Nobel peace prize honoree Malala Yousafzai is calling for an end to “gender apartheid.”

COVID is no longer a global health emergency but will the coming year see a “cholera comeback”?

And if you’re feeling a bit overwhelmed by election coverage here in the U.S. for the November event, keep in mind that 2024 is going to be a “mega-election year” on Earth — more elections than ever in the history of elections, some election watchers say.

These are a few of the buzzwords in the world of global health and development and humanitarian causes that we cover for Goats and Soda. We talked to specialists in these fields to create a list of terms that we’ll likely be hearing in the year ahead — both new coinages as well as tried-and-true buzzwords that still are top of mind.

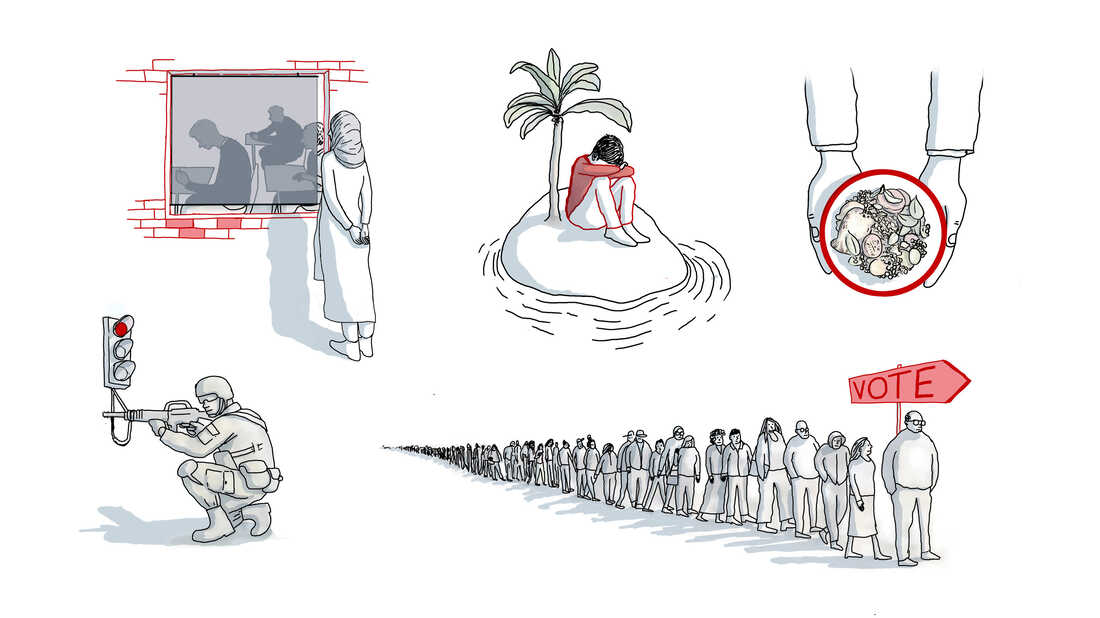

Gender apartheid

In a December speech, Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai drew attention to the persecution of women and girls by the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. Speaking in South Africa, Yousafzai pointed out how leaders like Nelson Mandela confronted and criminalized racial apartheid at the international level, “but gender apartheid has not been explicitly codified yet. That is why I call on every government, in every country, to make gender apartheid a crime against humanity.”

The Pakistani activist, who as a teenager was shot in the head by Taliban gunmen for advocating girls’ education, was echoing long-held concerns over the Taliban’s countless edicts to remove women from public life since the militant group seized power in Afghanistan. It remains the only country in the world that bans girls from school beyond sixth grade. In October, a joint statement by scholars and civil society organizations urged governments to codify the crime of gender apartheid through the United Nations, saying “the international community must properly recognize the harms of a legally enshrined system in which women are treated as second‑class citizens.”

Secretary General Antonio Guterres said last year, referring to the situation in Afghanistan: “Unprecedented, systemic attacks on women’s and girls’ rights and the flouting of international obligations are creating gender-based apartheid.”

With activists ramping up their campaigning, will 2024 see gender apartheid codified under international law?

Funding crisis

Amid the world’s conflicts and climate emergencies, the humanitarian sector is facing not just a funding gap — insufficient money to meet goals — but what some are calling “a funding crisis.” In its end-of-year Global Humanitarian Overview, the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) painted a bleak picture, saying lives were at risk because of “the worst shortfall in funding for years.”

