tadamichi/iStock via Getty Images

By James J. Puplava

If you own a stock portfolio or are invested in the market, most likely you hold more than one company or have some degree of diversification. Or, as is very common today, you may own an Exchange-Traded Traded Fund (ETF) or several different ETFs that hold a large basket of companies. Well, looking back at last year, the best investment decision would have been to ignore diversification across various sectors, industries, or asset classes and simply follow that giant sucking sound of global capital rushing into seven stocks.

Yes, that’s right, I’m talking about the mega cap, big tech stocks we call the Magnificent 7 – Alphabet (GOOG), Amazon (AMZN), Apple (AAPL), Meta (META), Microsoft (MSFT), NVIDIA (NVDA), and Tesla (TSLA) – all of which are paving the way forward when it comes to robotics, automation, and artificial intelligence.

Throughout history, we’ve seen numerous instances where capital heavily concentrates on a single company or a small cluster of stocks, such as the Nifty 50 growth stocks in the 1970s or the tech sector in the late 1990s. Often, such herding is driven by a powerful narrative that captures the public imagination and investment capital of investors across the world at large. In these instances, large gains coupled with a good story dominate the headlines, and the consensus of the crowd becomes ever more convinced that the quickest and most effective way to get rich quick is through large bets or heavy positions in the magnificent or nifty stocks of the moment.

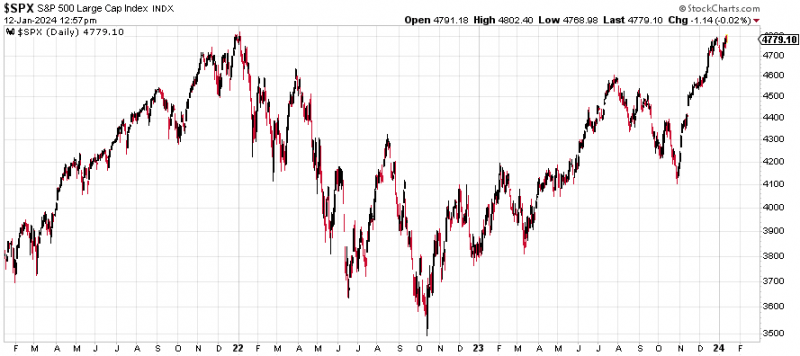

Given their steep valuations, there was a growing amount of concern and increasing discussion of tech entering another bubble-like phase as the Magnificent 7 stocks made a parabolic, vertical move after 2020. Market momentum then reversed in late 2021, and some of the big-cap tech names saw drawdowns of 50% or more over the course of 2022. Last year, they made another push higher, again accounting for the majority of market returns. The question we need to ask as investors is, how long will this last?

Stockcharts.com, Financial Sense Wealth Management. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

Currently, when we look at the S&P 500, the stock market is flirting with the all-time highs of last year as well as in late 2021, with a large focus on just how much the Federal Reserve will cut rates this year, helping to ease financial conditions with a view to borrowing costs across the interest rate curve. Given some initially stronger-than-expected economic numbers and end-of-year profit taking, the start of 2024 saw a slight wobble in sentiment and positioning, with a greater amount of uncertainty over the degree of Fed cuts expected this year in the context of a widely anticipated soft landing.

The current momentum in stock prices is based on a narrative that I believe will be tested this year. That dominant narrative is there will be no recession (that is, we’ll see a soft landing instead), and the Fed will pivot by lowering interest rates beginning in March. There is no definitive consensus on the number of rate cuts, as it varies by firm. Some like Goldman Sachs believe rate cuts will average between 25-50 basis points, others like UBS feel rate cuts will be in the 100-150 basis point range and few believe there will be no rate cuts at all.

For this Goldilocks scenario of no recession but lower inflation and lower interest rates to take place, which will likely have a meaningful impact on big tech’s record performance, I would like to share our view on the hurdles that will have to be overcome to make this happen. Like the Magnificent Seven, I present the Goldilocks Seven – 7 events that I believe will need to take place for the Goldilocks scenario to become reality in 2024.

The Goldilocks 7

- Long-term interest rates will need to come down and remain low well into 2025-2026. Right now, most corporations locked in their debt at low fixed rates by 2020. In 2025, 50% of that debt will be coming due and could put pressure on companies’ balance sheets if rates remain high. Large companies will have no difficulty. In addition to locking in low interest rates on their debt, they are also getting high Treasury yields on their cash. This is the best of both worlds: low fixed rate debt and high interest rates on cash. I don’t believe that will be the case heading into 2025.

- The second issue is smaller companies. Rising interest rates could become a major problem for smaller companies who finance at variable rates and if we get into a recessionary environment, they could be facing 7-9% interest rates on their debt. The key here is long-term rates need to fall significantly and remain there for the next several years.

