“Maybe I should run, I’m only 21, I don’t even know who I want to become,” sings the woman with 4 million TikTok followers who sounds like she’s from another era entirely.

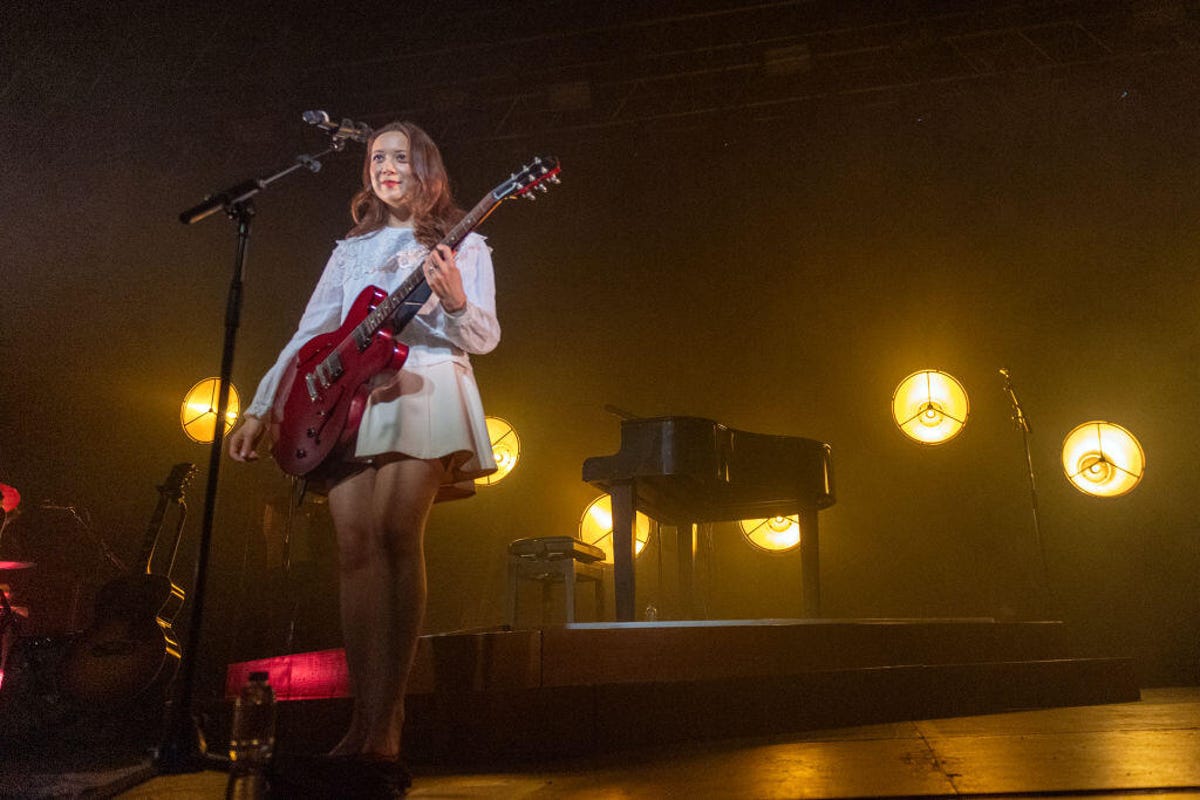

She’s on stage in an industrial warehouse in Glasgow, Scotland, on a Monday night in early 2024, but it could as easily be a 1930s jazz club. A double bass player and drummer are riffing in the shadows, while in the warm haze of diffused lights, the singer’s elegant and melancholic voice washes over a crowd of girls with bows in their hair.

This is exactly the kind of show I frequently attend – a female singer-songwriter, an audience of enraptured women. But Laufey (pronounced lay-vay) is a very different type of musician, a kind I’ve never seen before and might not have if it weren’t for TikTok.

