A. Abergel

The light beaming from such regions gives scientists a unique way to study the processes that cause interstellar matter to evolve, not just in the Milky Way galaxy, but throughout the universe.

“As UV light evaporates the dust cloud, dust particles are swept out away from the cloud, carried with the heated gas. Webb has detected a network of thin features tracing this movement,” the institute explained. “The observations have also allowed astronomers to investigate how the dust blocks and emits light, and to better understand the multidimensional shape of the nebula.”

The Webb telescope launched from Earth in December 2021, and is now orbiting the sun nearly 1 million miles away. NASA says the observatory has enough fuel on board to support research over the next 20 years.

Webb was built to see farther than Hubble, using a much larger primary mirror — 21 feet in diameter versus just under eight feet — and detecting invisible light at infrared wavelengths. In short, a lot of dust and gas in space obscures the view to extremely distant and inherently dim light sources, but infrared waves can penetrate through the clouds.

The largest chunk of Webb’s time — about one-third of the program — is spent studying galaxies and the gas and dust that exists between them.