Some residents of a mining town in northern Quebec tell CTV W5 they no longer want to reap the financial benefits from heavy industry, if it means the price they have to pay is their health.

For years, a copper smelter at Rouyn Noranda, 600 kilometres northwest of Montreal, has been spewing a cocktail of heavy metals into the air.

Residents wonder whether cadmium, lead, mercury and arsenic are emitted in dangerous amounts and poisoning those near the Horne Smelter, owned by international conglomerate Glencore.

The smokestacks of Canada’s only copper smelter have been pumping out pollution at Rouyn Noranda for nearly a century. Rouyn Noranda is known as a quaint town with lively arts culture and festivals.

People living closest to the smelter have higher cancer rates, a shorter life expectancy and a higher proportion of underweight births than the average Quebecer, according to a 2022 study by Quebec’s Institute of Public Health.

But Marie-elise Viger, Glencore’s environment manager, says the smelter isn’t the source of dangerous levels of pollution.

“The levels are on the normal side,” Viger told W5. She says she moved from Montreal to Rouyn Noranda nearly 15 years ago. “It’s a safe environment. So I feel very comfortable … raising my children here.”

In 2011, Quebec set a safety standard capping arsenic emissions from plants at 3 nanograms per cubic metre — the strictest limit in the world.

Glencore surpasses the limit, emitting at least 15 times that amount. Its smelter has an exemption based on a grandfather clause. Quebec approves how much the smelter emits each year.

Glencore’s Horne Smelter has for years been spewing a cocktail of heavy metals into the air. (W5)

Glencore’s Horne Smelter has for years been spewing a cocktail of heavy metals into the air. (W5)

Some suffer health issues

Residents have long feared living near the smelter exposes them to harmful levels of chemicals like arsenic.

Mireille Vincelette is one of them. She wonders if the smelter’s pollution is to blame for her asthma.

“When I go out running and the air quality gets bad, I have difficulty breathing,” Vincelette told W5. “I have to come back and take my puffers to continue.”

Dr. Koren Mann, a professor at McGill University in Montreal, has proposed a study to examine lung cancer rates in Rouyn Noranda and patients’ possible exposure to metals in the air, including arsenic, a human carcinogen.

“It actually seems like the smoking rate is lower. So you would potentially expect fewer … lung cancer cases than what we see,” he told W5. “So there’s probably something else going on. And we’re going to test the hypothesis that it’s the metals that are contributing to that.”

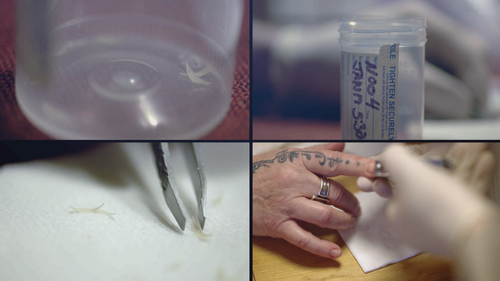

Quebec Public Health tested the nails of children living near the smelter in 2019.

Vincelette’s son, then aged two-and-a-half, had nails with four times more arsenic than in children who lived in a nearby community. Her daughter’s nails showed it had 13 times more arsenic.

“It was a shock,” Vincelette said. “I feel guilty of raising … my children here. But after that I was mad at the government. I was thinking they were protecting us and I was very mad they didn’t.”

Overall, levels in children growing up next to the Horne Smelter were up to four times higher than children living in a nearby town.

Mireille Vincelette says she has difficulty breathing when she goes out running and wonders if a copper smelter’s pollution is to blame. (CTV W5)

Mireille Vincelette says she has difficulty breathing when she goes out running and wonders if a copper smelter’s pollution is to blame. (CTV W5)

History of smelter

The site was a forest before a prospector struck gold in 1921. A company called Noranda started operating there and gave its name to the town it founded.

The Rouyn Noranda smelter is an economic powerhouse, pouring $500 million into Quebec’s coffers each year.

Although metal deposits dried up and the mine shut down, the smelter continued operating. Glencore bought the company in 2013.

Today, 15 per cent of the Horne Smelter’s production involves refining copper from electronic waste like old cellphones. The recycling process emits hazardous by-products, according to experts.

“The problem is that when you take the copper out, then your leftovers or the stuff that’s there is not necessarily stuff you want to keep,” Mann said. And in the case of the Horne smelter, some of that ends up going up into the air, and distributing around in the neighbourhoods in the area.”

A 2019 Quebec study found that levels of arsenic in children growing up next to the Horne Smelter were up to four times higher than children living in a nearby town. (CTV W5)

A 2019 Quebec study found that levels of arsenic in children growing up next to the Horne Smelter were up to four times higher than children living in a nearby town. (CTV W5)

Study mobilizes residents

In 2022, a study on arsenic levels in the bodies of children living near smelter included even more explosive information that residents were never told until it was leaked to the media.

Dr. Horacio Arruda, then the public health director for Quebec, removed a section of the study before publicly releasing the results. It detailed a hypothesis that there could be significantly more cases of lung cancer over a 70-year period because of emissions. He said at the time that the section was removed because it should be included in a separate, more comprehensive study at a later date. That study was done two-and-a-half years later.

Vincelette, who has lived in Rouyn-Noranda her entire life, decided to create Aret. The group aims to push the Quebec government and the smelter to find ways to cut emissions rather than close the plant. “I cannot leave the kids in the school getting exposed like that,” she said. “I had to do something.”

Meanwhile, dozens of residents are campaigning to clean up the air around the copper smelter.

And both the Quebec government and Glencore are named in a class action suit that lawyer Karim Diallo is preparing on behalf of residents, though it is difficult to prove someone has cancer because of the smelter.

“We’re not claiming physical injuries. We’re not claiming for a cancer, per se,” Diallo told W5. “We’re claiming for the emotional damage … the fact that you live there puts you at a higher risk and for the fact that you weren’t provided with the information in a timely manner, when they knew they were exposed. They were exposing the citizens to such levels.”

The lawsuit alleges the company knew about the harmful arsenic emissions and didn’t share that information with residents soon enough.

“Glencore could decide to, you know, really tackle the problems and reduce the emissions,” Diallo said. “They could do that. And that would help solving the problem.”

Quebec Premier Francois Legault, Environment Minister Benoit Charette and Public Health Minister Christian Dubé all declined W5’s interview requests.

As the backlash over arsenic emissions reached its peak in 2022, Glencore pledged to lower levels to 15 nanograms by 2027 with a major $500-million investment.

Vincent Plante, company general manager, says the smelter is a source of pride for the community. He also points out that the smelter employs about 650 people, mostly residents of the town. “The Horne Smelter is part of the DNA here of the city. Everything started here with the smelter,” said Plante.

Plante says Quebec public health studies that showed high levels of arsenic in fingernails should be taken with a grain of salt. He notes that older studies have shown levels are acceptable and better testing is now needed.

“Today, there is no scientific or any data that can correlate impact on the health of the people,” he said. “And we’re confident that there is none as we speak. But this is why again that we advocate the fact we need to continue the bio monitoring campaigns.”

Watch W5’s documentary ‘Arsenic Air’ Saturday at 7 p.m. on CTV