Now 24, the Icelandic-Chinese composer/singer/songwriter/multi-instrumentalist has said in interviews that she’s as much influenced by Chopin, Liszt, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald as she is Taylor Swift. Her musical career has taken her from performing as a soloist on cello with the Iceland Symphony Orchestra at 15 through to graduating Berklee College of Music in Boston, to now, when you have to beg, borrow or steal if you hope to score a ticket to her sold-out tour (I only did the first two).

By the time I see Laufey, her elegant, velveteen voice warming up that drafty warehouse, I’ve been on an entire sonic journey on TikTok and across the internet, discovering artists I never knew existed and signing on as a member of the Laufey fanclub (or Lauvers, as we’re know).

The young TikTok star is fresh from performing at the Grammys a week prior – but the audience here, on the second night of her first European tour, lives for the Laufey they see on the small screen in their pockets, rather than the one on a primetime broadcast. She might be a classically trained musician known to the Recording Academy for her jazz-inflected sound, but to her fans, she’s Laufey who runs a bookclub on Instagram and Laufey who participates in the same TikTok trends they do. They stood outside in wintry rain and hail to finally see her up close. On stage, Laufey praises the crowd’s resilience: “I was getting DMs from you guys, saying ‘Let me in.'”

As with many of her Gen Z contemporaries, Laufey’s success has come at least in part by way of TikTok. The China-owned platform, which has over 1 billion users worldwide and almost 170 million active users in the US alone, is arguably the most influential destination right now for rising musical superstars to get discovered (the others being platforms like Spotify and Soundcloud) by labels and by fans.

Laufey

“That’s the beauty of the TikTok experience – that you can be an emerging artist who comes up there,” says Lisa Skeppner, music partnerships manager at TikTok. “You post five videos and your sixth really connects and it goes viral.”

For us, the listeners, it’s a chance to have our minds opened to music that might never have otherwise come our way and an opportunity to appreciate the creativity, skill and expertise that goes into making that music.

TikTok has long been understood as a viral hitmaker, but artists, producers and tastemakers, often armed with little more than a smartphone, a ring light and a mic, have also turned it into a hub of creativity. It’s become a venue for collaboration with their fans and other artists. It’s a sanctuary where diverse talent can showcase everything they’re capable of on their terms, making connections and building communities from the relative safety of their bedrooms. For some, it’s paved the way to life-changing record deals, while for others, TikTok is a way to bypass industry gatekeepers who don’t believe in them or have held them back.

There’s room for everyone to thrive. Whether you play the church organ or make beats from household objects, it’s a place to find inspiration, collaborators and audiences. If you’re really fortunate, TikTok can catapult you onto the Coachella lineup, Grammy stage or Barbie soundtrack – or, if you’re Ice Spice, all three.

Success such as this is rare, but the power of digital platforms is that they create space for musicians to succeed outside of the industry’s constraints – which, right now, include keeping artists’ music off TikTok altogether if you’re Universal Music Group, after the two sides failed to agree on the terms for a contract renewal: largely over matters of artist compensation, but also AI-generated music and online safety. That rupture, which hit at the end of January, just days before the Grammys ceremony, has cast a cloud over the TikTok music scene, especially for fans who make their own dance videos, and it’s unclear how the clash will play out.

What is clear is that who has creative control, who gets to be tastemaker and who gets to be heard is no longer simply in the hands of record company executives. Just as streaming services have put a truly incomprehensible number of songs at our fingertips, TikTok has shown there is infinitely expansive room available for people to make music and connect with audiences.

You may well have preconceived notions about the music that Gen Z (roughly, those now between the ages of 12 and 27) is making and listening to – even as a millennial TikTok user, I know I did. But the truth I’ve discovered is that the Gen Z music scene is thrillingly diverse, and in writing this piece I’ve been transported around the world before landing in a venue just down the road, watching a woman play a cello as a crowd of teenage girls (and some in their twenties and thirties) pointed their cellphones back at her.

