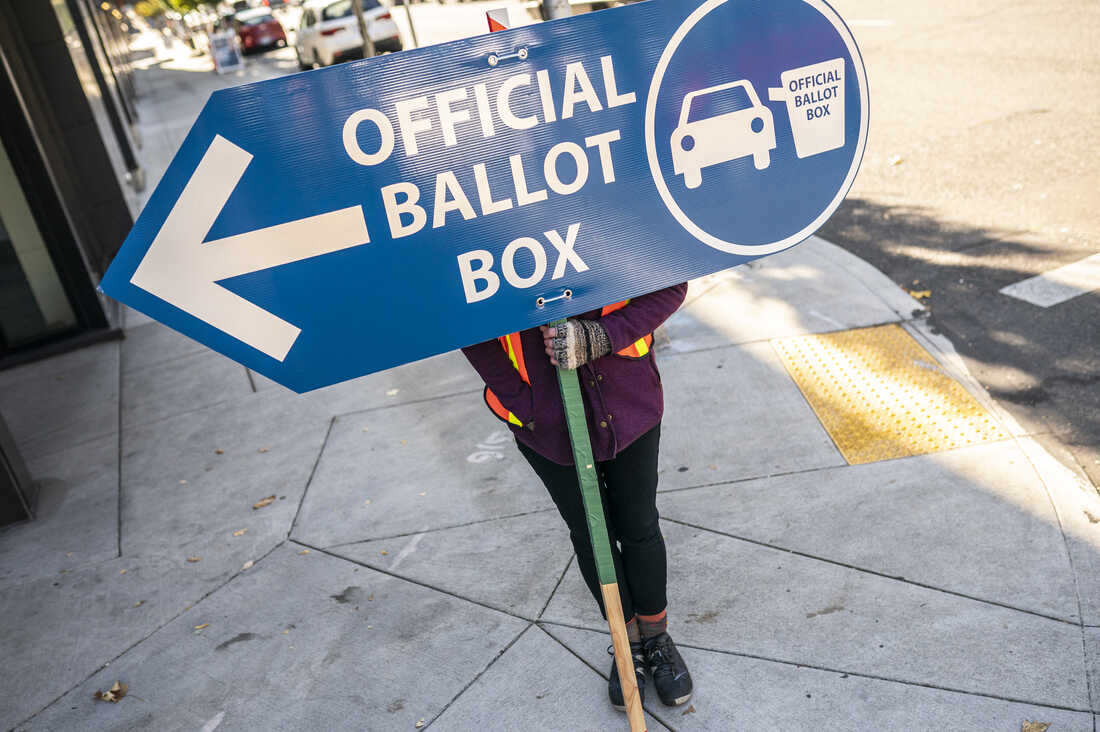

An election worker directs voters to a ballot drop-off location in 2020 in Portland, Ore. Oregon is among the states waiting for the Biden administration to greenlight plans to automatically register eligible voters when they apply to enroll in Medicaid.

Nathan Howard/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Nathan Howard/Getty Images

An election worker directs voters to a ballot drop-off location in 2020 in Portland, Ore. Oregon is among the states waiting for the Biden administration to greenlight plans to automatically register eligible voters when they apply to enroll in Medicaid.

Nathan Howard/Getty Images

Officials in several states are waiting for the Biden administration to greenlight proposals that advocates say could enable hundreds of thousands of lower-income U.S. citizens and citizens with disabilities to vote.

Despite multiple inquiries from members of Congress over the past two years, Biden officials have yet to weigh in on plans for using Medicaid application information to automatically register eligible voters when they sign up for the government-sponsored health insurance.

Biden officials have cited concerns about the confidentiality of Medicaid applicants’ information, but the delay by an administration that has said its policy is “to promote and defend the right to vote” is frustrating state officials who are eager to help more citizens participate in the democratic process — including in crucial 2024 elections.

“It is a lost opportunity. It would be great to have a way to systematically reach all these people,” says Molly Woon, Oregon’s election director.

What automatic voter registration through Medicaid could look like

A growing number of states automatically sign up eligible voters at local DMV offices.

Building on that momentum, some states have also been focusing on what more could be done at their agencies that run Medicaid, a joint federal and state program.

Since 2019, states including Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Minnesota, Oregon and Michigan, plus Washington, D.C., have passed laws calling for their Medicaid offices to transfer information about Medicaid applicants who are eligible to vote so that election officials can automatically register them.

Helping eligible voters register is not a new role for these agencies.

For decades, the National Voter Registration Act of 1993, also known as the “motor voter” law, and federal regulations have required state Medicaid offices to provide voter registration forms and then hand the completed ones over to state election officials.

But for each of the past two national election cycles, states reported that less than 2% of the registration applications they received came from public assistance offices such as Medicaid agencies.

Advocates of automatic voter registration say there are missed opportunities to make Medicaid applicants’ lives easier.

“The number of folks getting registered through Medicaid systems is minuscule. And I think it’s time to sort of admit that the way we’ve been doing NVRA compliance is not working anymore,” says Sam Oliker-Friedland, a former voting rights litigator at the Justice Department who now heads the Institute for Responsive Government, which recently led a letter calling for the Biden administration to support automatic voter registration at Medicaid offices. “What it boils down to is the government is just not using the information that they’re collecting as efficiently as possible.”

The information needed to register a voter — including their name, address, date of birth and verification of U.S. citizenship — is also collected when most adults apply for Medicaid benefits, a process that typically has to happen every year. State Medicaid agencies automatically transferring this data to election officials could not only streamline the voter registration process, but also provide timely updates that keep voter rolls clean, advocates say.