- The next issue is the consumer, as two-thirds of GDP is driven by consumption. Consumers have been hit hard the last 24 months by high inflation on everything from food, utilities, gasoline prices to medical care. Most of the stimulus checks have been spent, and the surplus checks from the pandemic are gone. Consumers are now going into debt to pay essential living expenses. Consumer debt is now at a staggering $17.29 trillion, up $923 billion in 2023. The breakdown is shown below.

- Mortgages: $10.92 trillion (63.2% of total debt)

- Student loans: $1.74 trillion (10.1% of total debt)

- Auto loans: $1.51 trillion (8.7% of total debt)

- Credit Card debt: $1.08 trillion (6.3% of total debt)

- Other: $2.04 trillion ($11.7% of total debt)

For consumers to maintain spending, inflation will need to come down and wages will rise to keep the pace of spending supportive of a growing economy.

- With the yields on Treasuries rising, banks have experienced an outflow of $800 billion as consumers have taken their cash and invested in money market funds or Treasuries to get a higher yield. Banks base their lending on deposits. As deposits decline, there is less of a base that can be used for lending. According to the recent Federal Reserve Senior Loan Officer Survey on bank lending practices, overall banks have reported tightening standards for most loan categories, ranging from a tightening of 51% for residential mortgages to 40-43% on commercial and industrial loans. The reasons given for restricted lending range from rising interest rates, inflation, and economic uncertainty. Tightening lending leads to less economic activity.

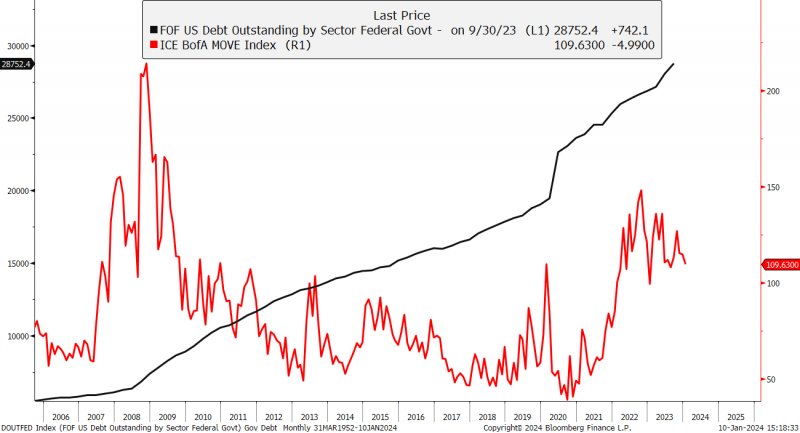

- Rising government debt and deficits with a higher debt/GDP ratio. For every dollar of economic spending, we are only seeing about $0.30-$0.40 cents of GDP growth. Government debt has risen close to 600% since 2000. It is now accelerating at an exponential rate. Even worse, the average interest rate on government debt has risen from a low of 2% to the current average of 2.97% and will rise even further as 1/3 of government debt comes due the next two years. Interest on the debt will become larger than the entire defense budget of $832 billion. This raises the issue of crowding out in the debt markets and is making our Treasury market more volatile, as reflected in the MOVE Index shown below alongside the graph of total government debt. It makes it more likely of an approaching debt crisis and Fed monetization of that debt, along with yield curve control.

Bloomberg, Financial Sense Wealth Management. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

- Factory utilization rates and pricing control need to come down. Currently, the factory utilization rate is 78.9%. This indicates that demand is strong enough for companies to be able to keep raising prices, which the Fed does not like. Coming out of the pandemic and lockdowns, we, as consumers, were buying lots of stuff as everything was shut down. Supply chain disruptions made goods more expensive and difficult to get. Even though these conditions have lessened, companies in many sectors of the economy are still flexing their pricing power, which is inflationary. I believe the Fed would want to see the utilization rate decline to the lower 70s to reduce pricing pressures.

- Labor market tightness is another factor, as there are approximately 2.5 million more jobs than those who are unemployed. Part of the labor tightness is due to government incentives for not working and baby boomers leaving the workforce for retirement. The Fed would like to see wage growth lessen, and the only way that is going to happen is if the unemployment rate begins to rise above the 4.1% level at a minimum.

The above factors will determine when and if the Fed lowers interest rates, despite Wall Street’s optimism it will happen as soon as March. Jay Powell is aware of making the same mistakes the Fed made during the 1970s, which saw a rise in inflation throughout the decade. In my opinion, the real inflation will return when oil prices start to trend higher as US shale oil production peaks this year or next and when the Fed is forced to start monetizing the debt, which I expect to see sometime between 2025-2028.