Our brave, new, genre-fluid world

The question “Is Laufey jazz?” has been hotly debated across Reddit and YouTube, and was reignited following her Grammy nomination last year. She scored her award win at the 2024 Grammys event in the category of traditional pop album, though her music is most frequently compared to jazz standards from the middle of the 20th century.

A puzzler, to be sure, but one that rather misses the point of Laufey, and of Gen Z music trends altogether. Laufey is at the same time a pop princess with an old soul, a young ambassador for a venerable musical genre and a classical virtuoso with a mainstream fanbase. Speaking on the Glasgow stage about her shared love of classical, jazz and pop, Laufey says that with her Grammy-winning album Bewitched she “just wanted to find a way to mix them all.”

Laufey at the 2024 Grammys ceremony, holding her award for best traditional pop vocal album for Bewitched.

The idea of tightly defined musical genres as boxes into which musicians are sorted has been coming undone for some time, but Gen Z artists and listeners truly seem to have little time for the concept.

The most obvious example is Lil Nas X, who did the unthinkable in 2019 occupying a record 19 weeks at the top of the Billboard charts with his country-rap song Old Town Road. The runaway success of the song, which went viral on TikTok, was a clear indicator to the music industry that genre, as they knew it, was dead.

As is clear with Laufey’s traditional pop Grammy win, the old pillars of the music industry haven’t yet totally figured out their place in this new genre-fluid world. Streaming services, which possess all the granular data about users’ listening habits to see the bigger, more nuanced picture, are doing a better, if not perfect, job of embracing cross-genre listening patterns.

Ari Elkins

Spotify is increasingly introducing playlists based on vibes rather than genres, some (look up the enigmatically named “Pollen” and “Lorem”) tied together with a vague genre-fluid theme. What we once understood as “genre” is now “feeling,” according to playlist curator Ari Elkins.

The 23-year-old had a summer A&R internship with Warner lined up when the pandemic hit. It clearly would have been a good fit. As a TikTok creator, Elkins has found his niche in helping people discover new songs and artists and clearly has a knack for trendspotting in the oversaturated world of music streaming, and last year launched his own label, Blue Suede Records.

Along with 2.2 million TikTok followers, he has over 200,000 followers on Spotify, where he makes playlists with titles such as Late Night Drive, Saturday At Noon and Let’s Go On An Adventure.

“People want music that makes them feel a certain way, and that’s the real genre,” he says. “Artists are doing a great job as well as in being genre-bending themselves.”

One of the biggest artists to have found fame off the back of TikTok is 22-year-old PinkPantheress. The British star went from making music in her bedroom to having a song on the Barbie soundtrack and landing a BillBoard 100 spot last year thanks to her collaboration with TikTok sensation Ice Spice.

But critics and fans alike have struggled to concretely link her sound to a specific genre. Instead, it’s been described variously as bedroom pop, drum and bass, alt pop, dance, garage, jungle and breakbeat. Her collaborations with other artists have seen her stray further still across an entire spectrum of niche subgenres.

What defines her sound more readily than any of these descriptors is her tendency to sample tracks widely, from Spandau Ballet to Linkin Park. Layered with her sweetly distorted vocals, this is the essence of her unique sound that reaches both backward and forward in time.

In generations past there was often embarrassment attached to listening to anything your parents might have been into the first time around, but many Gen Z music fans seem to be liberated from this stigma. Their digital nativism means they’ve grown up with the entirety of the Spotify or Apple Music streaming catalog at their fingertips, and they roam freely and widely across decades and genres in search of music that resonates with them.

On TikTok, Skeppner has worked both with new Gen Z artists and with icons such as the Rolling Stones and Kylie Minogue, and has witnessed artists of all ages and specialties resonate with the platform’s audiences. “What’s so nice with TikTok is that it really is a mix and boundaryless, I would say in terms of both genres, but also ages and types of music,” she says.