“In 2023, we received just over one-third of the $57 billion required,” OCHA head Martin Griffiths wrote in a statement. “As a result, the target for 2024 has had to be scaled back to helping 181 million people, rather than the 245 million originally targeted.” Funding shortfalls are the norm in international aid, but Griffiths said this was the first time since 2010 that year-over-year funding decreased.

That point is echoed by Mark Smith, vice president, Humanitarian and Emergency Affairs for the charity World Vision: “There’s always been a gap between what’s available in money and what’s needed but this year my colleagues and I tend to say ‘humanitarian funding crisis.’ What’s different about this year is the needs have continued to increase but we may see funding definitely decrease. We haven’t seen that in the last 15 years.”

The statistics from OCHA establish the scope of what’s needed: One in ever’ five children lives in, or has fled from a conflict zone, one in 73 people globally have been forcibly displaced and 258 million are facing acute hunger. Noted Griffiths: “If we cannot provide more help in 2024, people will pay for it with their lives.”

Cholera comeback

The World Health Organization (WHO) was established in the wake of cholera epidemics sweeping Europe in the 19th century. Cholera, a bacterial infection that causes an acute diarrheal illness, spreads when people consume contaminated food or water. Without treatment, it can kill in hours. And now it’s on the rise again.

In 2023 there were over 5,000 cholera deaths, more than double the previous year. The new year begins with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting 27 countries with areas of active cholera transmission, four more than the previous year. In the last two years Lebanon has reported their first cases in decades and Malawi has reported its deadliest outbreak in history.

Access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene are key to preventing the spread, but post-pandemic poverty as well as displacement by surging conflicts, are major disrupters, say health specialists. Climate change also plays a role, with high temperatures and heavy rainfall making it harder to access clean water.

WHO is calling for strong public health surveillance systems to identify cases and investing in water sanitation and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure to prevent further outbreaks. Meanwhile, Gavi, the international vaccine alliance, has warned that shortages of oral vaccines will continue into 2025 due to increasing demand and falling production.

Humanitarian pause

The end of 2023 was marked by roiling conflict in Sudan, grinding war in Ukraine and a widening conflict in the Middle East. How to stop the fighting, and even the words used to describe such a break in hostilities, will be big parts of the global conversation in 2024 — as well the phrase “humanitarian pause.”

Following the October 7 Hamas attack on Israel and subsequent Israeli siege of Gaza, a six-day “humanitarian pause” in November allowed the exchange of hostages and prisoners as well as food and fuel.

According to the U.N., a humanitarian pause is usually time-limited and confined to a particular geographic area, while a ceasefire is intended for warring parties to conduct dialogue for a permanent resolution.

A report from the think tank Chatham House points out that while none of the terms is defined under international law, a humanitarian pause can allow specific measures such as “evacuation of the wounded and sick, or facilitating the rapid and unimpeded passage of humanitarian relief,” which are required by international law.

On December 1, fighting resumed in Gaza. Oxfam said that though the brief respite was welcome, “this was never going to be enough considering that 1.8 million people – or 80% of Gaza’s entire population – has already been displaced.” Like numerous other aid agencies, it has insisted upon a complete “ceasefire.”

And of course “ceasefire” is another word in frequent usage. Beyond Gaza, ceasefires have been floated cautiously in some of the world’s long-running conflicts. This week the United States called for one in Sudan to end the nine-month hostilities between government and paramilitary forces. Before this year’s attacks on the Red Sea, the U.N. was welcoming moves by the Houthis and the Saudi-backed government in Yemen to end fighting. Last week China claimed to have brokered a ceasefire between Myanmar’s military junta and ethnic minority guerilla groups. Amid such bloodshed, could 2024 hold out hope for some outbreaks of permanent peace in unexpected places?

Food insecurity

A buzzword for far too many years, “food insecurity” is likely to be trending again this year.

The U.N. goal of “creating a world free from hunger” by 2030 increasingly looks like a pipe dream. Recent data revealed that in 2022 nearly three quarters of a billion people faced chronic hunger – the long-term inability to meet dietary energy needs. 2024 could be a major test of the international community’s commitment to “zero hunger.”

