The majority of Americans live in and around big cities, according to the US census, and in nearly all these metro areas, internet access is fast enough for casual browsing and costs about as much as other utilities. Some cities and municipalities have multiple high-speed options like fiber and cable internet, but other regions lack access to even the lowest-speed broadband.

By one government agency’s estimate, 7.2 million Americans lack high-speed internet access. Many more Americans are stuck with speeds that would have seemed slow decades ago. They’re trapped in what’s called the “digital divide,” where access is limited by infrastructure, affordability or other circumstances that cut them off from online services that most Americans take for granted.

While the lack of high-speed internet has wide-ranging consequences, one that is overlooked is the inability to stream video. It’s not just missing out on your latest shows from the growing (and merging) number of services, either: Lacking fast enough internet to watch video cuts people off from livestreamed news, digital classrooms and more. Relying on cable TV or satellite, or in some areas a small number of over-the-air channels, can be extremely limiting and a less-than-ideal substitute.

According to a Pew Research Center report, “While most adults living in rural areas (73%) subscribe to high-speed internet at home, they are less likely to do so than their peers living in suburban areas (86%) and slightly less likely than those living in urban settings (77%).”

And it’s not just urban versus rural. Income also plays a big part. The report says that 95% of adults with an annual household income of at least $100,000 subscribe to broadband. This compares with 57% of adults in households that make less than $30,000 per year, which is less than half the US median household income of $74,000.

Getting those millions of Americans access to high speeds for video streaming, online education, telehealth services or running a business is largely a funding issue. In some cases it’s needed to build out broadband infrastructure, in others it’s a renewal of programs that help keep the costs of internet service down. Which is to say, the lack of broadband goes deeper than just an inability to watch the latest Marvel show, and finding a solution isn’t as simple. Here’s why.

The problem

Not everyone has lots to watch. OK, no one does really, but some have even less than others.

Many people don’t give much thought to internet speeds. Usually it just works, and there’s no reason to question it. Pretty much every internet user experiences occasional speed-related issues, like pauses in videos, drops in resolution, stuttering and buffering, though they may be too infrequent to matter. Those who lack access to reliable and fast internet speeds have those issues and more.

It’s easiest to think about internet bandwidth like a pipe full of water. For someone living in a well-served metro area like New York or LA with 1 gigabit per second fiber, it’s a huge pipe. Anything in their home that requires some amount of that water (aka data from the internet) can tap into the flow without limiting other devices. So if the pipe is big enough for a household with a family, the daughter can download a new game on her gaming PC, dad can play a console game online with his friends and mom can watch Netflix, all at the same time with no slowdown or other issues.

For someone living in Columbia, Missouri, for example, the pipe is much smaller. Everyone online still wants to siphon the same amount of “water,” but there’s less to go around — so all that internet activity slows to a crawl. Compared to the 1Gbps speeds in metro areas, residents of Columbia get a median download speed of 21.3Mbps, according to the publication High Speed Internet. Factoring those speeds into our example, the daughter’s download slows to a crawl, so now her game won’t be ready to play until tomorrow. Dad’s online game is choppy, laggy and he often gets disconnected. Mom’s Netflix is so low-resolution it’s practically blurry and it stutters. It might be possible for a home’s slow internet to handle one of these activities at a time, but certainly not all at once. Ever been in a house where the water pressure drops when someone flushes a toilet? Same idea.

All streaming services have minimum speed requirements, but that’s assuming only one person in the house is watching. Multiple devices streaming different content increase that requirement.

Around 36% of TV viewing is now through online streaming, according to a November 2023 report by the Leichtman Research Group. But with so many of life’s leisure activities, remote work and cultural conversations only available online, the lack of bandwidth is an issue that goes beyond missing entertainment. How about the inability to take part in online classes like millions of other students? Or not being able to video chat and stay connected with loved ones, especially seniors aging in place? The lack of internet, or the restrictions of slow internet, leaves a sizable segment of the population living outside the modern world.

How much speed does the average household need? The Federal Communications Commission’s baseline for broadband of 100Mbps at a minimum is a good target, which can handle simultaneous activities like streaming 4K video at 35-50Mbps, online gaming at 25-35Mbps, social media at 10Mbps, and so on. Many households can’t get anywhere near these minimums. According to the FCC, 4.7% of US households (roughly 6.2 million) don’t have any providers for even 24Mbps internet, a number that increases to 8.9% if you exclude wireless options like 5G home internet. The lack of high-speed internet disproportionately affects rural areas, with 17.7% of households lacking even this older definition of broadband and 28.9% lacking the option for 100Mbps speeds.