Responding to this, Gen Z artists are fearless in their willingness to make the old new again – whether that be PinkPantheress producing songs inspired by Eminem and Craig David, Laufey combining ’40s jazz standards with contemporary heartbreak or Olivia Rodrigo layering her own teen rage and angst on top of Paramore’s pop punk anthem Misery Business.

Gen Z’s genre-fluid listening tastes mean they’re also embracing music from artists from far outside their own cultures. K-Pop and Afrobeats are two of the best-known non-Western genres to make serious waves in the US and other English-speaking countries, but even smaller music movements are finding audiences among new fans who without the internet might never have known of their existence.

According to Spotify’s 2023 Culture Next report, which provides insight into its Gen Z users’ listening habits, “the viral nature of digital platforms is also amplifying once-niche, hyper-local sounds,” such as sierreño, banda and corridos from Northern Mexico, and amapiano, kwaito and gqom from South Africa.

Once upon a time, if you wanted a career as a musician, you first needed to break through in your home country – or even state or city – before growing a foreign fanbase on top of your local success. With platforms like TikTok, that’s no longer the case. For young artists, this means sometimes their fans can be concentrated far away from their home market.

The TikTok effect

When British artist Chinchilla released her viral hit Little Girl Gone on TikTok in 2023, she was surprised to find that it was resonating more strongly in the US than the UK. People assumed she was American, and she had labels reaching out to her from all over the world, she tells me over Zoom from her bedroom in London.

“You’re able to reach people on the complete opposite side of the world without even meaning to,” she says. “It’s a good little joke from fate.”

Chinchilla

The song got over 1 billion views on TikTok and made Chinchilla the first female soloist in the six-year history of the Billboard Emerging Artists chart to debut at No. 1. When I ask why she thinks Little Girl Gone – a high-impact feminist rage banger – resonated so widely, she can’t pinpoint the reasons. “If I knew the recipe, I’d do it every time,” she says.

Chinchilla herself was “obsessed” with the song, she says, so much that she would sing it to herself as she walked down the street. She was less thrilled when, on a night out in London, one music industry man accused her of writing the song for the TikTok algorithm. “Fuck that,” she says. “I would never do that – write a song for the purpose of it blowing up on a platform.”

Writing songs with the intention of capturing the imagination of TikTok does happen, but it’s usually the idea of a record company executive rather than a young independent artist. Labels are known to pressure established and burgeoning stars alike to produce TikTok viral hits – how else to explain Justin Bieber’s thirsty campaign around the release of his 2020 song Yummy. At the same time, they lurk like vultures, scooping up breakthrough TikTok artists with viral songs and handing them record deals.

The relationship between labels and tech companies has always been fractious (Spotify and YouTube both have priors), and so continues the trend with TikTok. Labels want to harness the potential of popular new platforms to promote their artists and scout for new talent, but at the same time want a share of the tech companies’ profits.

This can lead to conflict, such as the ongoing spat between Universal and TikTok, which saw the record label pull all of its music (including key artists such as Taylor Swift, Ariana Grande and Olivia Rodrigo) from the platform. As music by Universal artists is often used to soundtrack videos, it’s now easy to stumble across people dancing and lip-syncing to nothing but silence.

“Ultimately TikTok is trying to build a music-based business, without paying fair value for the music,” said UMG in a blog post. In response, TikTok said Universal had “chosen to walk away from the powerful support of a platform with well over a billion users that serves as a free promotional and discovery vehicle for their talent.”

‘They want to get heard’

Meanwhile, the Gen Z musicians on TikTok continue to create content and put out music on the platform, often with little thought to the legal or financial aspects of the business. “A lot of young artists, their first priority is they want to get heard,” says Stuart Dredge, head of insight at music industry analysis firm Music Ally.

And if you’re sitting at home making music in your suburban bedroom, TikTok is the best, and perhaps only way for you to bypass the traditional industry gatekeepers and find an audience that otherwise might never encounter your work.

