The Sunday Magazine23:58Action movies rule the box office. So why isn’t there an Oscar for stunt people?

In 2020, a stunt double strode on stage to accept Hollywood’s biggest award.

The thing was, the Oscar was handed to Brad Pitt for playing a stuntman in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood — not being one.

“Isn’t it amazing that an actor who plays a stuntman can win an Oscar? But yet being a stuntman, you can’t win an Oscar,” said Jack Gill, a Hollywood stunt coordinator who for decades stunt doubled in TV shows and movies, including for John Schneider in The Dukes of Hazzard and Will Ferrell in Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby.

For over 30 years, Gill has lobbied the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to include a stunt category in its annual awards show, which takes place March 10 this year.

“Action in films has been a mainstay in the business since its early existence,” he said. “If you took the chariot race out of Ben-Hur, would it have been the same movie?” he said, referring to the 1959 drama.

Supporters of a stunt Oscar say it’s more important than ever for the Academy to acknowledge the contributions stunt people make to the movie industry. In recent years, the box office has been dominated by action heavy films.

In the decades since Gill started lobbying for a stunt Oscar, his petition has gathered star-studded support, including from Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg and Helen Mirren. Today, Gill has close to 133,000 signatures.

But none of his efforts appear to have made a difference.

“To not even be in the show is the tough part,” he said.

“Sometimes we’re on these films for eight months, and then to see all your other peers go up on the stage and accept, and you’re sitting at home watching it on the TV.”

Decades-long discussions with Academy

Gill points to the feature Mad Max: Fury Road as a perfect example of how the stunt industry is overlooked.

In 2016, the film was nominated for 10 Oscars, winning in six categories, including best costume design, best makeup and hairstyling, and best film editing.

But the man behind all the stunts, Guy Norris, “obviously was not nominated.”

Gill, who designed stunt sequences for movies such as The Cannonball Run, Date Night, and the Fast & Furious franchise, says the Academy has given him an array of arguments against a new category over the years, including the sheer length of the live show.

He counters that the award doesn’t even need to be given out during the televised show.

“It could be in a hallway somewhere.”

Gill acknowledges the Academy has raised concerns over safety.

“They said, if we give you an award, what’s going to keep action designers from going out there and creating these enormously huge stunt sequences just to get an award and people get hurt?”

But he points out one of the jobs of a stunt coordinator is to keep people safe on set. And he argues handing out an Oscar for special effects hasn’t caused anyone in that field to take more risks. Plus, he says, the stunt business already has the Taurus Awards, its own industry-specific prize.

“I’ve gotten so many reasons why over the 32 years that I’ve been doing this that [the Academy] stopped giving reasons anymore because they just can’t think up anything else.”

The Academy is also notoriously reluctant to add new categories. Earlier this year, the organization introduced a new category for best achievement in casting — the first new award since 2002 — which will be presented at the 2026 Oscars.

Secrecy shrouds stunts

Edmonton-born stunt co-ordinator Monique Ganderton says there might be a reluctance to lift the curtain on the role of doubles because it could spoil the Hollywood magic if audiences see their favourite action stars not doing all the action.

Stunts have “historically been a secret.”

As Marvel Studios’ first female stunt co-ordinator, Ganderton designs and oversees all the stunts on any given movie. Yet even her own mother “didn’t know what I really did for a living.”

It wasn’t until her mom got a job in the props department on the same Vancouver film set where Ganderton was working that she realized the sort of risks her daughter was taking.

Protective barriers were being erected for the crew to get behind because “we were going to blow all this stuff up,” Ganderton recalled.

And while everyone was getting pushed “like a block away,” Ganderton was preparing to be in front of the camera — and the barricade.

“I actually had to be like, ‘Mom, you have to bring me my grenade launcher. And she looks at me and she’s like, ‘Oh my God, this is what you do?'”

Oscar snub stings given industry risks, says choreographer

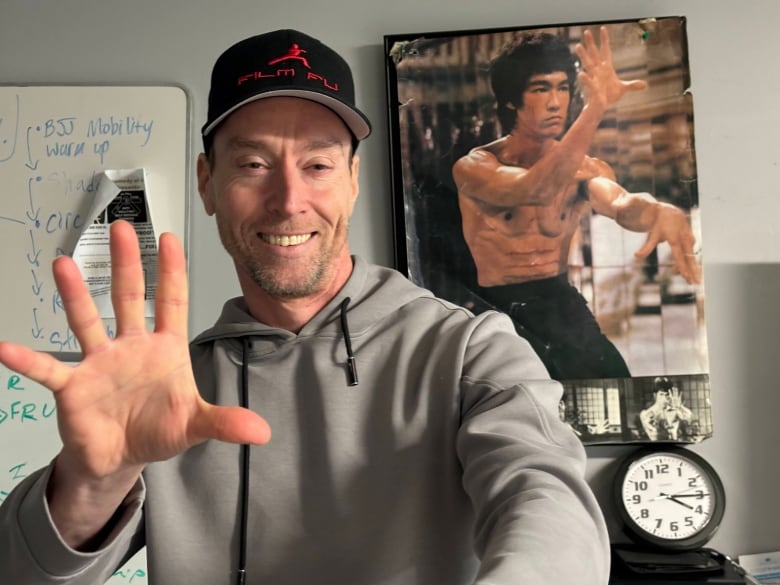

Kirk Caouette, an experienced stunt coordinator who teaches fight choreography in Vancouver, says the risks stunt performers face in the name of entertainment make the lack of a stunt Oscar plainly a snub.

Gill has severed a finger that was reattached, punctured lungs and broken his back from jumping off cliffs, exploding boats and performing high-speed car chases.

Ganderton has leaped between galloping horses, jumped through windows, and been set on fire for stunts.

Caouette, who began his career doing stunts, including doubling for Alan Cumming in Marvel Studio’s X2, has broken both legs, an arm and a rib.

He gets emotional when he talks about a close friend who was performing a stunt in Vancouver when a safety wire failed and he fell more than eleven metres.

“It was really a miracle that he lived. It was awful,” Caoette said.

In an email to CBC, the Academy said “stunt coordinators are a deeply respected part of our membership,” and noted that historically, new awards evolve from the Academy’s 18 branches.

Stunt performers only became part of a newly-created production and technology branch last year. The move has made Gill more optimistic about achieving a stunt award than he has been in years, but he says the branch is not solely dedicated to stunt people. It includes script supervisors and associate producers. And everyone is vying for their own award.

Caouette says the fact that the 2024 Oscars will once again overlook the contributions of the stunt industry is upsetting.

“We risk our lives for this industry.” He thinks of the sacrifices his friend made and of others who were killed on the job. In 2017, a stunt woman died on a Vancouver film set while shooting an action sequence.

“And yet it’s more important for them to pretend we don’t exist than to acknowledge our existence,” he said.