To pile on to the issue, cost is another huge factor. In some cities there’s at least a modicum of competition between internet providers, theoretically improving service and keeping prices in check (though not always). Even if a city has pricey internet, it’s almost always cheaper per gigabyte than in rural areas. What’s considered “high-speed” there might be below the slowest tier in a bigger city, yet be priced like that city’s highest plans. In both cases, the cheapest plans might be too high for anyone on a tight budget, and subsidies are about to get harder to secure with the government’s Affordable Connectivity Program running out of funding in April. The lack of competition also affects this, with the FCC finding 40% of households only have one local provider that supplies 100Mbps broadband.

Data caps further limit internet accessibility. A rural area might have speeds that are reasonable, but limit the total amount of high speed data you can use each month. Many people are familiar with this kind of data cap on their mobile plans, but in some areas there are similar limits on home internet. For instance, satellite internet provider Viasat promises up to 150Mbps respectively for its nearly nationwide US coverage, but, “If your data usage is trending to exceed the ‘typical usage’ of a residential user on our network, you may have reduced priority during times of network congestion resulting in slower speeds.” They classify anything more than 850GB as not typical, so downloading more than that in a month could lead to throttled speeds.

Another regional internet provider example, Vyve Broadband, has a 1,000GB-per-month limit on their slower and less expensive plans, but increases that for more expensive plans. You’d be amazed how quickly a normal household can hit a data cap if they want to stream video, download and play games, video chat, scroll TikTok and so on. Though it varies per service, streaming video in 4K can be around 2-3GB of streaming data per hour. If four people are watching different shows in different rooms, that’s upwards of 12GB per hour. If they all watch five hours a night, you’d hit these caps well before the end of the month with streaming alone. If they’re on their phones at the same time, as we all are, they’ll reach the cap even sooner. After that, subscribers should expect to encounter slower speeds or fees, depending on the internet provider.

The bigger issue, and some hope

You would think that the move to 4K TVs, and growing amounts of 4K content, would have started causing problems even for people who aren’t bandwidth-restricted. 4K TVs have four times as many pixels as HDTVs, so it’d be natural to assume 4K video requires four times the bandwidth compared to 1080p HD. Thankfully, that’s not usually the case. Most 4K content uses a different compression tech, or codec, than the majority of older HD content. So in many cases high-quality 4K video can require less bandwidth than high-quality HD video using the older codec.

HD with the new codec results in even lower data rates. Netflix, for example, uses AV1, which is more efficient than the older codecs used in the early days of HD and 4K. So, all else being equal, platforms using the latest compression tech require lower internet speeds to watch streaming video at the same quality compared to when they used older codecs.

720p will look fine on a phone or tablet. 1080p will look fine on a TV. 4K will look great on a 4K TV, but is overkill for smaller screens.