“It shocked me how much sharing online has affected my professional life,” says producer So Wylie, who has built up a following on TikTok for, among other things, making beats out of bird calls that enchanted the online birdwatching community. She’s subsequently produced for recording artists, film and TV, podcasts and brands. The combination of sharing her original music and her personality means that TikTok acts as “a sort of casual public resume,” while allowing professional connections to glean an understanding of her work style and general vibe.

For PinkPantheress, TikTok was a direct on-ramp to a musical career that otherwise would likely have taken much longer. “I don’t like long processes,” she told the Guardian last November. “There needed to be some quick, quick way for me to do this.”

TikTok can provide artists with a way out of a tricky spot even if they do already have industry backing. After extricating herself from her record deal with Polydor in 2021, the artist Raye said the company had been holding her back from releasing her debut album for years. In 2022, she released her song Escapism, and by the end of the year it had gone viral on TikTok, scoring her first No. 1 single in the UK and first entry into the Billboard chart.

There are echoes of Raye’s story in Chinchilla’s own journey to musical stardom. Shortly before releasing Little Girl Gone, she too parted ways with a label. It goes to show that a record deal is no longer the golden ticket it once was, and that sometimes you may even be better off going it alone. “The hardest thing for a new artist to get is exposure,” says Chinchilla. TikTok is the best way of cutting out “the middleman of the music industry” and finding your fan base, she adds.

There are a lot of good reasons to be with a record label (promo, distribution, credibility, to name a few), says Dredge, but independence can offer an element of safety and control. “There’s kind of a route now where you could break through on TikTok and stay independent,” he says. “Young artists now are very aware of the options.”

Observing the stratospheric ascent of Little Girl Gone, it was TikTok in the end that swooped in and gave Chinchilla a helping hand to capitalize on the song’s success. Tiktok’s music team was aware she was doing it all by herself, she says, and sent opportunities her way – including inviting her to join its newly launched Elevate program.

The purpose of Elevate, TikTok said when it announced the program last summer, is to identify, amplify and celebrate emerging artists. Chinchilla is one of six artists in the inaugural class. Through Elevate, she recorded a performance of her song Cut You Off at the Alexandra Palace ice rink in London, where she skated competitively growing up, which she describes as “an emotional, amazing, full-circle moment.”

The power of music fans on TikTok

TikTok might be where young artists are finding their audiences, but for as long as the internet has existed, exciting musical talent has always found a way to make digital platforms work for them. Many of today’s biggest names, including Taylor Swift, Adele and Arctic Monkeys, used MySpace to share their music and connect with their very first fans. Justin Bieber made his name on YouTube, and Shawn Mendes was one of the breakout artists to emerge from TikTok’s ill-fated predecessor, Vine.

It’s hard not to compare these new fan communities to the days when Swift used to hang out on Tumblr and knew many of her fans by name. What makes TikTok different, says Dredge, is that from the start it was more about content created by fans than by artists themselves. For a long time, TikTok was known almost exclusively for its lip-syncing and dancing videos – proof that it’s always been a music-first platform. From here, it’s blossomed into a hub of creativity where co-creation between artists or fans and artists is the norm.

So Wylie

“A lot of my audience are talented musicians or music lovers – I respect them and I am actively trying to impress them,” says Wylie. “This pushes me to try new production techniques in the hopes of inspiring people to make their own art.”

TikTok has introduced features that help fuel this co-creation process – and has more in the works. “On TikTok, the little piece of magic is the duet feature, because that really allows for artists or fans to be kind of virtually close up,” says Skeppner. The tool lets anyone on TikTok repost other people’s videos with their own video side by side, adding their voice or instrumentation to an original track.

Many of the viral songs you might have heard on or from TikTok are also the sped-up or slowed-down versions of what the artist originally put out. This trend has become so popular that now labels are pushing out these versions of their artists’ songs, says Skeppner, but that’s not how it started.