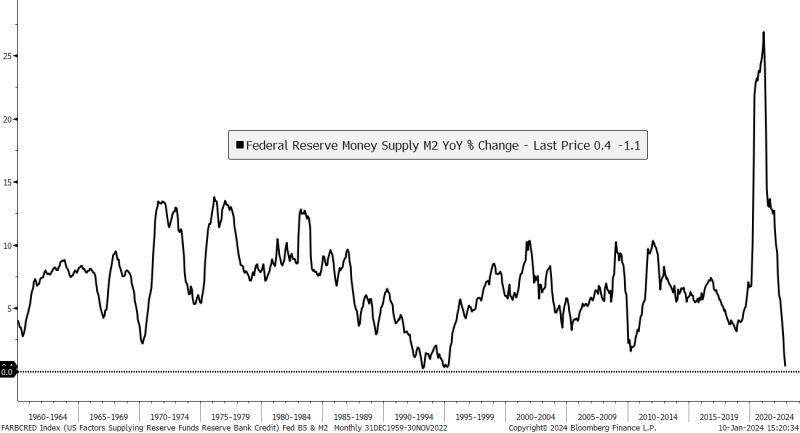

Last week, the market pulled back after the release of the Fed minutes from its December meeting. The minutes show the Fed is done raising rates for now but is in no hurry to lower them. Which raises the question of what happens next? Markets run on liquidity and, as shown below, the money supply is shrinking with FED quantitative tightening (QT) as well as bank credit tightening. So, two of the fuels for market expansion are declining.

Bloomberg, Financial Sense Wealth Management

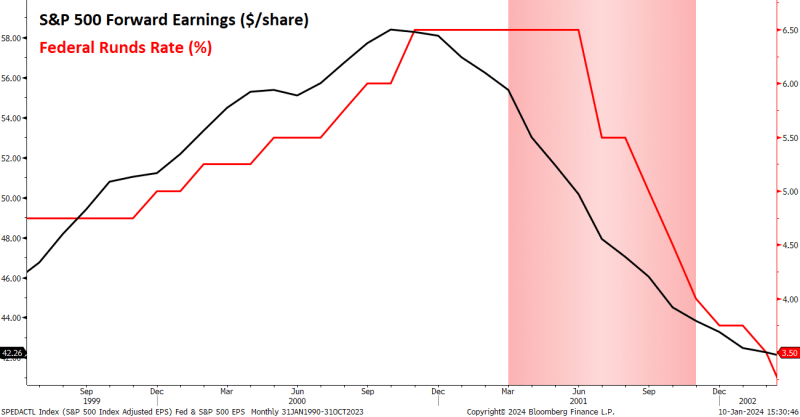

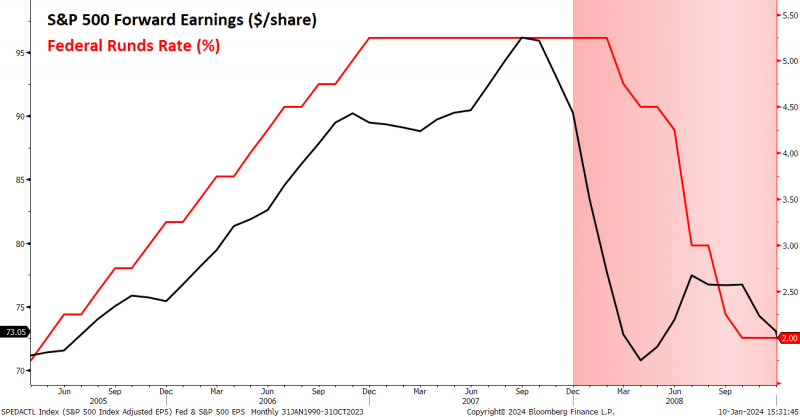

The next factor is corporate earnings, which will begin being reported this month. Earnings are looking good for Q4. However, corporate earnings are a lagging indicator and usually peak as the Fed goes on pause. When the Fed begins to lower rates, over 90% of the time it is when the economy is in a recession, and along with that recession is a steep drop in corporate earnings. You can see this below in the recessions of 2001 and 2008.

Bloomberg, Financial Sense Wealth Management. Past performance is no guarantee of future results

To summarize, we are not expecting a Goldilocks scenario to unfold this year. We expect greater volatility, geopolitical and political instability (the country is deeply divided politically) and more uncertainty as the year unfolds. If there is a market rally that is sustainable, it will not begin until the Fed stops QT and starts injecting liquidity into the financial markets and lowers interest rates, which may not take place until the second half of the year. We do not subscribe to the Goldilocks scenario unless all the factors listed above take place. To conclude, we feel the recession has been delayed but not avoided.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.