While the March FOMC meeting may spark some intra-day, or intra-week, volatility for the financial markets, the decision itself seems unlikely to be a game-changer from a bigger picture perspective, with the broader direction of policy set to remain unchanged, as the policy backdrop remains supportive for risk.

What the FOMC do this week doesn’t really matter in the grand scheme of things.

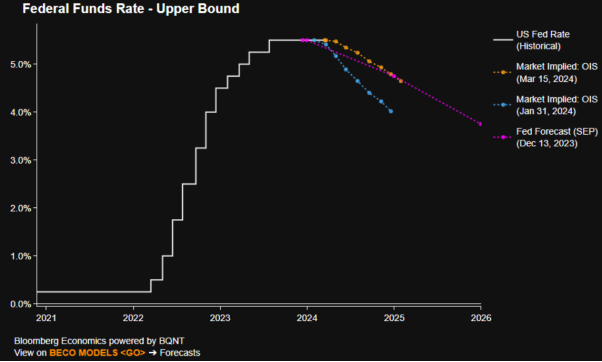

That’s not to say the decision, and latest Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), won’t be interesting. They will, particularly whether recent hotter-than-expected inflation figures are enough to see a modest upward revision to the PCE/core PCE forecasts and, of course, whether the updated ‘dot plot’ comes with any revisions to the December iteration – chiefly, whether the median ‘dot’ again points to 75bp of cuts being delivered this year.

With that said, it is only a hawkish risk, and not the base case, that either of those two shifts are made. In any case, even if the median 2024 dot is nudged 25bp higher than a quarter ago, it seems unlikely that such an adjustment would be a game-changer in the grand scheme of things, besides causing some short-term vol in front-end rates, and likely also knocking equities lower, and giving the greenback a renewed kick higher.

More broadly, the direction of travel that policy is set to take this year should remain broadly unchanged. While the FOMC will remain in no rush to cut, likely reiterating a need to maintain restriction until ‘confident’ that inflation is on its way back towards the 2% target. In other words, continuing to play a data-dependent waiting game.

Of course, this data has been somewhat mixed of late. Headline inflation is beginning to trend in a worrying direction, with CPI having printed hotter-than-expected for three months running, and seemingly having found a floor around 3% YoY. Supercore inflation (services, ex-housing) is also moving in the wrong direction, having remained north of 4% YoY for two months running. While disinflation continues – with February core CPI continuing a streak of monthly declines that begun in mid-2023 – the process is clearly much slower, and much bumpier, than policymakers would desire.

The rationale behind a wish to be patient in firing the starting gun on the easing cycle is being borne out in current data, with the ‘last mile’ back to 2% increasingly looking like the most difficult.

At the same time, while headline payrolls growth remains resilient, with the 3-month average of job gains sitting at +265k, the highest since last June, signs are beginning to emerge that the labour market may be beginning to rollover – unemployment surprisingly rose to 3.9% last month, while participation remains somewhat shy of the cycle highs seen in Q4 23, at 62.5%.

The problem for policymakers is that it is still too early to tell whether what we are looking at here are data anomalies, or data trends. Naturally, a couple more months’ worth of figures will be needed in order to confidently answer those open questions.

We remain, then, in something of a monetary policy purgatory, and likely will no matter the outcome of the March FOMC meeting. The direction that monetary policy is set to take this year should remain unchanged – cuts are on the way, and an end to quantitative tightening is also due shortly, with both likely to begin in the summer, probably in June.

Importantly, this is a data-dependent waiting game that will play out with the FOMC sat, ready and waiting, to act if they see a need – either due to a sudden turn in the labour market, more rapid than expected disinflation, or some kind of financial accident.

In other words, while markets continue to hang on every remark that FOMC members make in public, the Fed put remains in place, leaving an insurance policy for both markets, and the economy more broadly. This should, in turn, continue to underpin risk, and allow dips to be well-bought and limited in magnitude, with investors again confident that the Fed ‘has their backs’.

Put simply, what matters is not what the Fed do this week, or even exactly when they do eventually deliver the first rate cut. What matters is the broader path that policy will take this year; i.e., a looser stance, coupled with the optionality to deliver more aggressive support if it proves necessary. Two powerful factors that should limit the extent of equity downside for some time to come, and keep the path of least resistance leading higher.iew