“Originally it was fans just remixing and changing and amending,” she says. It can be a sensitive matter to artists, she adds, but can also give a song a second life or an entirely different feel. Raye’s hit Escapism is a classic example of a track that scored its viral moment thanks to fan tinkering. Says Skeppner: “It was her fans really, and her leaning into it.”

A place to experiment

Many TikTok artists and producers use the platform not only as a way to promo new music, but to experiment and crowdsource opinions on new material. Stars including Charlie Puth and Tom Odell have teased upcoming releases there, and sometimes the clamor over a snippet posted to TikTok has moved up the release schedule for songs, says Skeppner.

From an artist’s perspective, the feedback from TikTok can play a key role in the creative process. “TikTok specifically has a low-key energy to it that allows me to be playful with the types of music I post,” says Wylie.

It’s easy for musicians to get caught up in the idea of making everything perfect before putting it out into the world, she adds, but on TikTok she can post snippets without the pressure of an official release date. “Though it might seem counterintuitive, I actually find the fickleness of the algorithm helpful in that particular respect,” she says. “I never expect anything from it, so that makes it easier to just put stuff out there.”

During the pandemic singer/songwriter/producer Ellie Dixon really went all in on music – and on TikTok. She was making beats from household objects, creating harmonies to layer on top of other people’s music, writing her own verses to popular songs and slotting them in using her production skills.

Ellie Dixon

“I did it all day, every single day,” she says. “I didn’t take a break.” As her fan base grew, she started collaborating with other creators, getting into writing sessions over Zoom and producing for other artists. Everyone being stuck at home at the same time provided a unique opportunity for collaboration – including being recognized by much bigger names in the industry.

“I was quite lucky to have hit the online world at that time because bigger artists didn’t have anything else to do than interact with their fans,” says Dixon. The band Glass Animals reposted a cover of one of her songs, and as her network and community expanded, the industry began paying attention. In 2022 she signed to Decca Records, part of Universal. (Her workaround to the Universal-TikTok standoff? Play her music on the recorder.)

“Now I’ve reached a point where I’m still making music in my bedroom, but a major label is willing to release what I’m making, which, genuinely, if you told 15-year-old Ellie that, she wouldn’t believe you.”

Not all artists have embraced TikTok with such enthusiasm. Both new and established acts have complained about the pressure from labels to endlessly self promote on TikTok.

Singer Ricky Montgomery, who scored a record deal off the back of a viral TikTok hit in 2021, posted a video to the platform in December lamenting that making content was taking valuable time away from making new music. “Even when you get here, to a label, it doesn’t end,” he says. “In fact, it might get more important to continue posting your stuff.”

Patching the discoverability gap

Not every story about TikTok can end with a viral hit and a record deal. No matter how much talent and tenacity you might bring to the table, in a world where everything is algorithmically determined, there are no guarantees.

Even artists who experience their song blowing up on TikTok can struggle to catch the wave. Maybe their music is the soundtrack to a widespread trend, but that doesn’t necessarily mean people will know their name, face or backstory.

The same can be true for streaming services. How many artists have you learned the name of based on the algorithmically made playlists that have been generated for you? I know I can’t be the only one guilty of listening passively rather than actively to my Spotify Discover Weekly playlist.

In an age where 120,000 new songs are uploaded to streaming services every day, music journalism is struggling to survive and AI is increasingly doing the heavy listening when it comes to determining what we hear, forming new and deep connections between artists and fans isn’t always easy. The result is that both lose out.

Tech companies are trying to help connect the dots – TikTok by creating an emerging artists hub and providing links so people can easily add songs to streaming service playlists; streaming services by employing human editors to act as curators.

Elkins, whose entire internet presence is based on recommending music to his followers, believes music fans still appreciate the human touch of someone they trust telling them what to listen to – like a friend burning you a mixtape or CD. Every week now, labels send him new music to listen to so that he can encourage his own TikTok community (he tells me he largely shares the same taste as 18- to 23-year-old women) to get on board.