Jamila Michener, an associate professor of government and public policy at Cornell University, who is an expert on Medicaid, sees it as a potential solution to a long-standing problem with U.S. democracy.

“We think about democracy as one person, one vote, and we think about the ballot as somewhat of an equalizer. You might have $1,000,000, and I might have $1 to my name, but we can both show up and vote,” says Michener, author of Fragmented Democracy: Medicaid, Federalism, and Unequal Politics. “The problem is that that’s not what happens in practice. And because elections are our way of signaling our preferences around policy and other things, when certain segments of the population are systematically being left out of elections, it means that they’re not signaling their preferences. They, in many ways, are more vulnerable to policy. They’re more affected by what happens, but their voices aren’t shaping what happens.”

Michener’s research suggests that compared with people not enrolled in Medicaid, Medicaid enrollees are significantly less likely to vote, register and participate in politics more generally.

“They may be working and unable to get to the polls. They move more often, so their registration is less likely to stay updated,” Michener explains. “There are all sorts of barriers for people who are living in or near poverty and who are low income.”

And they make up large numbers of eligible voters who, advocates say, could benefit from automatic voter registration. In Colorado, there may be some 755,000 Medicaid enrollees who are eligible to vote and not yet registered or may need their registration updated, the Institute for Responsive Government estimates. And in Oregon, some 171,000 Medicaid enrollees make up about 85% of the state’s eligible but unregistered voters, according to state officials.

The sticking point is data confidentiality

Woon, Oregon’s elections director, says she and other state officials are ready to start designing a program — as soon as the state’s Medicaid agency gets approval from federal officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The sticking point is Medicaid’s confidentiality protections for an applicant’s information.

A state Medicaid office automatically transferring an applicant’s information to another state agency for something that’s not directly related to Medicaid without first asking the applicant to opt in runs into uncharted territory.

In 2020, Massachusetts started a program that state officials say gets around this issue by relying on a Medicaid applicant to identify themself as an eligible voter and then asking whether they want their information to be used to register them to vote.

But many advocates of automatic voter registration say it would be more efficient and secure for state Medicaid offices to determine whether applicants are eligible voters and then automatically transfer that data to state election officials to get them registered. Any applicant who does not want to be registered would be able to opt out after the data is transferred.

These are processes that Woon acknowledges would take some time and coordination to work out while protecting the confidentiality of Medicaid applicants’ information.

“I understand people get sensitive when you start talking about medical privacy, but we are only interested in the information that would indicate whether a person is eligible to vote or not,” Woon says.

What Biden officials have said about automatic voter registration via Medicaid

Still, Biden officials have yet to clarify whether they would approve some kind of automatic voter registration program at state Medicaid offices.

Jonathan Blum, the principal deputy administrator and chief operating officer for CMS, did not provide a timeline for any potential guidance to states but said in a statement to NPR that “CMS is considering additional opportunities to enhance Medicaid’s role in promoting voter registration while also ensuring compliance with Medicaid confidentiality requirements.”

Democratic senators from Oregon and Colorado have tried to press CMS for answers.

Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, the administrator for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, is seen in 2022. Officials in some states have pressed CMS for answers about plans to expand voter registration via Medicaid.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

In a 2022 letter replying to Sen. Michael Bennet of Colorado, Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, the administrator for CMS, noted that the agency had previously concluded that Colorado’s proposed automatic voter registration system “appears to be inconsistent with the Medicaid privacy protections in current law and regulations.”

But Brooks-LaSure also signaled that CMS may have reconsidered that position after President Biden’s 2021 executive order directing federal agencies to promote access to voting, adding that CMS recognizes “the importance of state Medicaid agencies assisting in expanding voter access and registration activities for the populations they serve.”

Asked whether Biden supports these automatic voter registration proposals, the White House’s press office referred NPR’s questions to CMS’ parent agency, the Department of Health and Human Services.

HHS has also been under pressure for its delayed public response to calls to add a question about voter registration to applications on HealthCare.gov, where people can apply for Medicaid. In a statement to NPR, Sara Lonardo, a spokesperson for HHS, said that “CMS continues to actively explore” adding the question in time for the next open enrollment period, which begins on Nov. 1, four days before the last day of voting for this year’s general elections.

“The Department of Health and Human Services made a commitment to advance the Biden administration’s goal to expand voting access, and it has a powerful opportunity to deliver on this commitment by offering voter registration information within the HealthCare.gov application,” Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who has led multiple letters to HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra, said in a statement to NPR. “After years of delay, HHS must follow through on its commitment and take action.”

Promoting automatic voter registration can come with political costs

The Biden executive order’s call for more action has drawn criticism from Republicans, including on the House Committee on Oversight and Reform, which has been pushing federal agencies to release more information about how they are promoting voter registration.

In Pennsylvania, a group of more than two dozen Republican state lawmakers represented by the America First Policy Institute — which is run by former Trump administration officials — recently filed a federal lawsuit that claims Biden’s executive order is unconstitutional.

That kind of opposition could force decisionmakers into making political calculations before advancing automatic voter registration efforts, says Michener, the Cornell professor.

“This is the kind of thing that could very easily be viewed as a partisan move and not a move that’s about supporting democracy,” Michener says. “It’s a little tricky if you’re a Democrat and you want to do it really because you think it’s good for democracy and not because you think it’s good for your party. How do you proceed in a way that is supportive but not necessarily going to kick up partisan dust that is only going to make it harder to make progress?”

Another potential political hurdle is the uncertainty that comes with automatically registering eligible voters who may then make election outcomes less predictable.

“If you don’t want increased political participation by low-income people because you don’t know what that might mean for the votes that you get or the votes that members of your party get, you really may not be interested in this,” Michener says.

Edited by Benjamin Swasey