Ongoing supply chain disruptions from the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, as well as current attacks in the Red Sea, could drive up food and fertilizer prices into 2024. The extreme weather events caused by El Nino will also have an impact well into this year.

An October 2023 report by World Food Programme (WFP) and UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) predicts that acute food insecurity is likely to worsen in 18 hunger hotspots in early 2024. At the highest risk from starvation are people in Burkina Faso, Mali, the Palestinian territories, South Sudan and Sudan.

The WFP warns that the funding crisis mentioned above could push an additional 24 million people to the brink of starvation over the next year. In 2024, expect increasing calls for more investment in innovative farming methods like drought-resilient crops and early warning technology for emerging climate threats.

Climate mobility

Last year former U.S. Vice President Al Gore warned that without action, “there could be as many as one billion climate refugees crossing international borders in the next several decades.”

The term is controversial. Some, like the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) say it is confusing because “climate change is not itself grounds for refugee protection.” Instead, they suggest climate mobility as “perhaps the broadest umbrella term for the phenomenon, covering internal and international movement, whether forced or voluntary, temporary or permanent.”

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) points out that most climate mobility happens within borders, forecasting that that climate change will “cause the internal migration of up to 216 million persons by 2050.”

Even so, some countries are preparing to accommodate displaced people from countries most at risk. In a landmark pact in November, Australia agreed to extend residency permits to citizens of the South Pacific nation of Tuvalu due to the threat of rising seas.

IOM notes that while many people move because they have no choice, migration can also be a strategic adaptation to a changing climate. International bodies will have to reckon with both scenarios in 2024.

Small Island Developing States (SIDS)

In 2024, you may be hearing an acronym that sounds like another one you already know but has a very different meaning. In discussions about climate change, SIDS refers to Small Island Developing States — a collection of 39 countries, from the Caribbean to the South China Sea, that are most vulnerable to rising sea levels. Though small, they are becoming some of the loudest voices on the world stage calling for action on climate change.

Representatives of these island states were some of the most vociferous critics of last December’s COP28 climate summit in Dubai, with many saying they felt sidelined. It culminated with the concluding deal being rushed through with many of the key stakeholders absent. “We weren’t in the room when this decision was gaveled. And that is shocking to us,” the Marshall Islands’ climate envoy Tine Stege told reporters.

Even thought the deal will establish a loss and damage fund to help cover the devastating costs of climate change, many Small Island Developing States felt that the financing fell short and that there was no clear commitment to phase out fossil fuels.

To applause by delegates, Anne Rasmussen, Samoa’s lead negotiator, denounced the agreement as a “litany of loopholes” and said the deal would “potentially take us backward rather than forward.”

But looking to November’s COP29 global climate conference in Azerbaijan, Rasmussen noted that the agreement “was not the closing act but the opening scene of a reinvigorated fight.”

Mega-election year

2024 is set to be a historically consequential election year, with more than 60 countries representing around 4 billion people going to the polls. Some media outlets, like the Economist and the New Yorker, have declared it the biggest worldwide election year in history.

The results could fundamentally affect the rights of minorities, humanitarian aid funding, progress or backsliding on climate change and the risk of political violence. In his end-of-year letter, Bill Gates said that the 2024 elections will be “a turning point for both health and climate.” (Editor’s note: The Gates Foundation is a funder of NPR and Goats and Soda.)

Stability hangs in the balance in Mali, Chad and Burkina Faso, each recently rocked by coups and scheduled to hold votes this year. In India, the world’s largest democracy, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is vying for a third term amid accusations of an authoritarian streak and intolerance for religious minorities. European Parliament elections in June will be contested by a range of far-right populist parties with potentially far-reaching implications for migration policy and the war in Ukraine.

And on November 5 the United States – the world’s largest humanitarian aid donor – may once again see a battle between incumbent President Joe Biden and his predecessor Donald Trump, likely with funding for international development organizations and U.N. agencies in the balance.

Reader callout

Readers, if you have additional global buzzwords for 2024 you’d like to share, send the term and a brief explanation to goatsandsoda@npr.org with “buzzwords” in the subject line. We may include some of these submissions in a follow-up story.

Andrew Connelly is a British freelance journalist focusing on politics, migration and conflict.