TikTok might be algorithmically driven, but creators like Elkins are finding ways to harness the platform to solve the discoverability problem. Likewise, for Gen Z artists who have grown up making content, social media can be an invaluable tool in telling their stories to fans to cement that deeper connection.

TikTok is especially handy for this, as it allows them to speak directly to the camera, to jump on the same popular trends as their fans and show different sides of their personality. On many Gen Z artists’ TikTok channels you’ll find videos of them dressed to the nines and performing on stage, shoulder to shoulder with stripped-back videos of them, makeup free, in their bedrooms.

As a music lover, discovering your new favorite artist through their social profiles provides a portal into their creative vision. “You can’t measure the power of these platforms in building those bonds,” says Dredge. Different platforms can serve different purposes, and artists often have their own preferences or opinions about where is most or least toxic. As well as TikTok, Dixon likes Instagram, but not the comment section. “I live in my DMs,” she says.

One of the reasons tech platforms end up becoming such music-centric communities is that many Gen Z artists are already hanging out on them as users long before finding their own audience, says Dredge. “When you have a whole big community of creativity, some of those people are going to be musicians, and when they emerge from that pool, they’re just native to it.”

Smart tech companies and labels are hiring Gen Z folks, he adds, who are digital natives and therefore have an in-built ability to navigate the landscape. Folks like Skeppner, for example, who over the past four years has helped labels develop TikTok launch strategies for acts including ABBA, Lady Gaga and Nile Rodgers.

The tech world never stands still for long, and just as the labels have wrapped their heads around TikTok, Gen Z artists are already starting to connect with fans in new digital venues like Roblox (where you can buy a Lil Nas X cowboy hat) and Discord. Dixon is a big fan of Discord and regularly has calls there with her fans.

“We’ve all got the same kind of interests and music that we love,” she says. “Every time I forget that I’m with fans and not just mates.”

From your bedroom, to the world

Just as Gen Z artists aren’t the first to break through on digital platforms, bedroom pop (the genre) and bedroom producers (the people) are concepts they’ve grown up with rather than invented. Dixon says that as a teenager she was inspired by watching bedroom producers like Dodie on YouTube.

It’s perhaps not a coincidence that many of the young artists and producers whose careers are blowing up via TikTok and their bedroom studios are women or non-binary. The music industry doesn’t always save them a seat at the table, and when it does, it doesn’t always have their best interests at heart.

Two weeks ago, a UK parliamentary committee released a report stating that misogyny was “endemic” in the music industry and that an investigation had revealed sexual harassment and abuse to be common. Many incidents go unreported, but Gen Z artists breaking through have grown up with an awareness of the issue thanks to the bravery of stars like Kesha, Raye and Taylor Swift talking publicly about their experiences of assault.

One of the reasons Dixon says she’s continued making music in her bedroom is because it provides her with a controlled environment. “The accessibility of tech has made it so that you don’t have to go into spaces that you don’t see yourself in to make music,” she says. “You’re also not at the mercy of whatever producer is making your music for you.”

Not only does TikTok allow young artists and producers to determine the environment where they make music, it also gives them more agency over their own narrative. It can feel “liberating,” says Chinchilla, to use TikTok to show people that their assumptions about you are wrong – for example by revealing production breakdowns that prove you’re actually making the music yourself. “Sometimes people need to see things to believe it,” she says.

Female artists who are now beginning to dominate the formerly male-dominated electronic music space have credited TikTok with breaking down barriers. When you combine access to digital platforms with microphones, cameras, beat pads and a laptop with recording software, they have everything they need to make their own music – and to show how they’re doing it.

Social media has made it easier for Wylie to find support among other women and non-binary producers, and allows her to follow their careers. She’d like to see that reflected in the mainstream music industry. “What we need next are avenues for women to thrive in audio engineering and production behind the scenes, without feeling like they have to be visible,” she says.