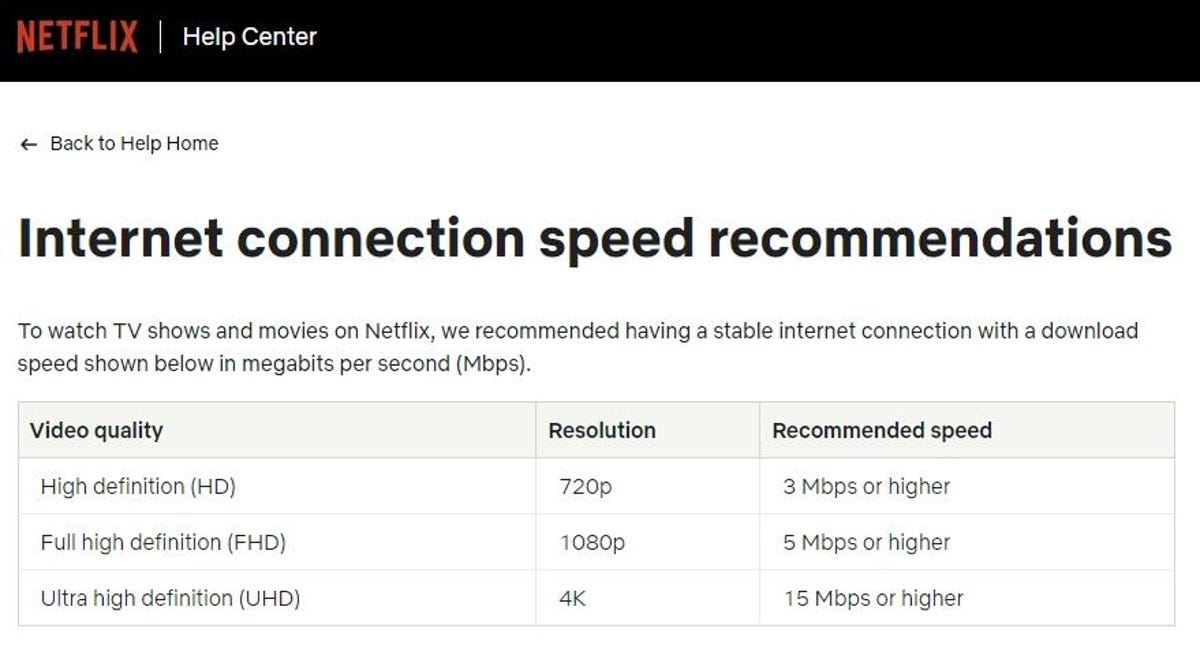

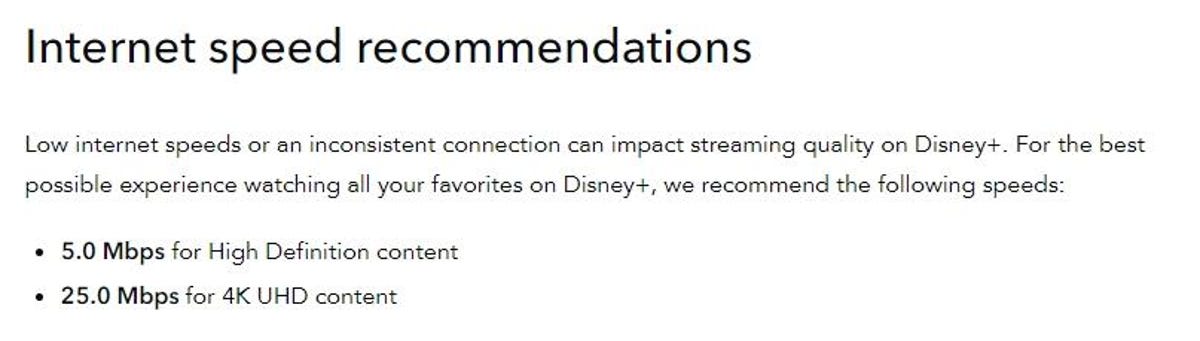

That said, internet speeds can only go so low before lagging and buffering ruins the experience. To that end, all the major streaming services have minimum speed requirements. In the case of Netflix, it’s 3Mbps for 720p, 5Mbps for 1080p, and 15 and higher for 4K. For Disney Plus it’s 5Mbps for HD, but even more for 4K: 25Mbps. For Max it’s even higher, with a minimum requirement of 25Mbps for 4K HDR, and a recommended 50Mbps. On the other hand, Amazon Prime Video can go down to 1Mbps, but that’s just for SD video (aka 480p), which might look OK on a phone but will be very soft and “blurry” on a TV.

There’s not a lot the providers can do to improve this, beyond using better codecs when possible, and there’s a limit to how much better these codecs can get. Building server farms closer to remote areas won’t really help, since the “last mile” to connect broadband to households is one of the biggest bottlenecks to streaming speeds. More fiber is laid every year, and states will get a boost to their fiber footprint once funding from the $42 billion Broadband Equity Access and Deployment program gets sent out to each state to build connectivity infrastructure — but that might take years, leaving some Americans unconnected. To continue the pipe comparison from earlier, it doesn’t matter if everywhere else is connected via 30-foot-wide water mains, if you’re connected to the pipe with a garden hose, all you’re going to get is a trickle.

That said, all the providers want to serve video that people like watching, so this is something they’ve continually worked on. In some cases, it’s possible for individuals to set their own limits on how much data a service uses.

In the last few years there have been promising improvements pledged to get high-speed internet to as many people as possible with both fiber funding and broadband alternatives. The BEAD program is part of a $65 billion slice of the massive $1.2 trillion 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that’s dedicated to closing the digital divide to help all Americans get better, faster and more affordable internet. The 2021 American Rescue Plan Act, one of the big COVID-19 relief bills, also has some funding left to spend on connectivity.

Some of this funding can be applied to alternatives to traditional wired internet. Companies like Verizon, T-Mobile and Starry offer home internet using 5G mobile networks, with some plans as low as $15 a month. While rural areas might lack 5G coverage, it’s a lot easier, and therefore cheaper, to improve the performance of mobile networks compared to running physical wires to remote and distant houses. One new transmitter tower could supply a home with much faster internet, assuming it maintains a steady connection.

Home internet that uses mobile networks is becoming more widespread.

Then there’s internet beamed from space, literally. It’s certainly not cheap, but services such as SpaceX’s Starlink satellite internet can offer reasonably fast speeds that could be the best, or only, option for some areas that are too far from wired deployments or 5G towers.

Like all technology, internet connectivity progresses with time. While slow and often with periods of stagnation, internet speeds all over the country have steadily increased — so much so that the FCC’s 100Mbps download and 20Mbps upload baseline is a recent quadrupling from its prior minimum of 25Mbps download. Internet service providers have no choice but to catch up, meaning a rising tide is coming for folks still struggling to stream video.