Access to education and tools are crucial in paving the way for more girls to have the confidence to thrive in production spaces. Wylie, who struggled for years with hiding any gaps in her skills for fear of proving people’s assumptions about her, encourages young people lacking in confidence to ask questions, even if they think they’re stupid. “The other thing that has helped me is to try to be extremely resourceful,” she says. “I’m that girl who reads the manual.”

Dredge believes having confidence in their hard tech skills has the potential to give young artists more agency over how and where they work, as well as who they work with. “Some of these problems… that have been barriers to older artists, I hope they’re gonna get smashed down by this generation of artists,” he says. They’re more likely to ask, “why would I not produce myself? Why would I not have control of what happens on stage?”

Laufey on stage in Glasgow, Scotland, on Feb. 12.

Going live

Making music from the safety of your bedroom is all well and good, but at some point, especially if you score a record deal, you’re probably going to have to get up on stage in front of a live audience.

The music industry still relies on ticket sales to make money (PWC estimated the global live music ticket market was worth $23 billion in 2023), and even TikTok is getting in on the action. Late last year it announced a partnership with Ticketmaster that allows artists to sell tickets to their shows directly through the app. Last December, it even ran its own festival, In The Mix, in Mesa, Arizona, which featured artists from its Elevate program and established stars including Niall Horan and Cardi B.

For some young artists, the jump to the stage comes naturally, but for others, more used to performing to cameras instead of crowds, it’s not always an easy transition. But it can also be remarkable to see how quickly some young artists adapt to the demands of touring life. When 19-year-old artist Gayle, who went viral on TikTok in 2021 with her hit ABCDEFU, canceled her “Avoiding College” tour in 2022, she gave the reason as: “I’m learning how to be an adult.” By the following summer, she was supporting Taylor Swift and Pink on their stadium tours.

Dixon has undergone a similar change of heart about playing live – even though it’s been “a trial by fire” to get there. Her first gig after COVID was on the BBC Introducing stage at the Latitude Festival in Suffolk, England. The day started with a panic attack in the tent, but once she was on stage and could see people wearing her merch and singing her words back to her, it all changed. Now, having toured extensively – both as support to the band Pentatonix and as a headliner – she loves it.

Learning to talk to the audience was a challenge, but now it’s her favorite bit. “At my last tour people were saying that it felt more like a standup show.” She even brings the collaborative spirit of her TikTok persona on stage with her – writing silly songs with her audience (and posting them online later).

There’s no reason that TikTok stars hitting the stage need to follow conventional gig parameters, says Dredge. Mixing in traditional musical performances with what they’re known for on the internet, plus some audience interaction that mimics the comment section, may even be a better fit for meeting fans’ expectations.

Laufey, known for being a serious virtuoso and for wistful, yearning lyrics, leans into this by revealing herself with sarcastic quips between songs. Lit by a single spot during her Glasgow show, she is at times an ethereal princess playing the piano or cello. The next moment, she’s sassily impish, side-eying Valentine’s Day and bopping around coquettishly while holding up bunny ears behind her twin sister Junia, who’s on stage with a violin to accompany Laufey on her biggest hit, From The Start.

“Did anyone here not know I was a twin?” she jokes. There’s laughter – everyone here does know that. Just as they know to anticipate the song Beautiful Stranger when she mentions living in London, or Falling Behind when she talks about moving to LA. The mythology is strong here, woven not just through her music, but by providing her fans a portal into “Laufey Land” on social media.

In her encore, a rendition of Letter to My 13 Year Old Self, she changes the lyrics to reference her Grammy win. “One day, you’ll be up on stage/Little girls will scream your name,” she purrs into the microphone, and they’re ready for her – the girls with ribbons in their hair who watched her TikTok videos and queued in the rain to yell her name right back at her.

Visual Designer | Zooey Liao

Video | Jessica Fiero, Chris Pavey

Senior Project Manager | Danielle Ramirez

Director of Content | Jonathan Skillings